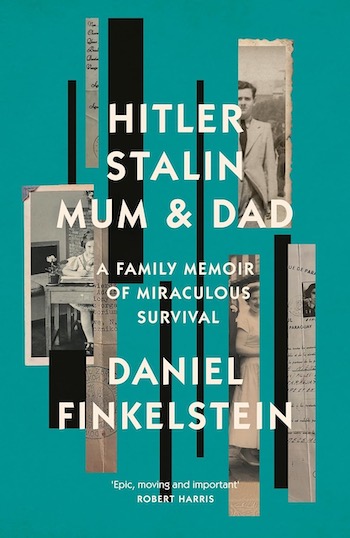

Daniel Finkelstein, probably best known for his political and football journalism in The Times, has now written a remarkable and deeply moving memoir about how his mother (a German Jew) and his father (a Polish Jew) somehow managed to survive the horrors inflicted by the Germans and the Russians during the Second World War. It is not a surprise that the BBC has chosen it as one of its Books of the Week. While written and published before the recent outbreak of shocking violence in the Middle East precipitated by the massacres carried out by Hamas, it nonetheless provides a relevant backdrop to and partial explanation of the reactions and responses both of individual Israelis and of the Israeli state.

The book is a labour of love that pays well-deserved tribute not just to his parents but also to his grandparents who made their survival possible. That any of them survived when the majority of those around them did not was partly down to luck but mostly to a combination of bloody-minded determination, resourcefulness, and courage. However, this is no hagiography. Remarkable people though they all clearly are, they emerge, nonetheless, from the pages with their own individual foibles, strengths, and weaknesses.

The book is a labour of love that pays well-deserved tribute not just to his parents but also to his grandparents who made their survival possible. That any of them survived when the majority of those around them did not was partly down to luck but mostly to a combination of bloody-minded determination, resourcefulness, and courage. However, this is no hagiography. Remarkable people though they all clearly are, they emerge, nonetheless, from the pages with their own individual foibles, strengths, and weaknesses.

The book tells three different stories. There is the story of Daniel’s grandfather Alfred Weiner, founder of the world-famous Weiner Library, who moved with his family to Holland to escape Nazi persecution only to became separated from them when the Germans invaded while he was in England. There is then the story of the relentless struggle of Alfred’s wife Margarete and their three daughters, one of whom, Mirjam, became Daniel Finkelstein’s mother, to survive the Nazi occupation of Holland and their subsequent incarceration in the Westerbork and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps. The third story is that of the struggles of Finkelstein’s Polish grandparents, Dolu and Lusia and their son Ludwik, his father, to survive the deportation of so many Poles to the Siberian and Kazakh gulag in the aftermath of the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939.

The Wieners had emigrated to Holland in 1934 to escape the Nazis as did so many other Jews. Alfred Weiner was a well-known member of the Jewish German community who had set up an organisation to monitor Nazi and other anti-semitic activity. The plan was to use the safety of Holland to provide the base needed to carry on his monitoring of Nazi activities. However, in 1939 Alfred had to move the archive to London. The Dutch government was pressurising him as they were increasingly concerned about upsetting the Germans. This move was the start of what eventually became the Weiner Library. During the war Alfred’s archive provided an invaluable source of information about the Nazis which was used by both UK and US government agencies. For the family the move turned into a tragedy as the Germans invaded Holland before Alfred could get his wife and children to London.

Photo by Nick Scheerbart (courtesy of Unsplash)

So began the struggle for survival endured by Finkelstein’s grandmother, his mother and her two sisters. Their experience in Amsterdam under Nazi rule and then in Westerbork and finally Bergen-Belsen was no different to that endured by thousands of other Jews in Holland. What was different was the relentless determination of Margarete that her daughters should survive and the fact that she succeeded when so many others failed. Her success was down to three main reasons: firstly, because she managed to keep all four of them positive and reasonably healthy; secondly, because through contacts they managed to obtain the Paraguayan passports being organised clandestinely by the Aleksander Lados group in Switzerland; thirdly, the luck that the Nazis were prepared to agree to a prisoner exchange. Survival was always touch and go at every stage. It only became certain once they had crossed the Swiss border. Even then tragedy was to strike.

