First Larry went to Liverpool, Britain’s ‘second’ city and home of its mercantile heritage. Now, Harry Chapman visits Newcastle, the gateway to the north east and cornerstone of the country’s industrial past…

“You look like you’ve come from somewhere exotic!” exclaimed the pretty, brown-eyed girl at the hotel reception. I was wearing my olive green Tyrolean hunting jacket, straw trilby and vintage Swedish drill boots. I was in Newcastle to cover, amongst other things, Newcastle Fashion Week, and had thrown on some glad rags to show I was somehow qualified for the task.

“Only London,” I murmured deprecatingly.

“That’s exotic compared to Newcastle!” she laughed.

I was nineteen when I was last in the city. That was in the pre-Cheryl days, pre-Gazza even (which dates me cruelly). Back then it was the land of Newcastle Brown Ale, of a dying shipbuilding industry and a thriving football team and, to my closeted and fanciful schoolboy mind (which I was then), a place where surly ruffians would set upon you for merely asking the time, and whose verbal response, if ever given, would be unfathomable anyway. It also had a fine university to which several of my older friends at school had gone to and it was to attend one of their birthdays that I had, with curiosity and trepidation, travelled to the place.

I don’t remember much of the visit. It was late in the year during that depressing bridge between autumn and winter and before the enlivening boost of Christmas. It was very grey, very cold and very wet. I recall looking at these older friends with a trace of wonder, who had so confidently and dextrously embraced student rambunctiousness. My only distinct memory was of an old man of more than sixty, with a hobble but with the barn door shoulders of a retired docker, refusing to budge for a car which had mounted the pavement and was attempting to shoulder him out of the way to get to a petrol station. The stand-off seemed to last for years and was punctuated by roars of defiance from the old man. It reminded me of a Doctor Seuss cartoon where two typically Seuss-like creatures meet head-on on a path in a forest and each stubbornly refuses to move to let the other pass. In the meantime, the years roll by, the wood is cut down, a city springs up and the two creatures are left arguing on a tiny island in the middle of a spaghetti junction. The dénouement wasn’t quite as extreme here. I think the old man triumphed and the car backed down.

A rather skewed image to bear down through the years of the unreconstructed Geordie male, I’ll grant. I am aware that since the near total collapse of industry in the north in the nineteen eighties, the great northern cities have been undergoing vast change and renewal. Various “European City of Culture” awards have been given (Glasgow in 1990 and Liverpool in 2008). The phoenix has determinedly risen from the ashes. I myself have lived in Leeds for a year, have worked in Sheffield and have visited Liverpool and Manchester. I found them all (Leeds particularly) bright, sparky and energetic. It is no secret exactly. The one city I didn’t really know was Newcastle, and perhaps partly because of this, it was the one I was most drawn to see.

Having only ever travelled to Newcastle by train I can’t comment on the approach by road. Biased and perhaps ignorant as I am though, I would opt for train every time. It is an often dramatic, sometimes spectacular journey, especially in the latter stages. After the yellow sandstone elegance of York, one passes by the spires and citadel of Durham, before running along the coast with the gunmetal disc of the north sea stretched out to the east like liquid quicksilver, easing the eye from the brilliance of the green turf of the surrounding land. Whereas the ride into London, from any direction, is a slow crawl through suburbia and semi-industrialism, Newcastle makes its appearance suddenly and dramatically. The Tyne valley drops away from the crest of the hill and you are hurtled across the shining waters of the river via the lattice steel spans of the Kind Edward VII Bridge, one of seven that link Newcastle and Gateshead across the River Tyne.

Propelled across a viaduct with urban canyons falling away on either side, spiked by lines of outstretched chimney pots, one soon finds oneself entering the maw of Newcastle Railway Station. Whilst it might lack the industrial grandeur of a Paddington or a St Pancras with their hanger-like bays and trellising of intricate ironmongery, it makes up for this in sheer elegance and simplicity of design. And here lies the irony. For a city so closely associated with the boom of industrialisation, with coal and iron, its principal railway station is a paean to self-restraint and classicism. Arches hewn from the light local stone run the length, above three of which are circular reliefs of Victoria, Albert and Edward VII. Enormous bronze doors, suitable for the Bank of England, sit in niches at the entrance like resting golems. Neither was this classicism of the station a façade or foil but continued deep into town, as I was to discover (or rather the station was a culmination of it.) To my surprise I was to find that Newcastle is a sublimely beautiful place.

