“The best art in the world today? It’s coming from China, Korea and Iran,” exclaimed Bahman, the engaging New York based Iranian artist whose mammoth canvas we were standing in front of. It was entitled “Nuclear Paradise”, depicted a giant rocket shooting out of a receding earth, and was comprised of seven hundred hand dyed condoms (unused he assured me).

Bahman, Nuclear Paradise, 2013

He may have been biased. Indeed the claim would have come as a surprise to George W Bush who famously labelled both Iran and North Korea as lying within the “Axis of Evil”. But to collectors, artists and the fine art cognoscenti, Bahman’s bald assertion is on the money. It is certainly no surprise to the Opera Gallery (represented from New York, Paris and Geneva, to Dubai, Hong Kong and Singapore) who are this month hosting in their New Bond Street premises an exhibition of contemporary Iranian art entitled “Peace from the bottom of my art”.

It has been said that all art is political. In a country like Iran where the business of state is forced upon people on an almost daily basis, it is perhaps impossible to avoid the political in creative expressions. It is all credit to the Opera Gallery then for taking the bull by the horns and giving their chosen artists a theme to work with that is not normally associated with the country by the Western media – peace. Of course there is no avoiding the flipside of this – war – and many of the artists on show chose to explore the dividing line between these two states. As Bahman said to me of his some what unusual materials,

“I am interested in dichotomy, which is why I chose to work with media not normally associated with war, and to do it in a childlike style.”

Koorosh Angali, Crucifix, Homage to Salvador Dali, 1983

There are fifty five artists on show, one of who is Iraqui and another who is an ethnic minority Kurd. There is a high proportion of women artists represented which might confuse the casual observer who would assume the Iranian state would frown on such things. In fact, despite the compulsory use of headscarves in public, Iranian women have always enjoyed a degree of emancipation unknown amongst many of their Islamic neighbours. Female students at university now outnumber men by a considerable margin.

As a film-maker I have long been aware of Iran’s reputation in world cinema. (Excitingly, one of the visionary masters of the art, Abbas Kiarostami, also a photographer of some renown, has a photograph in the exhibition – a vast white snowscape crossed with telephone lines with a single tree at the bottom. Bare and simple, it exudes a stark, lonely power.) I had often wondered how these film-makers were able to produce works of such artistic integrity under such repressive conditions. They do, amazingly enough, just as writers and musicians produced some brilliant work under Stalin and under countless other regimes down through the centuries. Foolishly then I had assumed that most of the artists on show were exiles. Maybe it had something to do with the immediacy of the visual in art, that it is in some ways more difficult to hide subtext in this form and that contemporary art has a reputation for shock value (just think of the Y.B.A’s). I was wrong though. Many were based abroad, in Germany, France, the US and here in Britain, but a greater number still lived and worked in Iran. (Ironically perhaps, due to the recent closure of the British embassy, none of the artists based over there were able to secure visas to attend their own exhibition. The five who were there and who I spoke to all lived overseas. Once again, art and politics made for unwilling bed partners.)

So what of the art? It was a question I asked of many of those I spoke to, and especially the artists. “Off the record?” offered Afshin Naghouni, a personable and passionate painter and mixed media artist confined to a wheelchair whose large canvas entitled “Universal Soldier” depicted a helmeted fighter with a pixilated face. “There are a few works that are a bit weak, but on the whole, really impressive.”

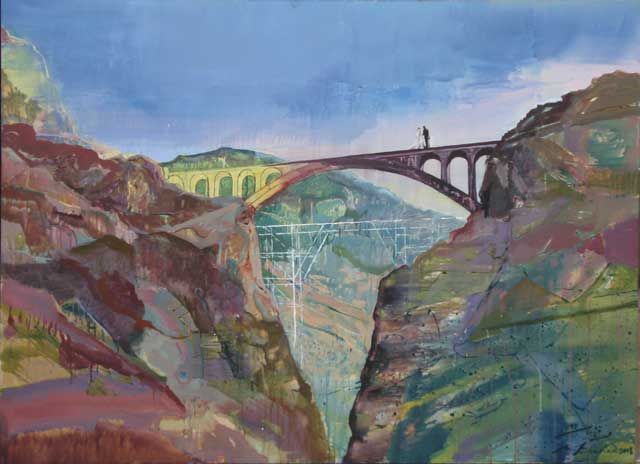

Manouchehr Niazi, Untitled, 2013

And so much of it was. But it was more complicated than this. At least for me. Because I am Anglo Iranian, born there, with an English father and an Iranian mother and an outlook which has been forged from the Western canon. But still, having never really lived there, having never returned since my infancy, there is something in me that flutters at the thought of this ancient and beautiful land. Perhaps my heart is in Iran (literally my mother land) whilst my head remains defiantly British – rational, reserved and a trifle cynical.

