In the second part of Harry Chapman’s short story, Louis’s situation goes from bad to worse as he finds himself at the bottom of a well, injured, and with the snow falling incessantly…

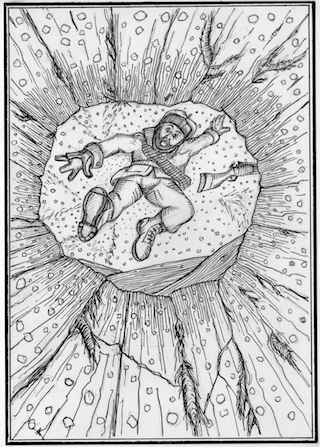

After tearing his eyes from the spiralling particles of snow, he allowed them to roam; this seemed easy and acceptable. He had tumbled into a sort of natural well. He must have knocked aside a fallen log when he fell which had acted as a lid because the hole was only part filled with snow. Enough though to cushion his landing to some degree. Tree roots erupted from the frozen walls of the crevasse, stretching out to him like hairy hands.

He began to feel the cold. It was the first thing that reminded him that he wasn’t just a floating thought, a wandering consciousness in the fabric of the environment. He freed a hand and fingered his bicep where he had felt the first impact of the crash. It seemed remote, detached, as though he were feeling the length of a familiar possession rather than part of his own body. There was no pain so he gave up, unsure of what else he was seeking.

He began to feel the cold. It was the first thing that reminded him that he wasn’t just a floating thought, a wandering consciousness in the fabric of the environment. He freed a hand and fingered his bicep where he had felt the first impact of the crash. It seemed remote, detached, as though he were feeling the length of a familiar possession rather than part of his own body. There was no pain so he gave up, unsure of what else he was seeking.

With effort he turned over and extracted his twisted leg. He slowly got to his feet. Three things happened simultaneously. He screamed, dropped to the ground, and a searing bolt surged up his spine and flashed over his brain. It was so unexpected that for a few moments he remained in the position he first found himself; face forwards, hands splayed, as though in prayer. He realised that it was pain and that it must have sprung from his own body. But it was like nothing he had ever felt before. He was entering into a whole new territory, a new world of experience. And he was scared.

Slowly he raised his torso and using his hands to brace himself against the sides of the hole, once again attempted to lift himself. The same thing happened once more and with an involuntary cry he found himself curled up on the ground. But there was no surprise in it this time and what was more, he had located the source of the pain. It was his right ankle. Grimly he concluded that it was broken.

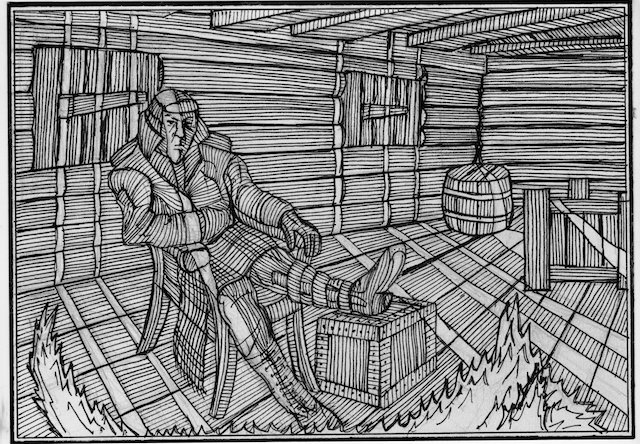

He delicately rolled into a seated position, careful not to apply any downward pressure to the foot. Whether it was because the circumstances he found himself in were so dire, and it was his mind’s way of coping, or because he had gone into a kind of shock, the enormity of the situation eluded him. He felt a little sad, a little tired and a little put out that he had been so inconvenienced.

He looked up at the sides of the shaft. They were glossy and forbidding in places, but in others there were protruding hand-holds of rock and root. The first thing he needed to do was to splint his damaged foot, but amongst the pine cones and sticks at the bottom there was nothing sturdy enough. He would have to make the climb with his right foot dangling free, like an injured wing.

Hauling himself up, he rotated on the heel of his good foot as though it were a draughtsman’s compass, and scanned the walls for the best route. He reached up for a nose of rock. He was determined to start without breath or ceremony, to do it simply by getting on with it.

He eased up his shoulders, lifted his left foot and dug it in. Immediately his right leg swung in and struck the wall. He screamed. The pain was as bad as the first time; experience didn’t make it less. He squeezed shut his eyes and whimpered, surprise mixing with indignation as though he were a hurt child. He waited for the pain to contract to a dull glow and then shot his hands out, one high, always reaching, taking him up, the other at body level, consolidating ground, steadying. His left foot acted as a sort of spike, taking some of the weight, but in moving, the entire bulk of his body and limbs was borne by his arms and shoulders. He hugged the wall face as closely as possible to spread the weight, but it was exhausting, painstaking work. Sweat popped at the back of his neck and ran down under his collar. On the reverse his cheeks slid across the frozen face of the shaft. Alternating hot and cold – it was a strange harlequin effect but one whose very changeability kept him braced, pushing forwards. His heart beat steady and loud, seemingly at his throat. Slipping, falling was impossible to countenance. The pain alone would finish him.