Our home for the weekend (“we” being the addition of wife and child) was to be the exotically named Malmaison Hotel (wherein the young receptionist made her own charming pronouncement on the “exoticism” of Newcastle.) Like many places which are self-consciously named, the Malmaison wasn’t particularly exotic, nor, with the other implication of its name, was it particularly French. In fact it is the curiously chosen name for a chain of hotels scattered across the main urban centres of the UK with aspirations to the boutique. There was a lot of grey in the Malmaison, as well as purple, and black. The grey tended to be the soft brush of velour fabric, the black, hard tiles and the purple many things in between. (Our suite was an exception being grey velour sofas on grey carpet within grey walls – giving it an odd urban camouflage effect.) It was a style that might be termed “Corporate Boutique” or designed perhaps by footballers’ wives (Third Division, I’m afraid.)

Where the Malmaison perhaps faltered in style, it made up for in location. It is situated on the banks of the Tyne in the old industrial quarter which, like London’s Southbank before it, has been cleaned up and rejuvenated and is now a fashionable promenade strewn with cafés, restaurants and bristling with amblers. Almost directly opposite, on the other side of the river, is the immense red and yellow brick form of the Baltic Flour Mill, as iconic and beautifully ugly for Newcastle as Battersea Power Station is for London. Unlike the latter whose fate has been sealed, I believe, by conversion into luxury flats, the Baltic (whose unusual name was chosen after the original owners decided to name each of their mills after different seas of the world) has, since 2002, been a contemporary art gallery (or “centre”), much like the Tate Modern in the capital.  Linking the two sides at this point is the Gateshead Millennium Bridge, a pedestrian and cyclist’s bridge with the elegant curve of a harp and the feel of a musical note. It was the first so-called “tilting bridge” in the world (sometimes referred to as the “Blinking” or “Winking Eye” Bridge), the footbridge swinging up to meet the arch several times a day.

Linking the two sides at this point is the Gateshead Millennium Bridge, a pedestrian and cyclist’s bridge with the elegant curve of a harp and the feel of a musical note. It was the first so-called “tilting bridge” in the world (sometimes referred to as the “Blinking” or “Winking Eye” Bridge), the footbridge swinging up to meet the arch several times a day.

Whilst the bowels and organs of the Malmaison are of questionable taste, the exterior has an interesting heritage. Built by the Co-operative Society at the turn of the last century as a warehouse, it was one of the first buildings in the country to be constructed entirely out of concrete. It is sad that the architects didn’t think further on how the interior could be incorporated into the new guise of a hotel, and like the old Arsenal Stadium and countless other ‘heritage re-developments’, simply ripped the guts out.

Newcastle is a dream for walkers. It is small and relatively compact and whilst it unspools across a high and very steep hill, it is precisely this hill with its particular geological features which serves the architecture so well. Everywhere one turns there is a dramatic snapshot of stone-clad plunging street, bisected in the distance by one of the many bridges, with the gleaming fish scales of the river below and the gun metal grey sky above. The nearer one gets to the water and the steeper the hill, the more dramatic the vistas. Buildings soar above you as they climb the ascent, frozen in labour like carapaced caterpillars, narrow and bristling. Bridges shanked with riveted plates, criss-cross the horizon, losing weight and substance as they recede to the distant shore. It is a dizzying, dazzling spectacle reminiscent of the cross-hatched “carcerie” of Piranesi. In fact, what Newcastle reminds me of is not the gentle conservative evolution of other British cities but the savage upthrust of nineteenth century New York as classicism gave way to rampant capitalism and “progress” and the new century dawned tall and vigorous.  It has the same collision, with its elegance of stone and the fire-forged new materials of iron and steel embraced in the monolithic – in its case in its bridges which are vast and overawing. It is a reminder that the city was not only a hub of the Industrial Revolution but one of its major innovators – Stephenson’s “Rocket “, Joseph Swan’s electric light bulb and Charles Parson’s steam turbine all had their births here. Oddly enough but perhaps to complete the American allusion with a west coast loop, the other city Newcastle reminded me of was San Francisco, with its famously steep inclines and with its even more famous bridge – the Golden Gate (although admittedly this was on a far far grander scale than it Newcatle forebears; neither does San Francisco’s grid street system resemble Newcastle’s medieval layout.)

