London has a wealth of remarkable exhibitions this autumn but Cezanne at Tate Modern could be the biggest crowd pleaser. In eleven rooms 80 artworks mainly in oils with some watercolours and drawings, plus letters, books, photographs and paintboxes, feed a chronological exploration of how Paul Cezanne, a young French trainee lawyer, studying at the University of Aix, became Cezanne ‘the father of modern art’. The show, which includes rarely loaned masterworks, is a key to how he achieved that accolade. The exhibition curators use the original spelling of Cezanne’s surname without an acute accent, highlighting his Aix-en-Provence roots by reverting to the Provençal way that the artist signed his name.

This exhibition has more than 20 works never publicly shown in the UK, including Still Life with Fruit Dish, 1879-80 on special loan (MoMa, New York); and the phenomenal Mont Saint-Victoire, 1902- 06 (Philadelphia Museum of Art). It is a chance to see rare loans. The artist’s painting materials are on show in the UK for the first time too. If you visited the last Cezanne retrospective 25 years ago – also at Tate – there are works in this collection that you might not have seen. Take a look at the individual owners of the works, written on display labels. It is interesting to see who values Cezanne.

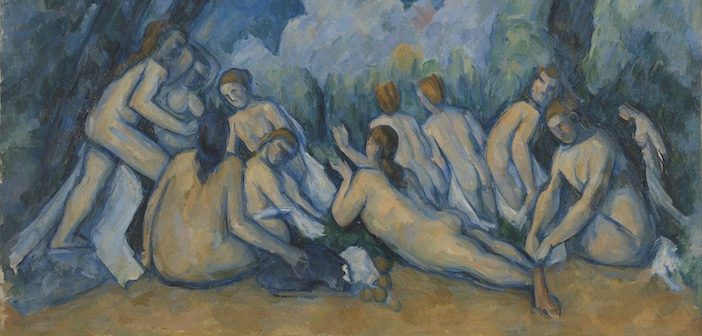

Paul Cezanne – Still Life with Fruit Dish 1879-80. Museum of Modern Art

Paul Cezanne (1839-1906) was born in Aix-en-Provence, southern France. His father, a banker, expected his son to follow law as a profession but Cezanne preferred to train to be a professional artist, against the advice of his family. Travelling between Aix and Paris – on the new train line – allowed him to study art, connect with artist-friends, writers and dealers in the city, then return to Aix to experiment and create works related but unique to his own concept of visual art. He approached painting as a process and an investigation. He coupled the process of making art, in his words, the ‘realisation’ – to his personal experiences, the ‘sensations’. One can see this in his work. Early mentors included the artist Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), and Cezanne’s school friend the author Émile Zola (1840-1902) who encouraged his ambition to be a painter.

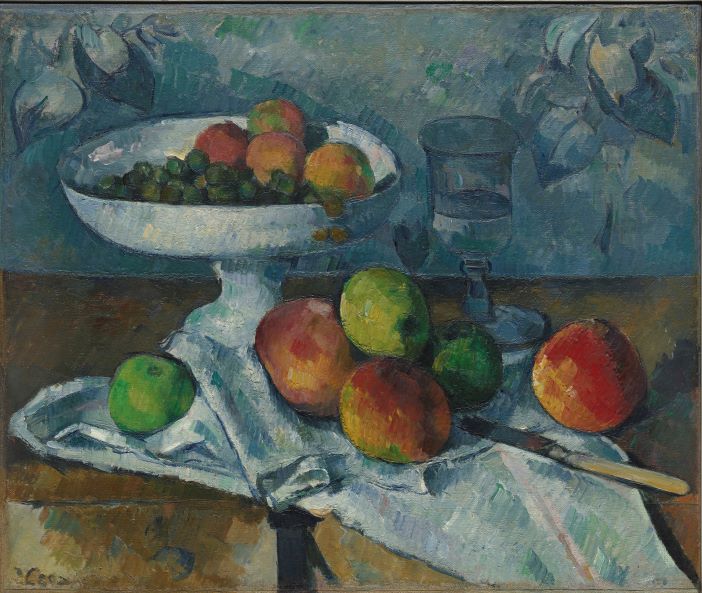

Portrait of the Artist with Pink Background 1875. Paris, Musée d’Orsay. Photo (C) RMN-Grand Palais.

On the third floor of the Tate Turbine building the exhibition opens into a small room with deep blue walls, and introduces Cezanne in a self-appraisal, Self-Portrait of the Artist with a Pink background, 1875 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris). The soft-pink patterned backdrop throws attention on a seated figure with balding head and bushy beard. It is one of many self-portraits Cezanne created, and an insight into how the artist viewed himself. He would have been in his mid-thirties for this portrayal but looks older. His questioning expression sets the tone for a survey of what he achieved during revolutionary changes in the art world; a period that stretched beyond formal academic art to post-impressionism by the time of his death in 1906. In this room too is The Basket of Apples, 1893 (The Art Institute of Chicago), with its leaning bottle of wine, an exemplar of the still life works for which he is revered.