In this way, his world reduced to grunts, hand-holds and sideways shifts, he slowly climbed the well. It was difficult to control his hanging right leg and periodically it would swing in and make contact with the wall. When he felt this about to happen he would shut tight his eyes and clamp hard to whatever he was holding. The pain came as a white light. It burned ferociously, sucking out his breath, scooping out every thought apart from itself. He found chewing the lapel of his coat helped control his reaction. He bunched more and more of it into his mouth the further he got. When he finally rolled out onto the snowy ground at the top, he discovered he had bitten right through it.

He lay on his back for a few moments, eyes fluttering in the falling snow, his pounding breath gradually returning to normal. The worst was over but he still had to make his way back to the cabin. He crawled over the drifts and debris and felt his way up the trunk of a tree, holding his injured leg straight out like a rudder. He snapped off two dead and relatively straight branches. One was short which he tied tight to his broken leg with his scarf. The other was long, and clamped inside his armpit, made a rudimentary crutch. The gun was gone; at least he couldn’t see it anywhere, and he wasn’t going to waste energy floundering around in the half light.

Louis headed for what now passed as home. The cabin was only about a hundred yards away, but the snow was deep. Even with two sound limbs the going was hard; with one gammy one it was tortuous. Naturally he simply wanted to slide his bad leg forwards, as close to the ground as possible, but the depth of snow didn’t allow it. Instead he had to rotate it out to the side in a wide arc, like Charlie Chaplin twirling his cane. The effect would have been comic if it wasn’t so sapping, and the circumstances weren’t so grim. Once more it took all his powers of concentration. His muscles were perpetually braced just to keep him upright and to prevent his leg falling too fast or clanging against any obstructions. He slipped twice but didn’t fall. By the time he got back to the porch the back of his shirt was ringing wet. He was moaning a kind of tuneless dirge and he realised he was close to tears.

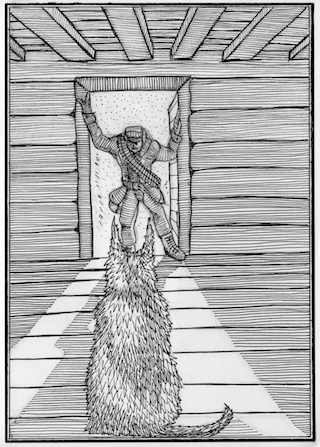

He pulled the door open and scraped in. The room felt warm after his exertions and also strangely silent. It was as if all sound had been drawn out. It felt as though a sentence had ended abruptly in the middle and everything had been left hanging, waiting.

He pulled the door open and scraped in. The room felt warm after his exertions and also strangely silent. It was as if all sound had been drawn out. It felt as though a sentence had ended abruptly in the middle and everything had been left hanging, waiting.

Louis suddenly felt very weak. He had been working on borrowed energy and now felt the dizzying lack. He lurched across and eased himself into a chair. The dog followed him like a shadow and worked its muzzle into his hands. After all he’d been through and the situation he found himself in the effect was immediate and electric. To receive an affectionate touch, to feel the warmth of another’s body, especially one that he loved and that loved him, was overwhelming. He drew the animal in, wrapped his arms tight about it, and buried his face in the thick fur of its shoulder. His body began to heave with dry sobs, huge juddering paroxysms that he couldn’t account for and couldn’t control. Then the thought stole back on him, twisted and runtish, with a pale, glowing face. It was so repugnant now it made him feel physically sick. He had actually considered killing the dog for food! Was he a different man then? What switch had he inadvertently flicked on? He tried to squash the thought, grind it into the dust of oblivion.

The dog was moving. He could feel it nuzzling him. He could hear it licking. They were concentrated, fixed on one area. His bicep. The one that had felt the clash of horns.

He pulled away. He could feel the strength of the animal, its weight and resistance. He shoved it back. It was breathing quickly. Its foetid breath clouded the air. There was blood on its tongue.

“Non! Loupo!”

Its jaws snapped shut. It stepped back.

He reached round and fingered his bicep. He could feel the ripped edges of his jacket arm. Beyond this his fingers encountered something wet and warm. He drew his two fingers to the light. They were sticky with a heavy tar-like substance which looked black in the cabin. Blood. His blood. His arm felt slightly numb. He tried to flex it. It was beginning to seize.

He looked at the dog. It was sitting now, staring back at him. Its mouth was open again and when it caught his gaze, it shut it again abruptly.

Unconsciously Louis lifted his hand and held his injured bicep. Dogs licked their masters for different reasons – of course for affection, to derive the salt from sweat. Naturally they were attracted to wounds also. He had heard tell – and he didn’t know if this was an old wives’ tale – that dogs have a curative substance in their saliva. Perhaps Loup sensed his distress and was trying to administer to him?

He felt an incredible thirst which seemed to consume him as soon as he thought of it. He raised himself with difficulty and lurched to the fire. The pan was half full. He tipped some out for the dog, the rest he poured straight down his throat in long heavy glugs, his chin forming a line with his neck, his adam’s apple bobbing in unison with the workings of his jaw.

He sat down heavily in the chair. He felt light-headed, drunk. The dog glanced briefly at its water bowl and then back at him. It snapped its jaws together. They sprang back open, as though on a hinge. The lower one twitched, up and down, in time with its breathing. Saliva gathered at its gums and spooled over its black lips, hanging in long uneven strands. It shuffled forwards on its haunches.