Yes, art is universal, at least good art is, but it is also formed from cultural and historical traditions, from peace and strife. Iran is an old country with two and a half thousand years of civilization – half of that pre-Islamic. The arts and artisanal crafts (which in the hands of the master are undoubtedly art) have always been strong there, witness the weaving in their exquisite carpets, their pottery and ceramics, their metalwork, tilework, architecture, garden design, calligraphy, poetry, music and painting (with their unique ‘miniature’ style being widely copied elsewhere in the east). The colours and patterns, developed from age old customs and the instinctive feelings of the people, are often mirrored in different forms. Those familiar with the rich hues of their rugs, the geometric designs, the twisting tendrils of florae and the proliferation of beasts, would find similar designs in their gardens, pottery and in the tilework of their mosques and in the tombs of their poets.

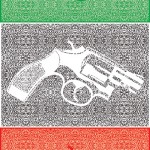

Iman Safaei, The Nature of Peace, 2013

Much of this style and sensibility can be seen infused in the works in “Peace from the bottom of my art”. In the flourishing line work and colours of Koorosh Shishegaran’s two works on display – the globe on blue background in “For Peace on Earth” and the two very different birds in “Two Birds” – there is something distinctively Persian and almost calligraphic in their depiction. In Roxana Manouchehri’s gothic panelled triptych, she employs the classic Persian miniature technique with Celtic and Byzantine elements to confound expectation. Indeed this is something like a reprise in the exhibition, the collision of Persian and Western art and the entrance of Modernism. In Iman Safaei’s “The Nature of Peace, dedicated to Andy Warhol”, the clue is in the subtitle. Comprised also as a triptych, this time vertically mounted, each panel is coloured with the hues of the Iranian flag – green, white and red. The highly ornate back patterns on each panel are recognisably Iranian, but embossed in the centre is the image of a revolver. “Peace is a Dream” declares the young artist. Here Warhols’s pop art is given a sinister subtext. If politically and religiously the country has turned its back on the West since the Islamic Revolution, then the exchange of ideas has continued, no doubt abetted by the internet. Amongst artists and creatives at least, there has been no stasis of culture.

Still, in my question, “What do you think of the art?” there was an effort in myself to reach a deeper understanding of what I was looking at. Despite my Iranian heritage and feelings of ‘otherness’, I couldn’t help but looking through Western eyes. I haven’t personally experienced the rift of violent revolution, of a war that claimed the lives of millions of my neighbours. I haven’t experienced that yawning sense of loss.

“Your sense of the piece changes according to where you stand,” explanined Azadeh Ghotbi, a striking lady with a string of enormous turquoise stones around her neck. We were standing in front of her wall mounted sculpture entitled “Give PEACE a chance to soar” which consisted of a black rectangular metal cage in which the word “peace” was held. Sitting on top of the cage was a blue ceramic bird. “If you step to the left or right, or crouch down, you will see the blue on the sides of the letters. The colour is turquoise which is a very special colour in our culture.” The bird was coloured in the same pigment. “I was going to put it (the bird) inside the cage but I just couldn’t so I put it on top and left the door in the side open.”

Parviz Tanavoli, Love the Birds, 2013

The image of the bird is one that reappears in different forms in a variety of the works on display. And this is not just the cliché of the dove of peace (the birds rarely resemble doves anyway). The bird is a potent symbol in Persian poetry and art. In Maryam Salour’s “Peace”, the long, bending figure cast in brown ceramic has a bird on its shoulder – once again, coloured that striking turquoise. In a photograph by Hamid Sardar-Afkhami entitled “Rustam holding young falcon”, the young Kazakh boy with the plain and mountains behind him and the bird of prey gripping his gloved hand, conjures the legendary hero king, who is to Iranians what Arthur is to the English.

The frontispiece to the programme is of a little yellow bird sitting in an outstretched hand. It is a beguilingly childlike print by perhaps the most famous artist in the exhibition, the renowned Parviz Tanavoli. When I showed the image to my mother she responded, “It gives me a funny feeling in my heart.”

“Thirty four – you’ll hear that number a lot tonight,” remarked Azadeh Ghotbi.” It is the number of years that have elapsed since the Islamic Revolution when many of those present were forced into exile. “I perennially question what it means to be Iranian and Middle Eastern when one has lived away this long from that part of the world. Yet the feeling of belonging and longing is beyond my control. It’s purely emotional and deeply instinctive.”

Peace and return may be some way off for the people of Iran, but what shone through in the exhibition was the resilience of hope.

The exhibition runs at Opera Gallery London, 134 New Bond Street, until 9th May 2013. For more information, visit the website.