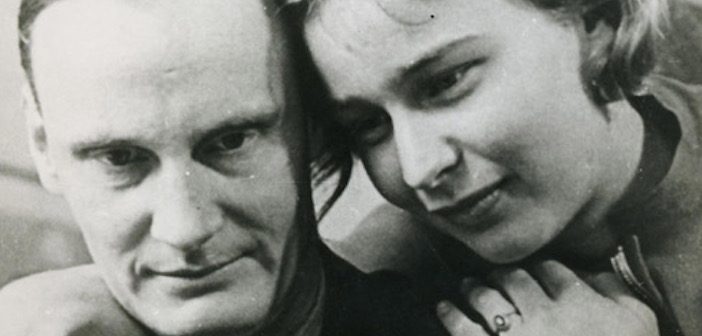

At the heart of The Infiltrators is a love story. A handsome young couple, Harro Schultze-Boysen and Libertas Haas-Heye, dare to actively oppose the Nazi regime while working inside its institutions. It’s a tale of an ultimately hopeless cause and of courage in the face of death if discovered. It’s also a thrilling and fast-paced read, which is not unexpected as it comes from Norman Ohler, prize-winning novelist and screenwriter. However, The Infiltrators is not a novel but a true story, meticulously researched by Ohler.

Harro came from a prosperous family with impeccable connections, the most important being his great uncle Admiral Tirpitz, founder of the modern German navy. Harro was a handsome young man, tall, charismatic and articulate. He was already a politically active student, liberal and open-minded rather than ideological, when the Nazis seized power in 1933. It was the sustained beating he and two friends received from the SS, resulting in the death of one of them, that turned him into a dedicated opponent of Nazism.

Harro came from a prosperous family with impeccable connections, the most important being his great uncle Admiral Tirpitz, founder of the modern German navy. Harro was a handsome young man, tall, charismatic and articulate. He was already a politically active student, liberal and open-minded rather than ideological, when the Nazis seized power in 1933. It was the sustained beating he and two friends received from the SS, resulting in the death of one of them, that turned him into a dedicated opponent of Nazism.

Libertas was a beautiful, lively, aristocratic girl from a family with a castle and an intriguingly scandalous past. She aspired to be a writer and worked initially for the publicity department of MGM films in Berlin and then as a film reviewer for the National-Zeitung, one of the more moderate Nazi newspapers. One of her parents’ neighbours was Goering, the head of the Luftwaffe, the German air force. It was her persuasive charm that swayed him into granting Harro an officer’s commission in the Luftwaffe. Despite her connections, she was a free spirit and got to know Harro because they both loved sailing. As a couple, they became known for their parties, their skill as dancers and their interest in the arts.

Harro’s job in the main Luftwaffe headquarters in Berlin gave them their first opportunity – collecting intelligence about German support for Franco during the Spanish Civil War and handing it on anonymously to the Soviet Union. Then they began to print and distribute anti-Nazi leaflets often just left in phone booths. Later, they would tell the Soviets about German preparations for the attack on Russia. Their most openly public act was to paste anti-Nazi messages over the posters advertising a propaganda exhibition about the Soviet Union organised by Goebbels, head of Nazi propaganda – followed by the planting of incendiary bombs in the exhibition.

In a tragic irony it was a surprising lack of clandestine radio security by the Soviets that helped lead to the unmasking of the group in 1942. Seventy-seven were put on trial with over 50, including Harro and Libertas, being sentenced to death and executed in the Plotzensee Prison in Berlin. The prison is still in use and the execution building is now a little known memorial to its 3,000 victims of Nazism.

In a tragic irony it was a surprising lack of clandestine radio security by the Soviets that helped lead to the unmasking of the group in 1942. Seventy-seven were put on trial with over 50, including Harro and Libertas, being sentenced to death and executed in the Plotzensee Prison in Berlin. The prison is still in use and the execution building is now a little known memorial to its 3,000 victims of Nazism.

The publisher’s sub-title ‘The Lovers Who Led Germany’s Resistance Against the Nazis‘ is misleading. There was never the co-ordinated resistance to the Nazis this implies. By the end of 1934 they had already seized control of the machinery of the German state, banned all other political parties and destroyed any possibility of widespread organised resistance. Opposition thereafter was essentially limited to social networks that grew from the informal gatherings of like-minded friends. What contact there was between these networks was often limited and frequently just accidental. The people connected with Harro and Libertas formed just such a group with Harro acting not as leader (there was no leader as such) but as the principal link connecting the different strands of a loose group that never involved much more than about 150 people.

Those courageous enough to oppose the Nazis were always small in number. Indeed, historians of the opposition to Nazism have often referred to it as a ‘resistance without people’. Faced with the ruthless use of violence that lay at the heart of the way the Nazi regime conducted its business, few were prepared to risk their lives voluntarily when there seemed so little chance of success and when the overwhelming majority of Germans appeared to support the regime or, at least, outwardly conform to its demands.

The violence directed at any Germans regarded as enemies of the regime was implacable. Executions rose from 180 or so during the thirteen years of the Weimar Republic to well over 16,000 under the twelve years of the Nazi dictatorship. This does not include the 20,000 condemned to death by military courts or the thousands who died of mistreatment or were simply murdered while in prison or in the six concentration camps within Germany itself. These camps already held 600,000 inmates by 1939. To put this in context, England only saw 158 executions during the same period.

Ian Kershaw, the eminent British historian, did not overstate the daunting challenge faced by the German opponents of Nazism when he wrote ‘so lethally dangerous was the Nazi regime to its opponents that, as with a cobra, hitting at the tail was likely to result only in being destroyed by the head.’ Once the Nazis had seized power the only institution that remained with the ability to cut off the head of the cobra was the Wehrmacht. With the exception of the failed 1944 July bomb plot, the activities of those opposing the regime were little more than irritations – but irritations for which thousands paid the same terrible price as that exacted from Harro, Libertas and their friends.

Manfred Roeder, the senior judge who led the prosecution of the group declared bombastically to Harro’s mother after his execution ‘the name of your son is to be expunged from human memory for all time’. Harro, though, has had the last word in his final poem hidden in a wall of the Gestapo headquarters in Berlin. Against all the odds, it survived the war.

Hangman’s rope and guillotine

Won’t have the final say.

The world will be our judges,

Not the judges of today.

The humanity with which this eloquent and superbly written book brings Harro, Libertas and their friends to life makes a mockery of Roeder’s claim. In so doing it also captures the schizophrenic atmosphere of the lives they lived under a totalitarian regime. The book is no hagiography but an honest and deeply researched portrayal of two brave young Germans trying to live life to the full while risking their lives in what were destined to be vain attempts to resist a merciless tyranny.

The Infiltrators by Norman Ohler is published by Atlantic Books. RRP £20 (hardback). For more information, visit www.atlantic-books.co.uk. Available at Waterstones.com and all good stockists.