There, a better sense of the city came to me; from the walk down ‘wood street’, where store after store of carpenters peddled their wares, from door handles to entire fleets of furniture, to the filth and bilge in the paths and back alleys of Chinatown. Soon hungry, and going against all instincts otherwise, I sat at a noodle bar, squeezing onto a bench between shoppers and gossipers. The lack of any English on the menu only added to the flavour and, besides, the busy waitress (if that’s what she was) spoke it fluently, thrusting a festering selection of chilli oils in front of me before a bowl of noodles and an ice tea materialised. Dismissing any fears of the consequences of my lottery lunch, I tucked in, embracing what was surely the real essence of what coming to a Thai city must be about. Something I’d missed on my fleeting visit years before.

There, a better sense of the city came to me; from the walk down ‘wood street’, where store after store of carpenters peddled their wares, from door handles to entire fleets of furniture, to the filth and bilge in the paths and back alleys of Chinatown. Soon hungry, and going against all instincts otherwise, I sat at a noodle bar, squeezing onto a bench between shoppers and gossipers. The lack of any English on the menu only added to the flavour and, besides, the busy waitress (if that’s what she was) spoke it fluently, thrusting a festering selection of chilli oils in front of me before a bowl of noodles and an ice tea materialised. Dismissing any fears of the consequences of my lottery lunch, I tucked in, embracing what was surely the real essence of what coming to a Thai city must be about. Something I’d missed on my fleeting visit years before.

That afternoon, I walked and walked, seeking and soaking up all that the city centre’s streets had to offer, through hawkers and snack vendors, more and more market stalls than you could shake a dried fish at – some created in the most unlikely places; never mind back alleys, often pavements were converted such that you’d suddenly enter a narrow makeshift covered walkway – until, legs lumpen beneath me, I retreated to the hotel for a dip in the pool and a soothing massage in the sanctity of the spa.

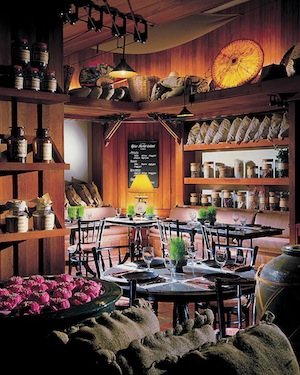

Having been out all day, when it came to dinner I settled for the comfort of the hotel. Strange as it may seem, a week in the country, sampling everything the cuisine had to offer, you’d think I’d have opted for something different. And there was certainly the choice. Five restaurants no less, and I was sorely tempted by the steakhouse. But I’d been told that Spice Market, the hotel’s 30-year old Thai restaurant, was one of the most popular and noted in the city, if not the country. I couldn’t pass it up.

Situated in one of the two open courtyards that adjoin the hotel, being the Thais’ favourite, it was no surprise it was full and my late entry had me placed in a corner but, being alone, ideal for people-watching. Evidently it was spice market by name and spice market by nature, for the decor was made up of artefacts relating to trade over the centuries, with earthenware jars, gunny sacks and maps of trade routes.

Sipping a Tang Mou aperitif created from Bangyikhan rum, watermelon, ginger and lime juice, I considered the menu. It was extensive. In sharp contrast to the gentle backwater pace of the Tented Camp and its set menu, here Four Seasons offers everything you’d anticipate from a dynamic, cosmopolitan city. This transfer from green to grey jungles threw me somewhat and I was dazzled not only by the choice of restaurants but the choices on the menu, sending the waiter back thrice undecided until I relented and asked for recommendations.

Sipping a Tang Mou aperitif created from Bangyikhan rum, watermelon, ginger and lime juice, I considered the menu. It was extensive. In sharp contrast to the gentle backwater pace of the Tented Camp and its set menu, here Four Seasons offers everything you’d anticipate from a dynamic, cosmopolitan city. This transfer from green to grey jungles threw me somewhat and I was dazzled not only by the choice of restaurants but the choices on the menu, sending the waiter back thrice undecided until I relented and asked for recommendations.

With many dishes I’d never seen in a Thai restaurant before, naturally it was these I ordered; deep-fried beetle fish with sweet and sour chilli sauce – like cod, white and fleshy, it’s less about flavour than texture and when the sauce was added this dish came alive (not literally, I should add), particularly enhanced with fried lime leaves and accompanied by peppery morning glory. Alongside this a crispy catfish salad with sweet pork and green mango sauce was nothing like what I was expecting; the light, fluffy batter it came in worked a treat with the sweet chewiness of the pork and the sour mango. With all the fish, I went straight in for the Colombard from Thailand’s Monsoon Valley, crisp and citrusy and a fine accompaniment to the spiciness. But perhaps the one dish that resonated, by both repelling and intriguing me at the same time, was the durian sundae. Durian, for those of you who don’t know it, is the fabled fruit in the Far East that locals devour, and smells not unlike rotting flesh. That it might be used to flavour an ice cream must surely test even the most adventurous of chefs. But, when in Rome and all that, order it I did, and as much as the aroma was hinted at it was unbelievable moreish. Though I fear that may be my first and only sampling of the fruit itself.

