Celebrated portrait photographer and film-maker, Paul Joyce, recalls a youthful narrow escape with the legendary sculptor Henry Moore in October 1975…

By the time I met Henry Moore at his house and studio at Hoglands, Much Hadham in Hertfordshire, he was our most famous British sculptor and earning enough to have to pay one million pounds a year in tax to the government. This he circumvented by setting up the Henry Moore Foundation, a charity devoted to the dissemination of visual culture and the promotion of the artist’s own works.

One’s first impression was of a short, compact man, and one who had been fighting, and mainly losing, a battle against incipient baldness most of his adult life. He was a somewhat gruff, plain-spoken northerner who clearly did not suffer fools gladly and had practically nothing to offer by way of polite conversation. This suited me just fine as I had come to take pictures, not sit around with cups of Bovril (by all accounts a favourite mid-morning tonic of his).

Moore was much intrigued by my camera equipment which consisted mainly of a specially made mahogany and brass 5 x 4 plate camera by the Gandolfi Brothers. I would make sure that the setting up of this equipment, on a classic wooden tripod of the period, would be a lengthy procedure which usually fascinated my subjects and allowed for a measure of pre-photography chat. In this Moore was certainly no exception and I subsequently learned that he had a great interest in photography and practised it at a high-end amateur level.

Hoglands, his house and studio complex, was a rambling and barely heated series of buildings like some kind of attenuated farmyard. The house itself, of indeterminate period, was draughty and rather unwelcoming, so I asked to see his studios and workshops and this request brought him somewhat to life.

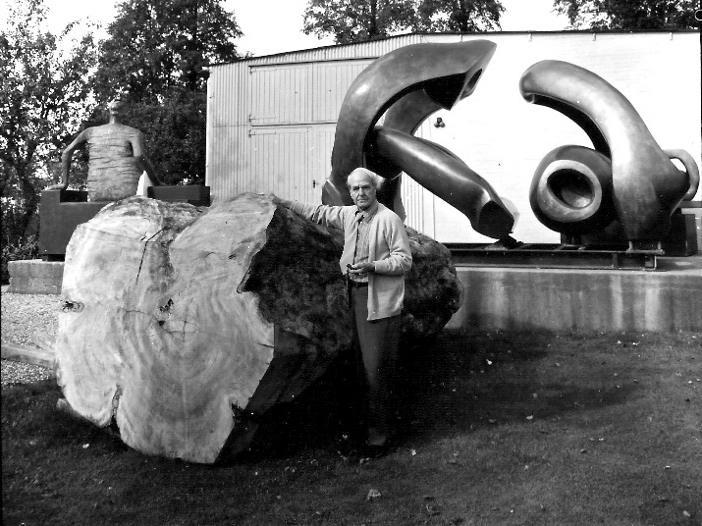

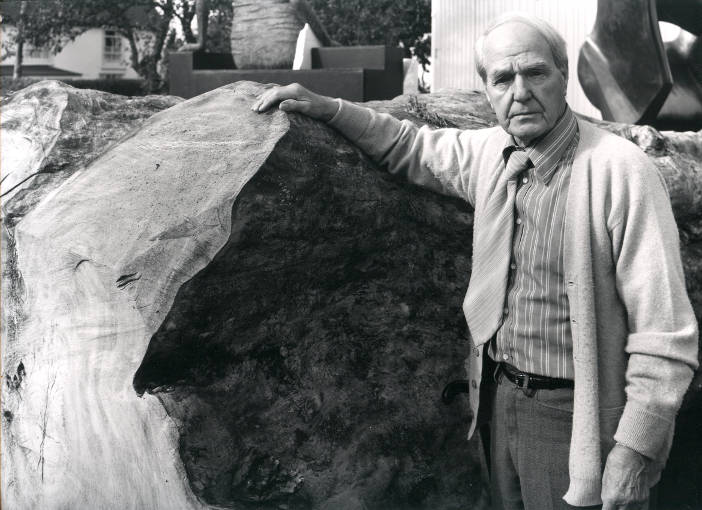

As we made our way outside and towards the outbuildings, the roar of a lorry with low-loading capabilities announced its presence in the driveway and Moore waved it past, directing it towards a garage complex at the back of the house. The lorry contained two giant tree trunks with MOORE scrawled roughly on them in black paint or creosote. I said, “Surely you must have a wealth of wood at your disposal here in the countryside?” and he turned to me with great seriousness and replied, “Wood is only really useful to a sculptor if it is cut down especially and freshly. It needs to be ‘green’ to be able to be properly worked.” Soon we were in his maquette studio where there seemed to be dozens (if not hundreds) of carved or plaster miniature ‘testers’ which he may or may not work up into larger pieces in the future. Of all he showed me that day, this was clearly the creative powerhouse of his whole operation.

At one point he reached out to a medium-sized wood piece of a reclining figure, waiting to go to an upcoming retrospective in Italy, and stroked it lovingly. I said, “Some of your work has a very sensuous aspect to it, one wants to reach out and touch it.” He replied, “Yes,” stroking the sculpture again, “but we can’t have the whole world and his wife doing the same!”

