We are a nation of followers. That’s why we queue. Edward de Bono, the lateral thinker whose life I researched, proposed our brains work in self-organising patterning systems. We are designed to think in a rut, and follow patterns rather than change them. So following others is what we are designed to do.

I thought I was being particularly uncreative by joining that queue on Thursday last week. I had a small bag, a pot of hummus and a forever mug of coffee, and had decided in the moment to go, telling myself it is what we don’t do in life we regret, rather than what we do.

At Waterloo, I asked a man where I should head for. He directed me out of the station to the South Bank and, helpfully, handed me a bottle of water. Then I saw the queue. And, like any other, you follow the line until you reach the end, and you join it.

Photo by Mike Stezycki_(courtesy of Unsplash)

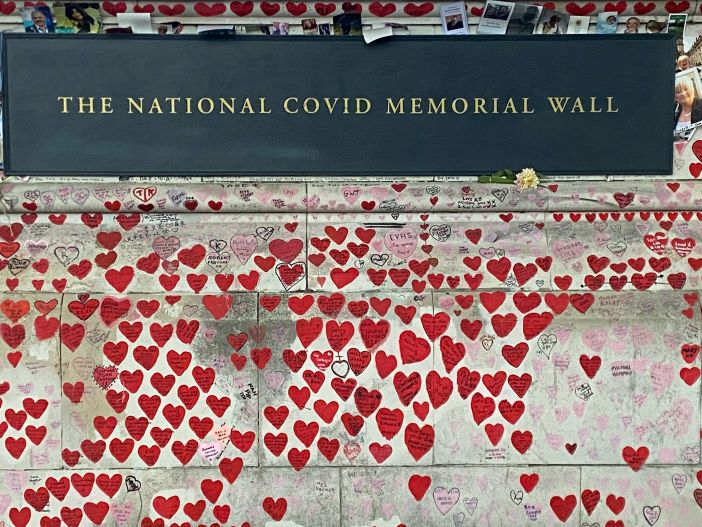

I know the South Bank well. It is one of the best walks in London, as you pass by some of the most glorious landmarks of city. The Tower of London; the Shakespearean Globe; HMS Belfast; the National Theatre, the covid wall (which I didn’t know about); the Houses of Parliament lit at night; the London Dungeon; Hays Galleria; the Royal Festival Hall, and the Dickensian narrow cobbled streets of SE1, where I started my journey. I passed by a road named Elizabeth Walk, realising that’s what this was in many ways. I passed a florist called Heavy Petal with a man gazing at the queue, offering posies of roses and herbs, although everyone seemed to have their flowers already.

Some people were with buggies. Some, like me, travelled alone. The pace was steady and such that it gave time to reflect and contemplate the city in a very different way. Walking slowly in the warm afternoon sunshine (I went on a good weather day, before it turned), I realised London is an incredibly beautiful and fascinating city. Even the Financial sector, which I have always had an antipathy toward, looks a glittering firmament, shining bright in the light. The Shard, the Walkie-Talkie, the Gherkin; nicknames traders would give themselves, albeit with a smattering of expletives.

The docks, with their polished stone alleyways, worn over time by footfall and care; modernised with design studios, cafes and architectural offices. I looked through the windows at workers staring at their iMacs, happy to wave back when I smiled and waved at them.

It was a slow-motion London Marathon, and while I knew the city, venturing there frequently over years, it had been for short, sharp trips and meetings, which I had rushed from to avoid the commuting crowds. This, however, was an opportunity to dwell and observe and breathe in.

I walked past the Globe, which I had visited in my thirties, and the marble statue of the gorilla by David Wynne in Hays Galleria but even more striking were the 28 statues of chimpanzees (in situ until 21 October 2022) in support of endangered animals which, like everything else, shone in autumn light. I didn’t want to lose my place in the queue so didn’t stop to linger further. At HMS Belfast the Queen’s Barge sailed past the queue, practising the route, as the police boats hovered around, like huge black beetles.

Photo by Hulki Okan Tabak (courtesy of Unsplash)

Following others, including two tall men, who once again I found just ahead of me, Ian and Humphrey had decided to join because they were curious. Similarly, like Alice down the rabbit hole, I wanted to know how I would feel, not just seeing Her Majesty in Westminster Hall, but simply standing in line, giving myself time to reflect.

Tower Bridge, Southwark Bridge, London Bridge, all the bridges punctuating the route vied for my attention as I turned to the National Theatre and the Royal Festival Hall, where students were receiving their degrees – cloaked in black for a different reason to everyone else. While some couples didn’t stop talking, others like me were just gazing out at the river, spotting details they had missed before along this South Bank walk.

I thought of many things. The many dates I had a long that same walk. Taking my son to various events along the river as he grew up. The meals at the Oxo Tower when my book was going to be on the billboard in Central Square. I took in the experiences as I was forced to slow down, like some meditative test and walk under Waterloo bridge and towards the Houses of Parliament. Past the London Eye (worth the wait) and London Aquarium (not worth the wait) and walked past the London Council where Witness for the Prosecution was being played. And then onto the walk again along the river, towards Lambeth Bridge, my own Lambeth Walk.