After such a blow-out, what I needed was to run it off. So, the next morning, foregoing the high tech cool of the hotel’s gym, I noted that Lumpini Park, the city’s main central green spot, was but a stone’s throw. Here, the only hint of the city was the distant hum of traffic and tower blocks poking above the tree-line. I set off, following a trail of other joggers around a central lake, at one point passing a bell tower pagoda tolling Big Ben’s chimes,  although not quite as accurate a timepiece. It was 11am and the clock read five past four. The more accurate time-keeping, however, came from a very curious incident I found as I trotted round the park’s central pathway. Among the other joggers, dog-walkers and daydreamers, suddenly a tinny cacophonous sound began to emanate across the park, and behind the clearly blown speakers it came from I could make out ceremonial music. People stopped in their tracks, bowed their heads solemnly and awaited its passing. I did likewise, fearing the consequences of moving, panting and catching furtive glimpses about me as I tried to discern quite what was going on. In a short while, it ceased and people carried on their way. Back at the hotel, I enquired as to the oddity that had just taken place. “Ah, that is the national anthem, sir, it plays twice a day in the park and people stop to pay their respects to the King.”

although not quite as accurate a timepiece. It was 11am and the clock read five past four. The more accurate time-keeping, however, came from a very curious incident I found as I trotted round the park’s central pathway. Among the other joggers, dog-walkers and daydreamers, suddenly a tinny cacophonous sound began to emanate across the park, and behind the clearly blown speakers it came from I could make out ceremonial music. People stopped in their tracks, bowed their heads solemnly and awaited its passing. I did likewise, fearing the consequences of moving, panting and catching furtive glimpses about me as I tried to discern quite what was going on. In a short while, it ceased and people carried on their way. Back at the hotel, I enquired as to the oddity that had just taken place. “Ah, that is the national anthem, sir, it plays twice a day in the park and people stop to pay their respects to the King.”

As alarming as a sprawling Asian city can be at first touch, one quickly adjusts and within a day I was positively embracing the cultural freedoms afforded me in Krung Thep. I was catching tuk-tuks like a native, negotiating terms with drivers and even, on one occasion, directing them when lost.

Having acclimatised, and feeling rather adept at getting around, I took another route round to the city centre the next day. This time, by river bus. As with any major city, its river is its lifeline and Krung Thep is no exception. The Chao Phraya is a thick, mucky, sweeping deluge of a river, criss-crossed by buses and taxis and foamed up by dozens of longtails skipping their way along its course. A short hop on the sky train from the hotel to the nearest harbour stop, my destination was the more historic side to the centre and one spot in particular.  This was Wat Pho, home of the ‘Reclining Buddha’. I’d missed it when I was last here and had regretted it. While the temple complex is intricate and maze-like, getting lost trying to find it is frustrating but it’s only more joyous when you come across this gargantuan golden figure, reclining in a manner that reminded me of a Roman Emperor. But far from being imperious, Buddha’s expression is soft and serene, in absolute calm and contentment. Well, he would be, it’s his last position as he passes into Nirvana. But more impressive than the gilding to his massive 150ft frame is his feet, the soles of which are minutely decorated with designs of mother-of-pearl. My haste to get there was soon dissipated into far more bucolic tranquility as I left, something evident in the Thais’ own disposition. Which is ironic when one considers what I was about to get into that evening.

This was Wat Pho, home of the ‘Reclining Buddha’. I’d missed it when I was last here and had regretted it. While the temple complex is intricate and maze-like, getting lost trying to find it is frustrating but it’s only more joyous when you come across this gargantuan golden figure, reclining in a manner that reminded me of a Roman Emperor. But far from being imperious, Buddha’s expression is soft and serene, in absolute calm and contentment. Well, he would be, it’s his last position as he passes into Nirvana. But more impressive than the gilding to his massive 150ft frame is his feet, the soles of which are minutely decorated with designs of mother-of-pearl. My haste to get there was soon dissipated into far more bucolic tranquility as I left, something evident in the Thais’ own disposition. Which is ironic when one considers what I was about to get into that evening.

I had one last date before my departure and in this I was instructed to catch a motorbike taxi to Soi Sukhumvit 3, the heart of Krung Thep’s nightlife. As with many things in Thailand, what we’d consider dangerous for health and safety gone mad, they take in their stride. 60mph in low evening light, weaving through traffic without a crash helmet. Let’s not be churlish, it was fine. But I needed a stiff drink at the other end and there, in a bar met by the man I’d visited years earlier, my old friend and now big shot producer in the Thai film and TV industry, I was instructed in our night out. It’s not what you think, Thailand’s somewhat salacious nocturnal reputation remained untouched, but he rattled off a succession of bars’ names. To choose? I asked. No, we’re going to them all, he said. And one stuck in my mind, from that trip ten years before. It was a 24 hour stopover at the time and, staying at his apartment, I asked after dinner, “What are we doing now?” “We’ll go to bed,” he said. Phew, I thought, I was knackered with jet-lag. I went to my room and hit the pillow. Ten minutes later he knocked on my door, dressed to the nines. “What are you doing?” he asked. “I’m in bed,” I remonstrated. “You idiot,” he retorted, “get up and get dressed, ‘Bed’ is a nightclub.” This rather summed up the Thais’ take on a night out. You can easily get a second wind.

Krung Thep is the embodiment of Thailand. It defines Thailand. From its majestic temples and palaces to its most humble shrines, from the exotic dining and luxurious hotels to the street vendors and markets, from the vibrant nightlife to the calming parks and pagodas, if you want to know anything about the country, its people, its city life, then this has to be your starting point. But then it most likely is, if you haven’t been already. It is, after all, what the Thais call their capital. But we know it by its more familiar name: Bangkok.