Finkelstein’s Polish father and grandparents were citizens of the Polish city of Lvov (now the Ukrainian city of Lviv) that was taken over by the Soviets in 1939. His grandfather, Dolu, a successful businessman, was lucky not to have been shot by the Russians along with the 22,000 victims of the Katyn Massacre. Instead, he disappeared into the Soviet prison system. His wife Lusia (Finkelstein’s grandmother) and son Ludwik (Finkelstein’s father) were deported along with over a million other Poles to Siberia and Kazakhstan, in their case to the latter. How they managed to survive the bitter winters of the Kazakhstan steppe without decent food, clothing and shelter is extraordinary. At least half of those deported died. How Lusia outwitted the paranoid bureaucracy is a wonderful lesson in knowing your enemy and exploiting their weaknesses.

Lviv (photo by Dima Pima, courtesy of Unsplash)

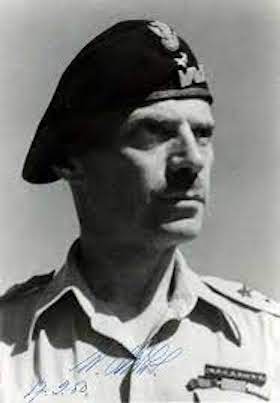

Equally extraordinary is the story of how they were reunited with Dolu, now a member of a Polish Army created at the behest of Stalin from the Polish deportees. They were placed under the command of General Anders, a senior member of the pre-war Polish Army, who had somehow escaped being one of the victims of the Katyn Massacre. Along with the army gradually built by Anders, Dolu, Luisa and Ludwik found themselves, thankfully, crossing the Caspian Sea to Iran and becoming part of the British war effort. Stalin had decided he could no longer afford the resources this new organisation needed to become battle ready, especially when he doubted their loyalty.

Władysław Anders (1892-1970), General of the Polish Army

One of the strengths of Finkelstein’s book is the way that he weaves the travails of his family into the wider context of the war and of the Holocaust. In doing so he illuminates lesser-known aspects of both. This is particularly true of the impact of the treatment of the Poles by the Russians following the Nazi-Soviet Pact, the impact of the Nazi occupation of Holland on its citizens and especially its Jewish citizens and the story of the Paraguayan passports and visas. Finkelstein also gives due recognition to outstanding individuals whose contribution deserves to be better known such as General Anders and Aleksander Lados to name but two. He brings all his characters to life, good, bad, fearful or courageous. He also captures the atmosphere of desperation, paranoia and self-deception that always threatened to envelop those trapped by the Nazi and Soviet tyrannies, in their prison camps and faced with the mindless bureaucracies that accompanied them.

There is also a profound message to be found in this moving and wonderful book. It is encapsulated in Finkelstein’s description of his parents’ response to the horrors that they and their families endured at the equally appalling hands of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia and by his mother in one succinct sentence. For Finkelstein: “While they had the right to act as victims, it wasn’t a right they were going to exercise… What they did, instead, was to transcend what happened to them… They were determined that we wouldn’t just exist, we would live.” When asked once how she would like to be described his mother’s response was “I think of myself as a person, a wife and mother first, and a survivor last.” In the narcissistic age we live in, an age seemingly obsessed with victimhood, where so many seem desperate to find a badge of victimhood they can wear, it is a message worth remembering.

‘Hitler, Stalin Mum and Dad: A Memoir of Survival’ by Daniel Finkelstein is available now, published by Harper Collins. Daniel’s podcast is currently available on BBC Sounds.

For more information about Holocaust Memorial Day, including details of ceremonies, activities and news, please visit www.hmd.org.uk.

Header image by Tatiana Rodriguez (courtesy of Unsplash)