Culturally, our trip was vastly different, and in more ways than you can imagine. Switzerland has changed dramatically. Where now we might be thrown banknotes and ganache truffles by the townsfolk, in 1863 a tourist was advised to arm themselves with small coins to ward off the myriad of beggars and urchins swarming “like wasps”. With poverty rife, illness was commonplace, and much of that symptomatic of the restrictions of the mountains. In Sion, for example, in the Valais, Miss Jemima and her party encountered “many poor miserable cretins and goitres”, deformities endemic through an iodine-deficient diet blowing out the thyroid gland. Hard to imagine now, and considering the Valais is one of the wealthiest Alpine regions boasting resorts such as Verbier and Saas-Fee. We, by contrast, sampled the fine wines the region has to offer. And in Leukerbad, where they witnessed the infirm bathing in the thermal spas for hours on end, our dip was a leisurely one; the champagne breakfast served on trays being a novelty rather than a homeopathic necessity.

We may have been spared impoverishment, afforded a change of clothes and given ease of passage for the most part but, culturally, our hosts strived for authenticity. Never more so than in the culinary offerings and at every lodging we were treated to a ‘traditional Swiss meal’. A novelty at first, by the close of the trip, I was struggling to enthuse over meat and potatoes on the 17th occasion, though grateful to be spared the “watery soup” and mountain trout that “had exchanged its natural element for one of oil” of Miss Jemima’s day.

It’s no understatement that the development of the railways has dramatically altered Switzerland’s fortunes, turning previously cut-off villages into bustling skiing resorts; the beautiful Grindelwald, for one, with its wooden chalets dotted about the foothills like cows in pasture, framed by the majesty of the Eiger, the Munch and the Jungfrau, the scale of the distant dwellings putting their sheer enormity into perspective. It, too, coincidentally, prompting another British-begun activity, that of downhill skiing – but that’s another story.

But, more than the established resorts, which have developed with the influx of tourism, we passed through those lesser-known and which might otherwise have been missed were we not following in Jemima’s footsteps. The charming Kandersteg has seen its fortunes rise, and fall, with the coming, and subsequent going, of a railway. It is, nevertheless, a beautiful village, nestled in a lush green valley with a roaring meltwater river coursing through it, and cradled in dramatic scenery.

Apart from the many social changes in the last 150 years, we benefited from many physically that would not have been possible in Jemima’s day. Such was the demand for railways to accommodate tourists since their trip that the most extraordinary engineering feats have been undertaken in the most unlikely of places. Most strikingly, the train through the Eiger. Commissioned in 1896, the line ascended to what is still the highest train station in Europe, the Jungfraujoch. If Rigi seemed spectacular, the sights greeting us above the clouds at the observatory perched just metres from the summit were a joy to behold.

Of the entire tour there was, thankfully, one aspect of the country that has remained substantially unchanged; the mountains themselves. We might not have climbed the Gemmi Pass but the sight from the top, looking back down onto Leukerbad is, simply, breath-taking. And the waterfalls. My word, the falls. The beauty of mountains is that while you can ascend, things also come down, namely water. As we descended from Jungfrau we had the most spectacular view of the Lauterbrunnen valley, with the wispy Staubach falls, billowing like delicate lace falling from the sky.

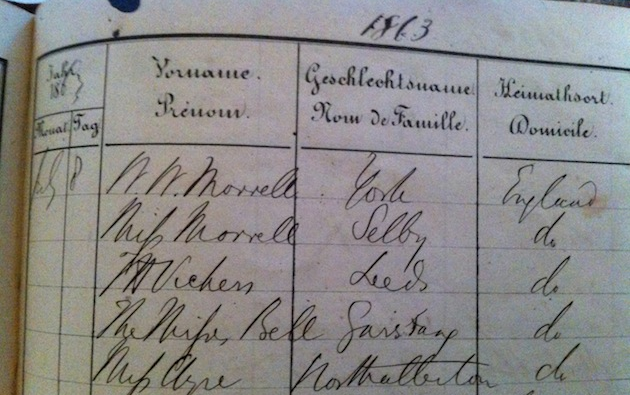

For the final ascent, we took Europe’s first cogwheel mountain train – yet another innovation – built in 1891 to accommodate the now thousands ascending the peak and filling the Rigi Kulm hotel. Standing as it did in its heyday the hotel rivalled Europe’s finest before it, too, succumbed to decline after the First World War. Our modern incarnation, however, reminded me more of The Shining, we being the only guests; an image compounded by the sudden inclement weather that befell us. Not in the least dispirited, nor fearful, we retired in good time, braced for the 5am wake-up call by alphorn. One thing did greet us here, however, that was the most tangible grasp of the century and a half spanning these two trips. In the hotel’s guestbook, having survived fire (of course) and demolition, we saw the signatures of our intrepid predecessors.

At the appointed hour, I flung the curtains open to be met by a wall of fog. Driven by the hope the sun might clear it, I went outside, delighted to find nearly all of our party there at the summit. In the end, it didn’t matter that we hadn’t seen the sunrise – that might even have been an anticlimax – it was the culmination of an extraordinary adventure. And, besides, I could experience it vicariously, for, 150 years earlier, Miss Jemima and her party witnessed that “the vastness of that mighty panorama was impressively sublime and in hushed silence we gazed on that serrated belt as daylight awoke on its three hundred miles of mountains, valleys, lakes and villages.”

And, as Diccon mentions in his book, Miss Jemima’s view of a Rigi sunrise has scarcely changed at all.

Diccon Bewes’s Slow Train to Switzerland is available now from Amazon here and from all good bookshops.