It has the same collision, with its elegance of stone and the fire-forged new materials of iron and steel embraced in the monolithic – in its case in its bridges which are vast and overawing. It is a reminder that the city was not only a hub of the Industrial Revolution but one of its major innovators – Stephenson’s “Rocket “, Joseph Swan’s electric light bulb and Charles Parson’s steam turbine all had their births here. Oddly enough but perhaps to complete the American allusion with a west coast loop, the other city Newcastle reminded me of was San Francisco, with its famously steep inclines and with its even more famous bridge – the Golden Gate (although admittedly this was on a far far grander scale than it Newcatle forebears; neither does San Francisco’s grid street system resemble Newcastle’s medieval layout.)

My exploration of Newcastle really began the next day. At eleven a.m. I met my guide, Gwen Keating, beneath the towering pinnacle of Grey’s Monument in Grainger Town, the historic heart of Newcastle. Gwen was a white haired lady with a determined, practical manner and a superb knowledge of the history of the city. Not only was she able to recount full histories of all the major streets and buildings, but also the more modest backwater ones as well. All this was enlivened by stories, unusual facts and an engaging manner. (One American visitor, on seeing the medieval castle, was said to have exclaimed, “But why did they build the castle so close to the railway viaduct?”) Born and bred in the area, Gwen was clearly in love with her city. Like the best teachers, her passion was infectious.

It was fitting that the tour should begin under Grey’s Monument. Standing atop the fluted column, which is remarkably similar to Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square (and indeed both crowning figures were chiselled by sculptor Edward Hodges Bailey), stands Charles Grey, 2nd Early Grey. A local lad, whose family had their seat in nearby Howick Hall, Grey went onto become one of the ablest politicians of the era, capping his achievements with a stint as Whig prime minister between 1830 and 1834 and steering through the Reform Act of 1832 which saw, amongst other things, the abolition of slavery throughout the British Empire. To the eternal gratitude of many others (myself included) Grey is also credited with the creation of “Earl Grey Tea”. According to Twinings legend a grateful Chinese mandarin whose son was rescued from drowning by one of Grey’s men, presented a blend of tea scented with bergamot oil to Grey as thanks in 1803. (Grey family legend, a little prosaic, which is why the story has not taken hold, was that the tea was so blended to suit the water at Howick Hall, the bergamot used to offset the preponderance of lime in the local water.)

It was fitting that the tour should begin under Grey’s Monument. Standing atop the fluted column, which is remarkably similar to Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square (and indeed both crowning figures were chiselled by sculptor Edward Hodges Bailey), stands Charles Grey, 2nd Early Grey. A local lad, whose family had their seat in nearby Howick Hall, Grey went onto become one of the ablest politicians of the era, capping his achievements with a stint as Whig prime minister between 1830 and 1834 and steering through the Reform Act of 1832 which saw, amongst other things, the abolition of slavery throughout the British Empire. To the eternal gratitude of many others (myself included) Grey is also credited with the creation of “Earl Grey Tea”. According to Twinings legend a grateful Chinese mandarin whose son was rescued from drowning by one of Grey’s men, presented a blend of tea scented with bergamot oil to Grey as thanks in 1803. (Grey family legend, a little prosaic, which is why the story has not taken hold, was that the tea was so blended to suit the water at Howick Hall, the bergamot used to offset the preponderance of lime in the local water.)

The 2nd Earl Grey, Newcastle’s one and only prime minister, also lends his name to Grey Street, the sublime neo-classical fronted avenue which sweeps down from Grey’s Monument to the valley of the River Tyne. The architectural scholar Nikolaus Pevsner has described this street as one of the finest in England. To the uninformed visitor such as myself, expecting to find soot blackened warehouses and plain functional dwellings of red brick, it is one of the thrilling surprises of entering central Newcastle to discover instead a well preserved neo-classical gem. In fact, between 1830 and 1840 (during some of Grey’s tenure as prime minister) the whole of the city centre was re-built by builder Richard Grainger and architect John Dobson in the neo-classical style, the soft yellow stone quarried over the river in Gateshead. What we now see as “modern” Newcastle dates from this period. Of course in the rush to modernise and beautify much of the old was swept away. The dirty food markets lining the site of Grey Street were cleared and the river which bounded along below the cobbles flushing away the refuse, was neatly culverted.

