This autumn sees an unprecedented assembly of works by the Pre-Raphaelites, launching at Tate Britain before touring to Washington, Moscow and Tokyo. The exhibition, curated by Alison Smith, Tim Barringer and Jason Rosenfeld, offers a rare chance to view over 180 works, including textiles, stained glass and furniture, whilst exploring the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s revolutionary approach to art and society, including a number of works by associated artists. Many have been borrowed from the Tate’s own extensive collection (usually viewable for free) which will lend an air of familiarity to regular visitors of the gallery.

Ophelia by John Everett Millais

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) was founded in 1848 by the 20-year-old Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and was later joined by William Michael Rossetti, James Collinson, Frederic George Stephens and Thomas Woolner to form a seven-member group. The first modern art movement, the PRB’s mission was to defy the conventions of the day and return to a purer style inspired by the early Renaissance, embracing beauty and naturalism, often in extremely fine detail. The Pre-Raphaelites have dipped in and out of popularity during the past fifty years and this exhibition attempts to re-brand figures once seen as stuffy and moralistic Victorians into dynamic and radical artists and social reformers.

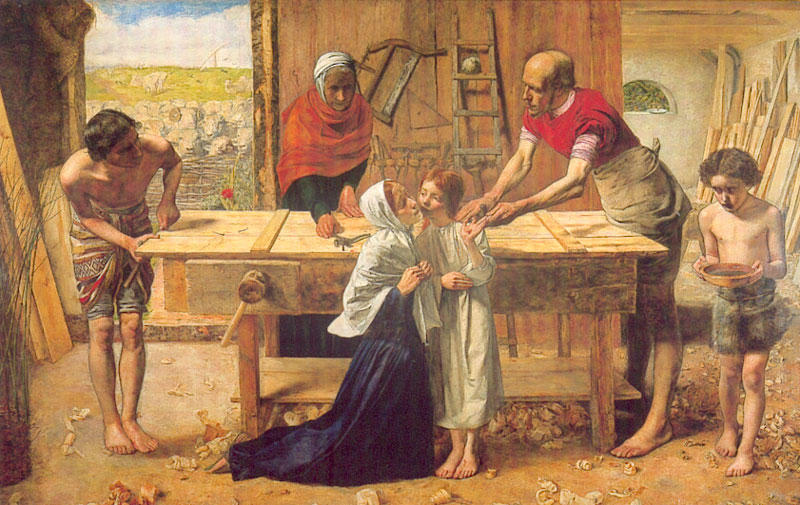

The group received early criticism for their realistic portrayal of religious subjects. When Millais’ Christ in the House of His Parents (1849-50) was exhibited at the Royal Academy, the public were shocked and outraged to see the Holy Family depicted barefoot in Saint Joseph’s carpentry workshop. Charles Dickens publicly attacked Millais’s representation of Mary as “…so hideous in her ugliness that…she would stand out from the rest of the company as a Monster, in the vilest cabaret in France, or the lowest gin-shop in England.” The picture caused so much controversy that Queen Victoria asked for it to be taken to Buckingham Palace in order for her to view it.

Christ in the House by John Everett Millais

The Pre-Raphaelites not only looked to medieval tales, Shakespearean plays and the Bible for their settings, but they were keen to record a modern world in which railways were linking growing cities and science was about to challenge religion. Nor were the Brotherhood afraid to tackle social issues of the day including industrialisation, illegitimacy and emigration. Their art forced a society caught up in the advances of man to reflect upon a natural world that would soon be lost forever, and the effect this would have on society as a whole. The art critic John Ruskin sprung to their defence in a letter to The Times, championing the integrity of the movement, “Pre-Rapaelitism has but one principle, that of absolute, uncompromising truth…down to the most minute detail, from nature.”

Other notable works on display include the staggeringly beautiful Love Among the Ruins by Edward Burne-Jones, The Lady of Shallot by William Holman Hunt, Millais’ Ophelia, and Beata Beatrix (1870) by Rossetti, a posthumous painting of his wife Lizzie – works which revolutionised modern art and had a wide-reaching influence over artists to follow, including William Morris and the founders of the Arts and Crafts movement. But these romantic ideals often gave way to rivalry and betrayal between members. Through the founding of the Brotherhood their lives became inextricably linked, both personally and professionally, but as individual members received more success than others so did the movement begin to unravel; officially disbanding in 1853. The exhibition largely consists of works executed after this period; making tenuous and often confusing links between the original founders and the artists they befriended and influenced.

Love Among the Ruins by Edward Burne-Jones

It’s fascinating to examine Rossetti’s later style, exuding sensuality and celebrating the female form in the guise of classical and tragic heroines, but it was Millais’ later style, as seen in Chill October, that was able to command the most amount of money and led to his work being purchased for use in advertising; something generally frowned upon. From wallpapers to curtains, the term ‘Pre-Raphaelite’ has become as diluted and misunderstood as the Mona Lisa – as witnessed in the gift shop on the way out. Although it was not the exhibition that many lovers of Pre-Raphaelite art might have hoped for, it does provoke thought and inspire a deeper appreciation of the grandfathers of Victorian art.

Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant-Garde at Tate Britain until January 13th 2013. Open daily 10.00 – 18.00, and until 22.00 every Friday. Admission £14. For more information and tickets visit the website.