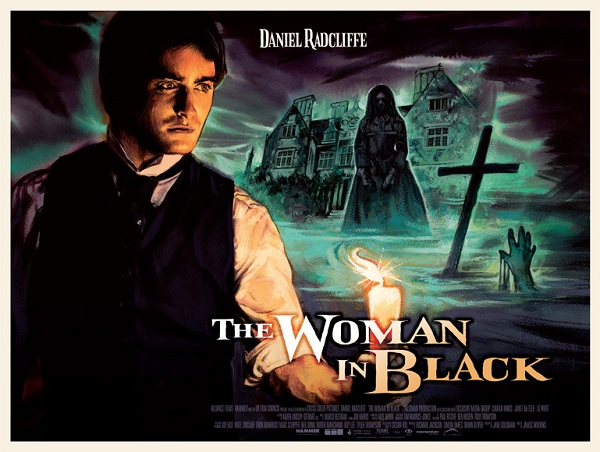

Daniel Radcliffe bears the weight of The Woman in Black almost solely on his shoulders. Despite being a recent alumnus of Hogwarts, it’s perhaps too large a burden. The central portion of the film has Radcliffe (as lawyer Arthur Kipps) alone in a dilapidated house of hell. There is little he can do but observe and react. When he’s required to interact with the formidable supporting cast his weaknesses are more apparent. Not least that he looks just a smidgen too young to be a recently bereaved father and a trained lawyer.

Dispatched to settle the affairs of a recently deceased woman, Kipps arrives in a quaint but markedly rude village in the heart of the Victorian countryside. Under the chocolate-box veneer, dark undercurrents flow. No one wants to talk, Kipps is warned to stay away and the children live confined to their homes.

A high rate of infant mortality stalks the frightened streets and hushed voices speak of a vengeful evil connected to the property of the dead woman. An apparition of a black-clad woman is said to lead youngsters away to their death. Nearby an abandoned house casts a deathly shadow over the place. The house lies across a narrow, sodden causeway precariously crossing the marsh. The path is covered by the tide for several hours a day, effectively trapping visitors there should they visit at the wrong time.

The only friendly face in the village belongs to Daily (a sombre Ciaran Hinds), a father grieving the loss of his boy. Daily drives Kipps across the marsh to the house but doesn’t hold with any of this “superstition nonsense”. As a lone voice of reason and science in the village, he is severely outnumbered.

Writer Jane Goldman has treated the original novel by Susan Hill as a template, changing a lot of locations and situations while maintaining the bones of the plot and the sense of dread. The Woman in Black is most effective when Kipps is sorting through the abundance of paperwork in the house. In his search he starts to hear noises, see things in his periphery. Something is with him. Tension is carefully built as he investigates. Shapes and noises move around him, elusively. One sequence calls to mind 1963 film The Haunting. A reverberating, bassy thumping emanates from behind a locked door. Even the house itself could be a long lost twin of Hill House from that film.

Director James Watkins (director of “Broken Britain” parable Eden Lake and writer of the curious My Little Eye) paces the scares in well-timed ebbs and flows maintaining a strong sense of foreboding. An accomplished cast brings a touch of class to a tale with little ambition beyond creep under the skin of the audience. A few well-worn tropes serve to distance the seasoned film viewer: wind-up toys springing to clock-sprung life of their own accord; glassy-eyed,  over-made-up, Victorian dolls observing all; and words etched in blood spewed across the walls. There is a small nod to the debate about the supernatural versus enlightenment but it is soon abandoned when the source of the terror is revealed.

over-made-up, Victorian dolls observing all; and words etched in blood spewed across the walls. There is a small nod to the debate about the supernatural versus enlightenment but it is soon abandoned when the source of the terror is revealed.

The good news is that The Woman in Black does what a film under the Hammer productions banner is expected to. It provides thrills and jumps, some cheesy and some downright scary, while remaining largely free of computer generated imagery. The finale is a little wrought and sentimental, though not enough to derail what has gone before. There are moments of silliness and some straining of credibility in the effort to scare the audience. But give in to it, leave your cynicism at home, and the hairs on the back of your neck will stand proud. You’ll laugh with relief that you survived the next big “BOO!” and grab the hand of your partner. Isn’t that what you want from a horror film?

The Woman in Black is in cinemas nationwide today.