Before strolling down Grey Street we had a wander through a couple of the old arcades at the top of the hill. The first, known simply as “Central Arcade”, reminded me, in the intricacy of the detail and the yellow and reddy brown tones, of Leadenhall Market in London. Built in 1906 on the site of the old Central Exchange (also a Grainger build) which was later ravaged by fire, it is embossed, floor to ceiling, with incredible art nouveau tiles (insured to the tune of one million pounds I was told) and was absolutely stunning. The other, known as a “Penny Arcade”, was much more modest in appearance but, with its plain tiling, was still possessed of a simple elegance. It was here that the “ordinary folk” of Newcastle could once wander and hope to pick up bargains for no more than a penny – everything from foodstuffs to haberdashery. Whilst the prices since may have taken a bit of a hike, it was extraordinary to think that this spare elegant market was the equivalent to the tawdry high street pound shop of today.

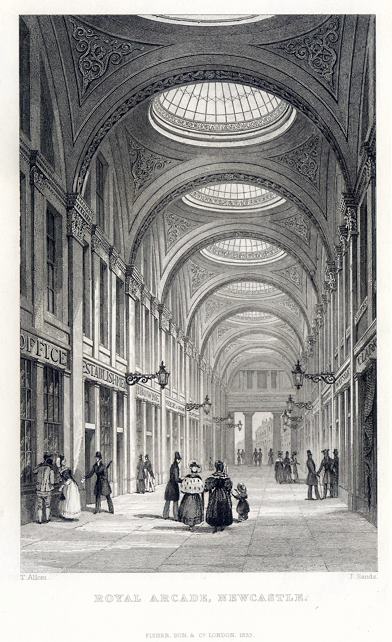

There was one arcade we were not able to visit. The Royal Arcade was another of Grainger and Dobson’s masterpieces. Built also in the 1830s it included along its length, shops, offices, banks, a post office and a “steam vapour bath”. I have seen photographs and etchings and can confirm that it was a truly gorgeous creation with a series of leaded cupolas running overhead, spilling soft light on the galleried windows and walkway below. All this is gone, demolished in the 1960s by the local authority who were gripped by a sort of Maoist zeal. It is frightening to think that in this decade, a bad time for Newcastle economically, the whole of Grainger Town was under threat by the developers’ wrecking ball. In the end much of it was spared although it wasn’t until the 1990s that a committed project for urban regeneration began to reverse the process of decline and fall. As well as the Royal Arcade the victims included the famous Nelson Street Music Hall, another Grainger gem, where Dickens read excerpts of his works (the façade still stands) and large chunks of the old Eldon Square which made way for the Eldon Square Mall – at the time of opening in Jubilee Year 1977, the largest indoor shopping mall in Britain.

There was one arcade we were not able to visit. The Royal Arcade was another of Grainger and Dobson’s masterpieces. Built also in the 1830s it included along its length, shops, offices, banks, a post office and a “steam vapour bath”. I have seen photographs and etchings and can confirm that it was a truly gorgeous creation with a series of leaded cupolas running overhead, spilling soft light on the galleried windows and walkway below. All this is gone, demolished in the 1960s by the local authority who were gripped by a sort of Maoist zeal. It is frightening to think that in this decade, a bad time for Newcastle economically, the whole of Grainger Town was under threat by the developers’ wrecking ball. In the end much of it was spared although it wasn’t until the 1990s that a committed project for urban regeneration began to reverse the process of decline and fall. As well as the Royal Arcade the victims included the famous Nelson Street Music Hall, another Grainger gem, where Dickens read excerpts of his works (the façade still stands) and large chunks of the old Eldon Square which made way for the Eldon Square Mall – at the time of opening in Jubilee Year 1977, the largest indoor shopping mall in Britain.

Sitting on the remains of the old Royal Arcade is “Swan House”, as brutalist a piece of architecture as could be conjured in the old Kremlin, as ferociously ugly as the arcade was beautiful. It reminded me of the multi-storey car park that Michael Caine’s Carter so casually hurls a businessman off in Get Carter (of course set and filmed mainly in Newcastle.)

There is though a pleasing end-note to all this cultural rape and destruction. T. Dan Smith, the most prominent politician in the city during the 1960s, who oversaw the plans to demolish Grainger Town, was later exposed as having used public contracts to advantage himself and various interests, was tried and jailed. In fact, it was the fog of civic corruption that was used to such authentic effect in Get Carter, a film that came out in 1971.