Then he wanted to know how my portrait of him would be achieved and I thought of the great tree trunk, just delivered, and suggested a portrait with him in front of it. A change of location like this gives me more time to think, as I have to deconstruct the camera and tripod, and then relocate and set-up all over again. So while I was doing just this, he excused himself to relay instructions to the couple of assistants who seemed to be lurking just out of sight (but not consciousness). Whilst he was so engaged, I managed to take a couple of pictures on my other more manageable camera (a Mamiya with a 6 x 9 rollfilm back) of the maquette studio – just for the record!

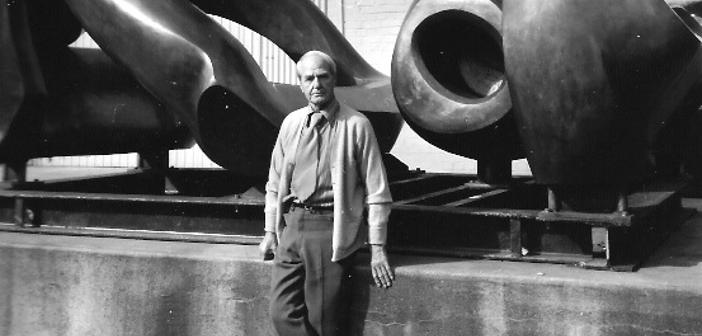

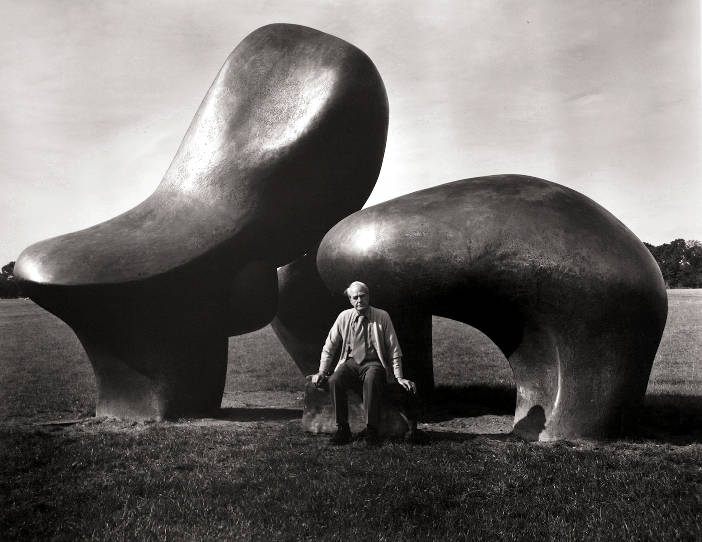

After I had taken his portrait by the timber trunk (4 or 6 separate set-ups as I now recall) I asked him if he had any larger scale pieces in storage or accessible, so I could photograph him in relation to the work itself. He smiled and beckoned me to follow him through the “farmyard” and out into an adjoining field. Here was a large-scale work sure enough. I looked around to see if there was something I could sit him on in front of the work, but nothing was close at hand. Then, in a far corner of the field, I spotted an old tree stump – but it was at least a hundred yards away. I pointed, excused myself for a moment, hurried over and put my shoulder to it to try and roll it over towards my curious subject. Finally I got it on the move and pushed and shoved it for what seemed like a mile until it was more-or-less in front of the sculpture and its creator.

Moore watched this sweaty procedure with a mixture of amusement and admiration, and said to me “You are clearly quite strong; how would you like to come and work with me as my assistant?” I managed to somehow duck this offer, which even in my palpitating state I recognised as clearly a poisoned chalice, and set about composing the portrait which in the end would define our session together. I wanted to know, for example, when he decided to make a small individual animal’s vertebra into a monumentally scaled piece, how that decision and choice came to be made? This was clearly a question too far either undeserving of an answer, or impossible to frame a reply to. So silence reigned, at least temporarily.

We were now running out of time, and I suspected he was losing patience. But, as a huge admirer of the work of Paul Nash, and knowing they had been involved in the short-lived British Surrealist movement, I had a few more questions about matters arising. I mentioned that Nash, who practised photography really very seriously, wrote sometime in the 30s that he was concerned that his reputation as a photographer would – unless he was very careful – eclipse that of his painting. Moore smiled and admitted to being a serious amateur photographer himself, and it came to me then that a book examining the photographic work of Nash, Moore and John Piper (who I also knew and had photographed) might make a great project. I asked what equipment he used and he replied, “Just a standard Leica.” Well there is no such thing as a standard Leica, they are all special and help define top-end professional equipment. By now my welcome was well used up, but he hurried away and then came back with some prints to show me: excellent images of sheep, tree stumps, stone gateposts and close-ups of hedgerow vegetations. I mused that these photos might have been taken by Nash, Piper or even Graham Sutherland, for the subject matter would have appealed to all of them equally.

So I packed up and left, agreeing to keep in touch. He waved me away courteously at the front door, saying “Don’t forget, if the film-making doesn’t pan out, you can always come and work here!”, and as I stumbled down the drive to my Morris Minor, waiting patiently on the road outside, one of his assistants appeared. I called to him and asked what it was like working for Moore. The reply came as the iron gate banged shut behind me: “He’s a mean old bugger – pays very badly.”

Photography (c) Paul Joyce