On the Monday of the trip, two and a half days in – the dead centre of the tour – we returned to the South Tyrolean capital of Bolzano. Located in the south of the province, Bolzano (or ‘Bozen’ in German) is sunk in a pot-like depression encircled by mountains. I was told that because of its situation, summers get hot and winters very cold. When we were there it was muggy and a little overbearing compared to the cool temperateness of the rest of the region. Culturally and architecturally it differed too from what I saw elsewhere. The buildings were a mixture of Gothic and Romanesque, of clean lines and ornamentation. When I wandered the streets on my first night I was struck at hearing German and Italian spoken in almost equal measure. The people too I found difficult to define either in face, form or fashion. Were these Germans I was looking at, or Italians?

“I am not Italian. I am not Austrian. I am South Tyrolean!” Proclaimed Messner early on in our visit.

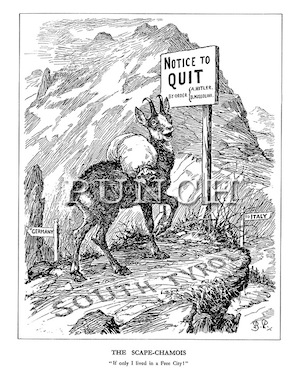

It was said with his typical bullishness but it also spoke of the unyielding assertiveness of a people whose land has been invaded and fought over countless times in the last two millennia. For the South Tyrol is border country, a crossroads place, whose profusion of castles speaks not of the picturesque, but of defence and submission. In its two thousand year history it has passed through the hands of the Romans, the Goths, the Lombards, been absorbed into the Holy Roman Empire and then into the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In 1920, following the end of the First World War, it was annexed by Italy. Although the southerly township of Bolzano had always been culturally homogenous, the rest of the region had been culturally and linguistically Germanic for centuries. (To an ignorant Englishman such as myself, Messner comes across superficially as a classic German type – blunt and a trifle humourless with a heavy accent and particular phrasing once so imitated by schoolboys.)

Under Mussolini’s fascist direction, the region underwent a programme of intensive ‘Italianization’. The German language was suppressed and Italian-speaking immigrants were shipped in. In a short cultural tour of the city, our guide – a retired German émigré architect – witheringly pointed out the severe Communist Block housing thrown up on the other side of the Adige River in the twenties and thirties. Although resistance and protest led to the region becoming semi-autonomous in the early seventies, and successfully so (the Dalai Lama has looked at it as a possible model for Tibet) and although I detected no cultural unease or resentment between the German and Italian parts during my visit, these are the troubled facts of the province’s history. As much as the rock and ice of the Villnöss Valley, the declamations of his father and the death of his brother, these are the elements which have been thrown together in the mix which has formed Reinhold Messner.

Under Mussolini’s fascist direction, the region underwent a programme of intensive ‘Italianization’. The German language was suppressed and Italian-speaking immigrants were shipped in. In a short cultural tour of the city, our guide – a retired German émigré architect – witheringly pointed out the severe Communist Block housing thrown up on the other side of the Adige River in the twenties and thirties. Although resistance and protest led to the region becoming semi-autonomous in the early seventies, and successfully so (the Dalai Lama has looked at it as a possible model for Tibet) and although I detected no cultural unease or resentment between the German and Italian parts during my visit, these are the troubled facts of the province’s history. As much as the rock and ice of the Villnöss Valley, the declamations of his father and the death of his brother, these are the elements which have been thrown together in the mix which has formed Reinhold Messner.

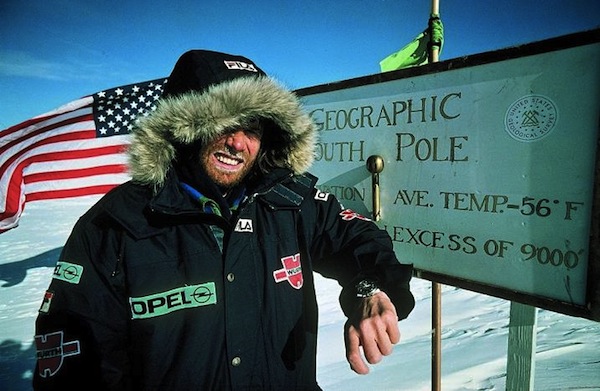

Messner didn’t exactly give up climbing after Lhotse, but he did give up climbing at his previous obsessive intensity. He continued making expeditions to the high places of the world, but with a different agenda. His real mountains though were now flat and wide – the polar wildernesses. Messner had moved from the vertical to the horizontal. In 1989-1990, with Arved Fuchs, they crossed Antarctica on foot, becoming the first men to reach the South Pole without animal or motorised aid. In 1993 he made a mammoth 2,200 kilometre trek across Greenland and in 2004, at the age of sixty, he fulfilled an old desire by crossing the equal immensity of the Gobi Desert in Mongolia.

Throughout this period he made regular excursions to the wild places of Asia, Africa and South America, exploring the myths of mountains and the recurring theme of the Holy Mountain. He even drew ridicule for seriously investigating the existence of the Himalayan Yeti, “The yeti story undermined him in elite alpine culture,” admitted Hans Kammerlander. Messner himself laughingly concluded that the fiercesome Yeti was the Himalayan Brown Bear.