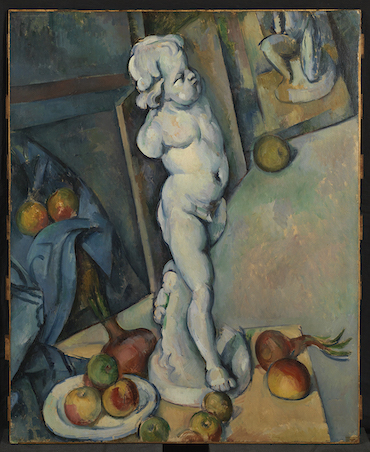

The show follows a chronological outline, and worth studying in the second room is the small early work, an impasto, Sugar Bowl, Pears and Blue Cup, 1865-70 (Musée-Granet, Aix-en-Provence). A dark background highlights the citrus sharp colours of objects and thick paint layered on with a palette knife. Unanticipated inclusions like The Murder 1866-70 (Walker Art Gallery, National Museums, Liverpool), a dark scene of a brutal killing, may have been a response to Zola’s 1868 novel Therese Raquin featuring a deadly love triangle. Study of these dark, early pieces lead on to the radical change in Cezanne’s painting technique, under the influence of Pissarro, while beginning an uncertain career living on an allowance from his father. In this show there is an early Bathers, 1874-75 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) in the first half of the exhibition, a pre-model of the larger-canvas bathers’ series for which Cezanne is famous – with one, Bathers, 1894-1905 (The National Gallery, London) created twenty years later, exhibited toward the end of the exhibition. Tate editorial states that to aid their own practice, artists have purchased more copies of Cezanne’s ‘bather’ works than any other subject.

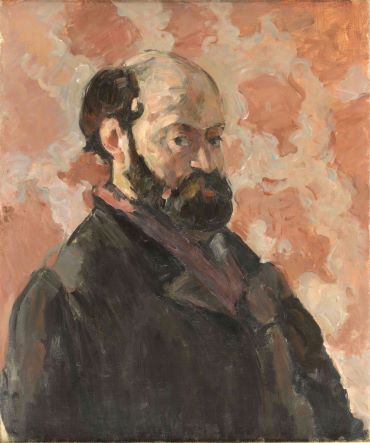

Still Life with Plaster Cupid. The Courtauld, London.

In this retrospective one can see Cezanne exploring the wide possibilities of painting what he saw combined with the sensation of it. He said, ‘I paint as I see, as I feel’. It is evident in the tender portrayal of his young son Paul (born 1872) in Portrait of the Artist’s Son, 1881-82 (Musée de L’Orangerie, Paris). And, in portraits of his partner and lifelong companion, Marie-Hortense Fiquet (1850-1922), the mother of Paul, whom he married in 1886. There are twenty-nine known portraits of Madame Cezanne. His painting objectives are evident too in the still life works. Eight of these, all painted in his studio in Aix-en-Provence 1893-95, and gathered from galleries around the world, have been reunited for the first time. Cezanne stated ‘With an apple I will astonish Paris’. He was true to his words, apparent in Still Life with Plaster Cupid c.1894 (The Courtauld, London) – one of two versions displayed, the other from The National Museum, Stockholm – which show Cezanne ignoring the constraints of realism, using apples to play with perspective.

1899-1906 was a period of uncertainty for Cezanne. Following the death of his mother in 1897, the Provence country estate Jas de Bouffan, bought by his father in 1859, and inherited by Cezanne, his mother and sisters, on the death of his father in 1886, was sold. Cezanne, diagnosed with diabetes, and getting weaker, sold the artworks in his Paris studio to his dealer Ambroise Vollard (1866-1939) and built a new studio in Les Lauves, Aix en Provence. Here his innovative experimentation included luminous watercolours and painting en-plein-air, focusing on landscapes more than people. The exhibition explores this changing phase of his life.

Seated Man (1905)

© Museo Nacional Thyssen, Bornemisza, Madrid

The final room 1899-1906 is perhaps the most enthralling. The compilation of works reveal how Cezanne had continuously experimented, pushing at boundaries of perception. Here one can closely study his brushwork in the build-up of colour and form, layer upon layer in blocks of colour of differing shapes and size. He plays with light and shade, creating from a first impression the finished work. One sees this in depictions of Mont Saint-Victoire, in views of L’Estaque. In Seated Man, 1905-06 (Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid) – there is a preliminary drawing next to the painting – Cezanne’s build-up of warm colour blocks with thick brushwork, reveals the intensely felt visual presence of Vallier, Cezanne’s gardener and odd-job man. In this room the tag ‘father of modern art’ is understood. Claude Monet (1850-1926) called Cezanne ‘the greatest of us all’.

Paul Cezanne absorbed the differing factions of contemporary art of his time but was influenced only by his own understanding of what he saw and sensed, accomplished through continuous practise. In many of the artworks in this show we see the origins of later artworks by artists that followed him, including Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) and Georges Braque (1882-1963) both young painters at the time of Cezanne’s death in 1906, and hugely influenced by his work. And, like Picasso and Braque and the many artists who flocked to see the Cezanne retrospective at the Salon d’Automne in Paris in 1907, this current Tate retrospective of Paul Cezanne’s art and life is not to be missed.

The EY Exhibition: CEZANNE runs at Tate Modern, Bankside until 12 March 2023. Open 10-6pm Monday to Sunday. Tickets: £22.00 plus concessions available/free for Tate members. For more information, visit www.tate.org.uk.

Header image: Paul Cezanne – Bathers (detail) c.1894-1905. Presented by the National Gallery, purchased with a special grant and the aid of the Max Rayne Foundation, 1964.