Gordon Parks’s photographs are large and colourful, capturing the pastel-hued dresses, the bright red cars and the blood red clay of the American South.

In Shady Grove, Alabama, there’s a familiar scene of a father buying his children ice cream. Taken in 1956, the kiosk is full of adverts in curling ’50s typography marketing tasty hot dogs, root beer floats, banana splits and butterscotch sundaes. In amongst the busy adverts, it takes a moment to notice another sign hanging above the family, who stand at a side window. It says ‘Colored’. A window labelled ‘White’ takes centre stage. Shot from a distance in soft, muted tones, the scene offers a stark glimpse of this family’s everyday life.

Untitled, Shady Grove, Alabama, 1956. Courtesy of The Gordon Parks Foundation, New York and

Alison Jacques Gallery, London. © The Gordon Parks Foundation.

Parks was born in segregated Kansas in 1912, the youngest of 15 children. He left home aged 14 following his mother’s death and ended up on the streets shortly after. The dangerous experience of being black in America was something he wanted to give a voice to, despite the threat to his safety; a threat with which he was already familiar. As an 11-year-old child, three white boys had thrown him into the Marmaton River, knowing he couldn’t swim.

“I suffered first as a child from discrimination, poverty,” he explained. “So I think it was a natural follow from that that I should try to use my camera to speak for people who are unable to speak for themselves.”

As a multi-faceted artist, some know Parks best as the director of the 1971 film Shaft and an architect of the Blaxploitation film genre. Others may know the music he composed or the poetry he wrote. But aged 25, his career started as a portrait and then documentary photographer, before doing fashion shoots for Vogue and moving to Life magazine – the pinnacle of contemporary journalism – where he was their first black photojournalist, working there for two decades.

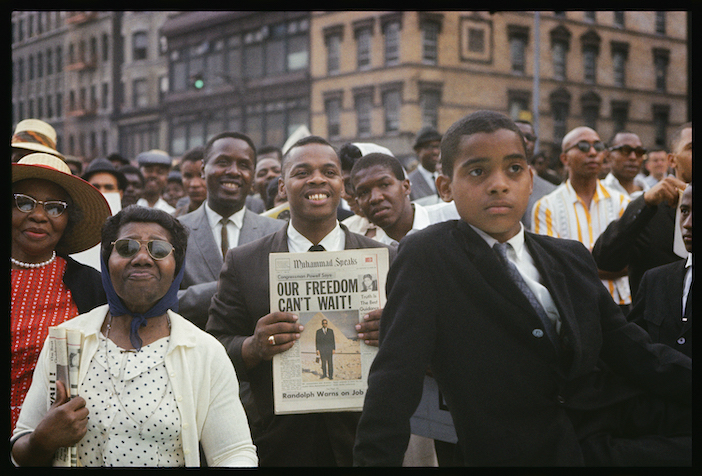

Untitled, Harlem, New York, 1963. Courtesy of The Gordon Parks Foundation, New York and Alison Jacques Gallery, London. © The Gordon Parks Foundation

His assignments saw him document Harlem gangs, state executions and vicious crime scenes, amongst others, but this exhibition focusses on two stories he produced for Life against a backdrop of the rising civil rights movement.

Segregation in the South (1956) follows three black families living in Alabama, while Black Muslims (1963) documents the growing Nation of Islam movement. Parks’s photographs of Muhammad Ali, taken between 1966 and 1970, will be on show for part two of the exhibition in September.

In deciding how to convey something as complex as structural racism, Parks chose to focus on the individual lives of black Americans. He said the problem with photographing bigots was that they had a way of looking just like anyone else. Instead, he showed the impact of bigotry, and humanised his subjects’ experience through his lens. At a time when protests and violence were rising, Parks’s quiet photos depict everyday life in gentle tones. But the unspoken threat of violence gives them a heightened emotional quality.

Untitled, Shady Grove, Alabama, 1956. Courtesy of The Gordon Parks Foundation, New York and

Alison Jacques Gallery, London. © The Gordon Parks Foundation

For Segregation, he spent time getting to know the families he documented and their ease in his presence is clear. But their expressions are often sombre or wary. There’s the mother holding her child dressed in Sunday best, her look of concern piercing through the scene of blue and turquoise dresses, above the child’s lacy bonnet. Elsewhere a young girl gazes straight into the camera with mature, wistful eyes that seem misplaced in her child’s face. And there’s the boy crouching in the ochre mud, frowning into the distance whilst the camera captures his friend’s bare, bandaged feet.

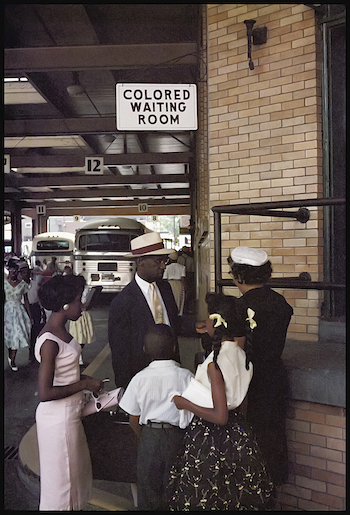

Beautifully shot and composed with the eye of a portrait photographer, Parks’s images have a collaborative feel. The quiet elegance of his photographs is at odds with the indignities he captures, including the carefully cropped photo of an immaculately dressed family waiting at a bus station. The ‘Coloured waiting room’ sign above them brings tension to the intimate family scene.

Untitled, Nashville, Tennessee, 1956. Courtesy of The Gordon Parks Foundation, New York and Alison Jacques Gallery, London. © The Gordon Parks Foundation

During this assignment, whilst hiding out in a shanty one night for safety, Parks wrote in his diary:

“Just a few miles down the road Klansmen are burning and shooting blacks and bombing their churches. Southland is afire and lying here in the dark, hunted, I feel death crawling the dusty roads. The silence is spattered with fear.”

In his photographs, that silence speaks loudly. Scenes in Segregation set the context for Black Muslims. Peaceful and dignified, his black and white images provide a different lens to the one offered by the mainstream media. There’s Malcolm X, arm raised in a classic presidential pose, and Ethel Sharrieff, wearing a habit, surrounded by solemn nuns.

Elsewhere, a dark scene of protest looks strangely serene, with stark placards speaking for the blurred crowd: ‘We are living in a police state’ reads one. ‘Liberty or death’, another. At the centre of the image, a white policeman, metal uniform glinting, looks away.

Parks’s striking aesthetic and technique of slowing down scenes to convey their emotional complexity creates an excellent exhibition, reflecting critical moments in American history. What is especially poignant, however, is its relevance today.

Gordon Parks: Part One is showing at the Alison Jacques Gallery until 8 August 2020. Part Two of the exhibition runs from 1 September to 1 October 2020. For more information and tickets, visit www.alisonjacquesgallery.com.

Header image: Gordon Parks. Untitled, Alabama, 1956. All images courtesy of The Gordon Parks Foundation, New York and Alison Jacques Gallery, London.