Despite his retirement from professional climbing, there was one mountain that continued to exert a powerful psychological hold on him: Nanga Parbat. In 2000, on the thirtieth anniversary of Günther’s death, Messner returned to climb the mountain with a small expedition which included younger brother Hubert, “We decided to climb Nanga Parbat on a completely new route, a very beautiful route.” That route took them up the Diamir face and Messner pointed out the site of the tragedy. “We had perhaps all these strong feelings,” Hubert observed, “In the tent he was calling me every time ‘Günther’.”

A year later Messner was invited to attend a press conference hosted by the German Alpine Club at the launch of a new biography on Karl Maria Herrligkoffer. As one of the world’s leading alpinists and a former colleague of Herrligkoffer, Messner’s presence was obligatory. Besides, the dispute between the two men was an old one and any rancour was presumed to have faded. So it was with some astonishment amongst those in attendance that Messner used the occasion to publicly denounce the old expedition members.

Accusations flew back across the divide, including that Messner had been studying maps with a view to making a lone ascent, and most cruelly, that he had abandoned Günther to die. The old feud was resurrected, as fresh and jagged as ever. As before it was one man’s version against the group.

Four years later, in 2005, three Pakistani climbers stumbled upon the remains of a body in the Diamir Valley. The old style leather climbing boot indicated that it had been there for more than two decades. DNA tests confirmed the presence of the rare Messner genome. The body was discovered at 4,300 metres. With the annual movement of the glacier, it was exactly at the point it should have been had it been buried under the avalanche where Messner had always claimed. After thirty five years, they had found Günther.

“He always knew Günther was there.” Stated Uschi Demeter. If privately the discovery of the body confirmed what Messner had always known, then publicly he was exonerated. As with so many things, Messner was proved right.

On that last night in Bolzano we were invited to attend the preview of a new Messner biopic titled simply and grandly, “Messner”. The film was a documentary mixing original footage, contemporary interviews with family and colleagues and dramatic reconstructions of some of the key moments of his life. The film was in German, without subtitles, which sounds painful for a non-German speaker but it was surprising how easy it was to follow (reminding me of the view that a film might be stripped of sound but should still be understood). The greatest loss was not being able to understand what was said in the interviews, some of which were clearly very emotional. There were some beautiful aerial shots of mountains but perhaps the most memorable sequence was one from the 1970 Nanga Parbat expedition. Here was Messner and his brother in all their dazzling youth and ebullience, shock-headed and lithe and totally irrepressible. The bright grainy stock and roustabout fooling for the camera felt like an old ‘Monkees’ or ‘Beachboys’ video and made it instantly nostalgic. That the scenes were shot before the ascent and in ignorance of the tragedy that awaited made them hauntingly poignant.

On that last night in Bolzano we were invited to attend the preview of a new Messner biopic titled simply and grandly, “Messner”. The film was a documentary mixing original footage, contemporary interviews with family and colleagues and dramatic reconstructions of some of the key moments of his life. The film was in German, without subtitles, which sounds painful for a non-German speaker but it was surprising how easy it was to follow (reminding me of the view that a film might be stripped of sound but should still be understood). The greatest loss was not being able to understand what was said in the interviews, some of which were clearly very emotional. There were some beautiful aerial shots of mountains but perhaps the most memorable sequence was one from the 1970 Nanga Parbat expedition. Here was Messner and his brother in all their dazzling youth and ebullience, shock-headed and lithe and totally irrepressible. The bright grainy stock and roustabout fooling for the camera felt like an old ‘Monkees’ or ‘Beachboys’ video and made it instantly nostalgic. That the scenes were shot before the ascent and in ignorance of the tragedy that awaited made them hauntingly poignant.

There have been other films made about Messner. Perhaps the most artistically assured was Dark Glow of the Mountains made by Werner Herzog in 1984, a documentary about Messner and Hans Kammerlander’s double traverse of Gasherbrum II and Gasherbrum I. Less interesting for its sentimentality and subjectiveness was Joseph Vilsmaier’s dramatic rendering of the 1970 Nanga Parbat expedition titled simply, Nanga Parbat.

It is significant that given the rich dramatic and visual potential of mountain climbing, so few films have exploited it and of these, even fewer have been any good (Touching the Void is the only one that springs to mind and one that Messner himself mentioned in our conversation.) It was clear that Messner has more than a passing interest in film-making. Knowing that I was a film-maker he told me about a story he’d like to make involving his daring rescue of Peter Hillary – Sir Edmund’s son – and two companions in 1979 in Ama Dablam, Nepal.

Although he was polite about it, I got the sense that Messner himself was not altogether happy about his film. Clearly it was made with his sanction and co-operation, but therein may have lain some of the problems. It was essentially hagiography. Both film and director were clearly in awe of their subject. Apart from this it was rather conventional in its telling and the reconstructions a little hackneyed. I don’t know what particular gripes Messner had but he did have this to say about the process, “You need one head to make a film, not two.”

It was an astute observation but also a revealing one. Once he has finished with the museums and they are smoothly running themselves, is the next mountain in Messner’s sights that of film-maker? Making films is a young man’s game and as with climbing it takes years to master the skills. At sixty-eight it may be that Messner simply hasn’t the time left to take on this challenge. But then Messner has proved the naysayers wrong so many times it would be foolish to discount his ambitions. If anyone can, Messner can.