More than anything, the Messner I had observed was a shrewd businessman and self-publicist. ‘Mountain’ Messner may have baulked at the notion of spending five days in the company of a group of prying journalists, but ‘City’ Messner (for want of a better name) was canny enough to know the advantages. Despite his occasional flashes of irascibility (understandable given the circumstances, and in any case befitting a veteran of more than two thousand climbs) the trip was Messner’s idea.

Messner is undeniably a bright and educated man with great knowledge on many different branches of human experience; but he is also a man not given to inquiring on the opinions of others, “My übermensch is a self-determined person who would never accept something, some rules from high up.” The other consequence of this was that he had scant time for the ordinary. I never heard him ask another a question. He always seemed to have the answer at his fingertips.

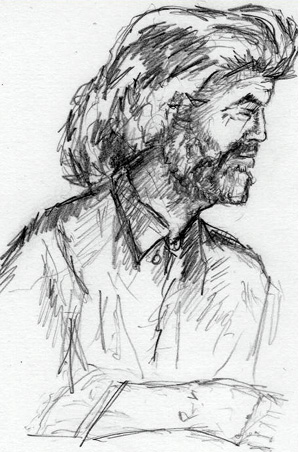

As the evening wore on I was struck by the absurdity of the position. Messner sat in the middle, the very compass centre from which all things radiated. Fittingly the wall was at his back, the great blocks of undressed stone blurring into the steely wire of his hair and beard, creeping into the furrowed lines of his brow and the great fan of wrinkles etched into his temples. Conversation turned from climbing and the events of his life to the very meaning of life. Messner the Mountaineer had become Messner the Sage and he was not shy of distributing his pearls amongst the assembled company. Much of what he had to say was fascinating and thought-provoking, born, as it was, out of a life of action and incident, but some, perhaps reflecting what I had perceived as the duality of his existence, came across as contradictory and fuzzy. As a recent father to a baby girl and as someone who enjoys adventure and physical risk, I was keen to understand how he dealt with the business of leaving family with the possibility that he might not return.

“My family, they need to know that I am there…does that answer your question?” He added somewhat tetchily. Clearly, not.

It may have been a language thing but I couldn’t help feeling that I had hit upon an uncomfortable area, an area that couldn’t be expressed in pithy eloquence. It was the same when I spoke to him of art, or rather the response I got was not the one I was expecting. The paintings in the museums revealed someone with a fine eye. I was expecting an art lover but instead I found a collector, someone who regularly flew to the big European auction houses – someone with nous and knowledge – but, I felt, no particular passion. That word again and the singular lack of it.

The night grew long in that close stone dining room. The voice and figure of Messner seemed to swell as those of the group receded. There was something undignified in the fauning and hanging on every word. Yes, this was an extraordinary opportunity and, yes, Messner’s achievements were extraordinary, heroic even, but Messner the man was flesh and blood, deeply flawed, like the rest of us. There is a separation and distinction between Messner’s achievements and his personality but just as it is easy to confuse an actor with the roles he plays, so too was Messner being muddled with his climbing masterpieces. I marvelled at how, in the twenty first century, we still seem to need gods and heroes, no matter the reality.

It was the last day of our adventure and fittingly we were visiting the fifth and final of the Messner museums – the MMM Ripa. The collection was housed in Bruneck Castle in the north east of the province, once the summer residence of the prince bishops. It was the grandest of the castles so far, as palatial as it was martial, with walls of sheer yellow stone enclosing panelled chambers once warmed by emblemed porcelain stoves. It was also the only castle of the group not set on a height, but merely on a moderate rise overlooking the nearby medieval town.

Some of the party were already leaving; the rest would go at different points during the course of the afternoon. I was one of the last to depart and would share a final supper with our host. There was much handshaking and the bittersweet feel of valediction hung in the air.

I set off to explore on my own. This last museum was dedicated to the peoples of the mountains, drawing on cultures represented in all six of the inhabited continents. I had stopped to read a couple of stanzas of the Herman Hesse poem, Steps, which was fixed to a post in a dim passageway, The heart must submit itself courageously to life’s call without a hint of grief.

An old lady approached and began talking to me. She was German, must have been eighty or more, but was in vigorously rude health. Her white hair was in a bun and her blue eyes glittered in the gloom. She looked the sort that would tramp the hills all day on nothing but an apple and fresh air, or ford a stream with a mewling calf in her arms. The last of an old breed. When she saw the look of confusion on my face she switched to flawless English.

“Reinhold Messner knows a lot about mountains – true – but his knowledge of these cultures is no more than as a tourist. He spent a few weeks with the Tibetans. He did not live with them. Where are the explanations here? Sir Edmund Hillary did so much for the people of Tibet. He built roads, schools and bridges. His name is known there and he is admired. Messner has done nothing for the local people. He is not known or liked. So look, but with a critical eye.”

It was a strange an unexpected encounter. I was aware that any public figure would have detractors and admirers, and of the former, their reasons would be multifarious and not always rational or objective (so too with the latter) but as I wandered the chambers and halls of the museum the sense grew in me that the objects, as interesting as they were individually, had been rather roughly chucked together. Despite the modern presentation, what I seemed to be looking at was old school Victorian collecting. What was lacking was depth.

On the drive to the station I showed Messner the sketches I had done of him during the course of the trip. He looked at them somewhat desultorily, weary perhaps from all the fuss. “What are you?” He asked. “An artist, writer or film maker?” Indeed, and a question I have asked of myself more than a few times. But then maybe the same question has been asked of Messner by friend and foe and possibly even by himself. What is he – Mountaineer? Mathematician? Philosopher? Writer? Adventurer? Anthropologist? Museum curator? Perhaps the answer was given, or rather not given, in that stone clad dining room in the clouds, the night before:

On the drive to the station I showed Messner the sketches I had done of him during the course of the trip. He looked at them somewhat desultorily, weary perhaps from all the fuss. “What are you?” He asked. “An artist, writer or film maker?” Indeed, and a question I have asked of myself more than a few times. But then maybe the same question has been asked of Messner by friend and foe and possibly even by himself. What is he – Mountaineer? Mathematician? Philosopher? Writer? Adventurer? Anthropologist? Museum curator? Perhaps the answer was given, or rather not given, in that stone clad dining room in the clouds, the night before:

“No-one will really know you by the end of your life, apart from your wife, and then not completely.”

Perhaps the beauty of Messner is that, finally, like the mountains themselves, he is unsolvable; a jagged enigma.