Nero’s reputation as a murderous, matricidal despot has prevailed for almost 2,000 years. But was he really the ruthless tyrant history painted him to be? Perhaps not, according to the British Museum’s blockbuster exhibition.

Offering a new angle told through the story of 200 contemporary objects, from the imperial palace in Rome through to Pompeii and Britain, this wide-ranging exhibition challenges the narrative of Nero as a merciless, vain oppressor who subjected the empire to his erratic whims. Instead, it presents the possibility of a different Nero – ‘a populist leader at a time of great change in Roman society’.

Bronze gladiator helmet, Pompei, AD1-100 (courtesy of The British Museum)

Revising history inevitably leaves things in a tangle, though. Particularly when that history is as ancient as Rome’s fifth emperor. Was Nero unfairly villified by his successors in their drive to justify his deposition and death, or does the exhibition fail to present enough evidence to upturn the established tale?

You may not leave decided, but you will certainly leave with rich insight into this intriguing era.

The exhibition’s focus is as much about the power dynamics of the Roman rulers as it is the impressive marble statues and artefacts it collates. It opens with an imposing family tree that takes us through the dysfunctional Julio-Claudian dynasty. We learn how out-of-favour wives were forced to commit suicide, strategic marriages and adoptions were common, and ruthlessness was key to succession. Set within this historical context, Nero’s behaviour doesn’t seem as shocking as it does through the lens of time. Murder, it seems, was quite commonplace.

One of the exhibition’s arguments is that Nero adopted policies that appealed to the people but alienated the elite, which proved to be a dangerous move that defined his reputation. Evidence of the Roman habit of damnatio memoriae – the official suppression of someone’s legacy by defacing or erasing their likeness – lends credence to this.

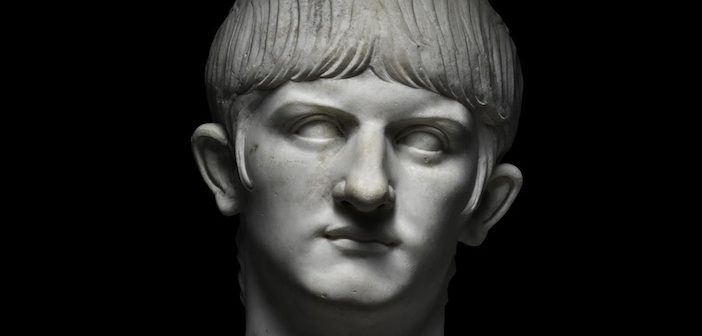

Indeed, there’s a marble portrait of emperor Vespasian which, before it was Vespasian, was actually Nero. Nero’s deep-set eyes remain, but his cultish coiffure was removed. Apparently, such recycling was common. And with four different emperors in the year after Nero’s death, each keen to establish themselves, it’s understandable why little imagery of him remains.

Gilded fresco (AD64-68) from Hall of Achilles in Nero’s Domus Aurea palace (courtesy of The British Museum)

The exhibition’s exploration of propaganda is especially engaging, with an amusing coin series telling of the shift in power between Nero and his mother. Before Nero ascends to emperor, the powerful Agrippina is given prominence on the silver denarius coin, with Nero relegated to the reverse. After his accession, they face each other, but only she is named, presumably an indicator of who was in charge. By AD 55 Nero has become the star of the coin show, with his mother lurking in the background. Not too long after, she disappears from coinage altogether, a warning of things to come.

This is what the exhibition does best, telling big stories through small items and using artefacts to reveal the intricacies of this opaque era. Some of its most evocative items include the hideous, looping chain of neck rings worn by slaves labouring in Wales, the jewellery desperately buried by wealth Romans attempting to flee Boudicca’s strike on Colchester, and a large, warped iron grill from the infamous fire itself.

Iron chains, 100BC-AD78 (image courtesy of National Museum, Wales)

Each of these artefacts brings this ancient history powerfully to life. The question of Nero’s legacy is never fully answered – and may be an impossible quest. But the exhibition’s success lies not only in showing the fragility of history – where the victor gets the last word, but in transporting us into another time, where Nero himself is an engaging seam of a far richer historical tapestry. One where, as this expansive exhibition reveals, there is still far more to learn.

‘Nero: the man behind the myth’ ran at the British Museum until 27th May – 24 October 2021. For more details, including the curator’s virtual tour, and information on forthcoming exhibitions, please visit www.britishmuseum.org.