It was becoming noticeably darker and colder and by the time I had reached Westminster Gardens, it was dark. The light pollution up-lit the clouds as spotlights caught the zig-zags of people. As a travel journalist and broadcaster, I’m used to security queues but this was even more challenging than the two hours I shuffled along at Buenos Aires airport in 1997.

The last three hours are the most challenging. I am not sure if the tears that occurred when I turned the corner and saw the coffin were out of relief and tiredness for ending that zig-zag endurance test of over two hundred lanes, or the cumulative grief that rebounded off the white walls – perhaps a combination of both. I felt I had been on a pilgrimage, and the reward of arriving at the palace of Westminster, one which I will not forget. I won’t be able to forget, these moments are, simply, not designed to be forgotten.

I felt a need to curtsy at the coffin. The crown shone like a beacon. My first thought as I turned the corner was that of history. This hall had seen kings and queens of generations live and die, and be judged for treason. The crown is bigger than any single person who wore it, including this Queen. I had never met her, but those who had (including Humphrey and Ian), had thought her grand.

I wept quietly and was held back by the changing of the guard. Granted five more minutes of paying respect, I took in the building, the ceiling, and the cathedral-like grace of the space. It is simple. The rich red of uniforms of the Yeomen of the Guard and Gentlemen at Arms punch out at you, but it is the crown, glittering as it catches the light as you move, that is the most striking.

Two acts made me bite my lip. The first when the guards, carefully, slowly turn their swords upside down, like the hands of a clock passing time, and the synchronicity of which they lowered their heads, ready to awaken and guard the body. The other when the recognition swept over me that the crown is bigger than the person who wears it. I didn’t know the Queen, only the images and PR that were projected onto me since I was a child. I presented a very heavy bouquet to Princess Alexandra who I thought was very tall – I was eight – and asked me my favourite game. ‘Hide and Seek,’ I replied, which everyone around us found funny. I was there as part of an opening of Redbridge Sports Centre, so I should have said tennis or badminton, but I was eight. When asked again, I would still reply Hide and Seek.

So, was it worth it? That journey? That pilgrimage? That psychological endurance test which, I admit, if it hadn’t been for Humphrey and Ian and their banter I would have given up. I am not claustrophobic, but I felt claustrophobia at that final stage. I smiled at the police as we went through the security checks, and they smiled back at me. I thanked all the volunteers and police who I met along the way. Others who had taken the journey the day before cheered us on; others told us ‘you are almost there’. We weren’t ever almost there, even when and especially when I could see and was seemingly in touching distance of Westminster Palace. The cynic in me thinks I cried when I saw the crown out of psychological exhaustion. The romantic in me thinks the crown embodied the hope I felt in my childhood when you learn about kings and queens, and believed in the concept of hope. And fairies.

So, was it worth it? That journey? That pilgrimage? That psychological endurance test which, I admit, if it hadn’t been for Humphrey and Ian and their banter I would have given up. I am not claustrophobic, but I felt claustrophobia at that final stage. I smiled at the police as we went through the security checks, and they smiled back at me. I thanked all the volunteers and police who I met along the way. Others who had taken the journey the day before cheered us on; others told us ‘you are almost there’. We weren’t ever almost there, even when and especially when I could see and was seemingly in touching distance of Westminster Palace. The cynic in me thinks I cried when I saw the crown out of psychological exhaustion. The romantic in me thinks the crown embodied the hope I felt in my childhood when you learn about kings and queens, and believed in the concept of hope. And fairies.

I realised then why I had come. I was curious, like Alice, and chose to go down this rabbit hole. I realise I had been led by the nose by the media. I am not a royalist, nor am I a republican. But I do realise why de Bono was fascinated by the concept of monarchy. He wrote about it in his whimsical, interactive book ‘Why I Want to be King of Australia’ (1991) which he sent to HRH Prince Phillip. I asked him why he wanted to be a King. “Because a King focuses on wisdom, not politics. He has no need for money or needs to impress anyone. He oversees and rises above. He is permanently thinking out of the box, and is not able to be put in one.” This is ironic considering at the end of the 8-hour wait, I was standing in front of one, although no one was ever able to put the Queen in one while she was alive. I felt a sense of history and reverence. I curtsied not because I felt I needed to, or should, but because I wanted to. I was curtseying to the crown, and to the woman who had the strength and ability to wear it.

The journey had been engineered to be endured in quiet and meditation, taking time to observe and take in what is around you. To stand back and watch and listen and choose how to proceed. To come prepared for the long haul or to wing it, as I did, and treat each challenge as an opportunity. Whether to rush ahead, push in, or take the time. To listen to your breath, your thoughts or the banter and noise of others. A bit like how you may live life, really, in a microcosm.

Thank you, ma’am, for the journey.

Photos by the author (unless otherwise noted)