Picasso is quoted as saying that art washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life. With so many exhibitions cancelled or postponed this year, that dust had been accumulating, and so it felt particularly exhilarating to walk through one of Europe’s most notable collections of Impressionist art, on show at the Royal Academy.

Gauguin and the Impressionists presents 60 paintings on loan from the Ordrupgaard collection in Denmark. Amassed by insurance magnate Wilhelm Hansen and his wife Henny in the early 20th Century, they envisioned a collection that spanned ‘from Corot to Cézanne’. The result is an enthralling journey through Impressionism – from its forefathers to its champions and reactionaries.

Camille Pissarro, Plum Trees in Blossom, Éragny (1894) © Ordrupgaard, Copenhagen.

With paintings by Delacroix and Corot in the 1830s through to Matisse’s Flowers and Fruit in 1909, the exhibition’s breadth helps contextualise the different artists who moulded the movement, from Monet to Manet, Renoir, Sisley, Degas and Pissarro. It culminates in a finale of post-Impressionist art by Matisse, Cézanne and the exhibition’s eponymist, Gauguin – ending with eight dazzling paintings by the controversial artist.

In an interesting take, the curators have steered away from a purely chronological approach and instead combed the collection into three strands – En Plein Air, Collecting French Masters and Impressionist Women. Opening with En Plein Air, the first room explores the Impressionist technique of painting outdoors. A beautiful winterscape by Pissarro sets the tone: Snowy Landscape, Éragny, Evening, 1894 is delicately aglow, its lambent sky melting gently from gold to orange and its snowy foreground a masterful blend of white, lilac, peach and blue.

Berthe Morisot, Young Girl on the Grass (1885)

© Ordrupgaard, Copenhagen

Further along, three paintings by Sisley capture a distinct shift in his style. Line of Chestnut Trees at La Celle-Saint-Cloud, 1865 and The Flood, Banks of the Seine, Bougival, 1873 show the clearer aesthetic and more traditional hues of his earlier work, whilst the suburban Seine scene of September Morning near Saint-Mammès and the Veneux-Nadon Hills, 1884 is full of the energised brushstrokes and bolder colour combinations he later explored. It’s also interesting to witness the shift in Monet’s work, from his plainer Seascape, Le Havre in 1866 to one of his famous foggy scenes of Waterloo Bridge in 1903, in which he skilfully captures the thick city air and fleeting interplays of light and colour.

Collecting French Masters, meanwhile, takes a deeper look at the predecessors of Impressionism – from Ingres to Delacroix, Corot and Courbet – and shares their earlier ventures in natural landscapes. One standout is Courbet’s The Ruse, Roe Deer Hunting Episode, (Franche-Comté), 1866 which presents an arresting scene of hunted deer leaping through winter snow.

In the final room, Impressionist Women offers a vital look at the role of women both as artists and subjects during this time. The inclusion of striking portraits by Eva Gonzalès and Berthe Morisot recognises the influence of these important artists and is a reflection of the enlightened approach with which the Hansens curated their collection. Societal constraints often restricted female artists to painting domestic scenes, which meant their subjects were sometimes dismissed as mundane. Yet Morisot’s Young Girl on the Grass, the Red Bodice (Mademoiselle Isabelle Lambert), 1885 shows an engaging contrast of sensitive brushstrokes and lively palette. Meanwhile, Gonzalès’s The Convalescent (Portrait of a Woman in White), 1877-78 is highly expressive and, in deftly mastering the challenges of white paint, clearly demonstrates her skill.

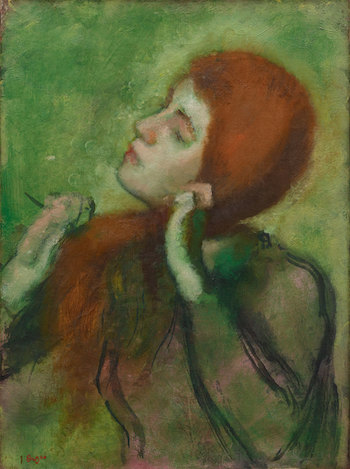

Edgar Degas,

Woman Arranging her Hair (1894). ©Ordrupgaard, Copenhagen. Photo: Anders Sune Berg.

Gauguin’s inimitable style finishes the exhibition and his paintings combine vivid colour, flattened perspectives and elusive subjects to stunning effect. But it is also refreshing that the commentary acknowledges the darker undertones of Gauguin’s life and work, noting the exploitative relationships and colonial narrative present in some of his Polynesian scenes.

With our current environment reducing access to art, this exhibition feels like a particular luxury – even more so for being a formerly private collection which is now public. One especially striking painting is Degas’s Woman Arranging Her Hair. In this intimate portrait, the subject’s flowing red hair blends into an ethereal green background. Degas’s paintings often exude an otherworldly air and this one achieves it to remarkable effect. In carrying the green tints across her hands and clothes, she appears as if underwater, cleansed of any soul-effacing dust. As I leave the exhibition reminded of the transformative effect of art, I feel similarly.

‘Gauguin and the Impressionists’ at the Royal Academy of Arts runs until 18th October 2020. For more information, visit www.royalacademy.org.uk.

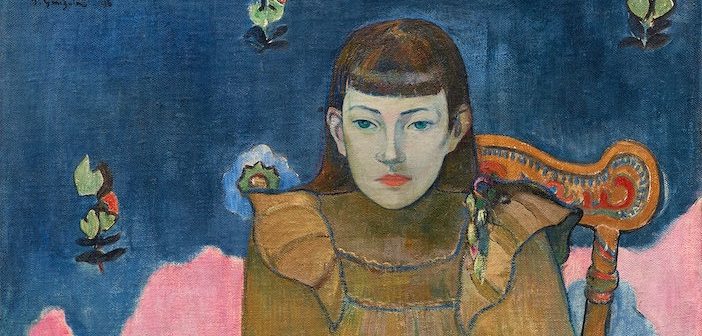

Header image: Paul Gauguin, Portrait of a Young Girl, Vaïte (Jeanne) Goupil (1896), detail.

© Ordrupgaard, Copenhagen. Photo: Anders Sune Berg