But it is not only early Victoriana that has suffered on the road of “progress”, because, of course Grainger and Dobson, to construct their classical dream, had to rip down what stood before them. Not much remains of medieval Newcastle although curiously enough, like the city of London after the Great Fire, which to Wren’s bemusement was rebuilt along most of the familiar old ratty lines, much of the current street layout of Newcastle follows the same medieval course. “Chare” is the Newcastle term for the narrow medieval alley which still exist is some profusion, especially around the riverside. (Interestingly, in Newcastle’s own “Great Fire” of 1854, many of the old chares immolated were not rebuilt as the surrounding houses had become slums and foetid breeding grounds for typhus and cholera.)

The oldest medieval building in Newcastle and in fact the oldest structure in the city is the castle from which the place derives its name. Nothing now exists of the original “new castle” which William the Conqueror’s eldest son Robert Curthose chucked up in haste to defend the kingdom against the Scots. The current existing castle is a stone replacement built a hundred years after the original motte-and-bailey went up in 1080. Confusingly, although “new” by chronological standards, this was not the castle from which the city derives its name. That was the “old” one constructed by Curthose, which was “new” at the time, if that makes sense.

The “new” or “newer” castle (depending on which way you look at it), a squat rectangular keep, seems curiously small and lost beside the brick railway viaduct that runs alongside it and the more modern buildings which have sprouted around it – a purposeless old relic from a forgotten age. It is only when one is standing directly under its walls that one appreciates its capacity to overawe and it superb martial design – the attacker (in this case me) is open to onslaught from a myriad guarded loops and positions.

The “new” or “newer” castle (depending on which way you look at it), a squat rectangular keep, seems curiously small and lost beside the brick railway viaduct that runs alongside it and the more modern buildings which have sprouted around it – a purposeless old relic from a forgotten age. It is only when one is standing directly under its walls that one appreciates its capacity to overawe and it superb martial design – the attacker (in this case me) is open to onslaught from a myriad guarded loops and positions.

The only other part of the castle remaining is the gatehouse, built after the last keep in the middle thirteenth century and now known with sinister implication as “the Black Gate”. Next to this, within where the bailey would have lain, are two open stone pits, the dungeons where prisoners would have literally been thrown.

Remaining within medieval Newcastle we returned to the river via the original postern gate and several flights of steep stone steps. Like London it is the river which gave Newcastle life and prosperity, where in the Middle Ages the wool trade flourished and later the trade in coal and shipbuilding. But it was the Romans who first recognised the strategic nature of the place and indeed who built the first bridge, the “Pons Aelius” (literally the “Bridge of Aelius” – Aelius being the family name of the Emperor Hadrian of “wall” fame of which this new settlement became one of the wall forts of.)

Whilst there’s no denying the beauty and elegance of Newcastle’s neo-classical city centre, for me what really defines the city visually are the plethora of constructions that span its river – the bridges. The Roman one – the actual Pons Aelius – was said to have lasted a thousand years. The medieval bridge that took its place held shops and houses much like the Ponto Vecchio in Florence or the old London Bridge. It was washed away in a flood and was replaced by a Georgian affair which was in turn demolished by the local arms manufacturer and ship builder William Armstrong who constructed the Swing Bridge (whose horizontal rotating mechanism was adapted from Armstrong’s own canon mounts) in 1876, to allow access for the fitting of his warships.

Further up is the elegant High Level Bridge. Designed by Robert Stephenson (George “The Father of Railways” Stephenson’s son) this intriguing structure was the first “double-level” bridge in the world with rail on the upper level and road traffic (horse driven in those days) on the lower. With the increase in type and weight of traffic the bridge has taken a hammering. Extensively repaired in the last decade it now only takes road traffic (but no rail) in a southbound direction.

Further up is the elegant High Level Bridge. Designed by Robert Stephenson (George “The Father of Railways” Stephenson’s son) this intriguing structure was the first “double-level” bridge in the world with rail on the upper level and road traffic (horse driven in those days) on the lower. With the increase in type and weight of traffic the bridge has taken a hammering. Extensively repaired in the last decade it now only takes road traffic (but no rail) in a southbound direction.

The bridge that has come to symbolise Newcastle and Tyneside is undoubtedly the towered iron arch of the Tyne Bridge. If the graceful silhouette is more than a little familiar it is hardly surprising. The Middlesborough firm of Dormon, Long and Co who built it also constructed the later iconic Sydney Harbour Bridge which it strongly resembles.

Harry’s exploration of Newcastle continues, where he moves from its past and is thrust into the city’s contemporary culture, with Fashion Week. Read Part Two…