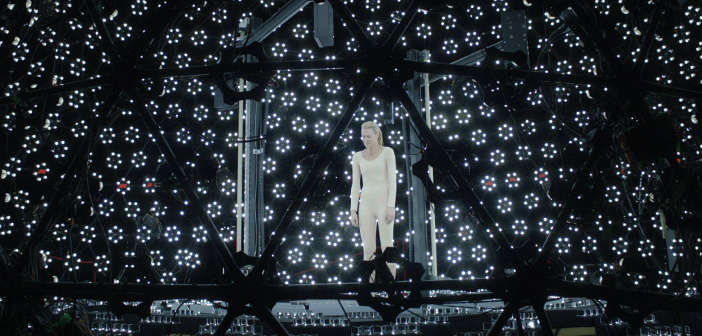

Ari Folman follows up his extraordinary feature-length animated documentary, 2008’s Waltz with Bashir, with this breathtakingly ambitious science fiction yarn. Robin Wright plays a version of herself, a 40-something actress drifting towards obsolescence thanks, as her battle-worn agent (Harvey Keitel) never tires of reminding her, to her terrible choices and a deep-seated fear of failure. Her studio, Miramount, given rather offensive voice by the excellent Danny Huston, makes her an offer of one last contract: they will ‘scan’ every aspect of her – physical body, gestures and mannerisms, voice, emotional responses – and henceforth own the IP that is Robin Wright. The actress herself must then retire and the studio will be free to recreate her younger self digitally in whichever films they choose (respecting the ‘no porn’ clause inserted in her contract, of course).

That represents one half of the film’s concept – so far, so good. The exploration of these issues is beautifully handled, with Wright wrestling between her need to provide for her seriously ill son, and the reluctant surrender of her artistic integrity as a performer. The scanning sequence itself is intensely moving, with Keitel emptying all the skeletons from the closet of his and Wright’s relationship in order to illicit the emotions required by the studio. Wright’s tough, glacial exterior slowly melts and then comes crashing down, defeated.

The film then shifts into its second phase, loosely inspired by Solaris author Stanislaw Lem’s 1971 novel, The Futurological Congress. An older Robin Wright attends the Futurological Congress, Miramount’s glitzy event to showcase its new technology, which dictates the visual aesthetic for the rest of the film. In Miramount’s ‘restricted animated zone’, everyone must take drugs that cause them to hallucinate intensively, so that they perceive the world as a kind of animated playground, in which they can transform into whichever avatar or form they desire. This sense of self is projected outwards and perceived by everyone else, resulting in a kind of constantly-changing Yellow Submarine environment, in which everything is bright, nothing is real and the eyes fundamentally can’t be trusted.

The rest of the film plays out against this backdrop, with Robin Wright dealing with the catastrophic consequences of such a dramatic sociological shift, all the while trying to keep hold of the motives which caused her to surrender her identity in the first place. If this is reading like the film is remarkably difficult to describe, well, that’s because it is. Waltz with Bashir made such clever use of its animated premise to explore the idea of the unreliability of memory, and although it’s fairly unconventional to entirely animate a documentary about a Middle Eastern massacre, that film did ultimately cohere as a concept. My reservation with The Congress is that it feels a little like a piece is missing: there’s this idea of actors selling their souls to be scanned digitally and exploited by studios, and there’s this other idea of an animated dystopian future where mind-altering substances have torpedoed any semblance of a rational society. What’s not clear to me is how or why we go from one to the other in the space of the same film.

Within the film’s various sections, there are some extraordinary moments. The scanning scene mentioned earlier is absolutely heartbreaking stuff from Harvey Keitel and Robin Wright; there’s a superbly drawn cameo in the animated zone which punctuated the confusion in the cinema with some real laughs; and the support from the likes of Danny Huston, and Paul Giamatti as the world-weary doctor, is excellent. The animation itself is wildly inventive and visually stunning, and Max Richter’s uneasy score provides the perfect accompaniment to the slow, relentless chaos on screen. Wright herself is outstanding, bringing clarity and fragility to a character that’s led mainly by her voice as the film wears on, and events become harder to follow.

The film ultimately left me feeling much as I did after watching the Wachowskis’ take on Cloud Atlas. I can’t honestly say The Congress succeeded as a coherent whole: even though the narrative only follows one main character in this instance, the leaps seemed too big and there wasn’t quite enough infrastructure present in the world-building to hold it all together (who pays for everyone to live like this? Why is everyone allowed to just be tripping balls all day?!) But if you’re going to fail, then fail like this – with staggering ambition and a vision that’s just too grand for one film to contain.

When Warner Brothers started pushing Man of Steel they trailed it as a product of the mind of ‘the visionary director of 300 and Watchmen’ – a line which brought a lot of laughs as the trailer popped up before various films throughout 2012 and 2013. Ignoring the fact they conveniently ignored the appalling Sucker Punch, it’s hard to see how Zack Snyder’s commitment to slow-mo, shouty men and tight costumes counts as ‘visionary’. Ari Folman, on recent form, certainly is a visionary – I just couldn’t quite keep up with him as we went through it. All that said, this is without a doubt one of the most interesting, creative and moving films I’ve seen this year and it deserves to be seen by the widest possible audience, particularly while it’s still on the big screen.

The Congress is currently showing in selected cinemas across the UK.