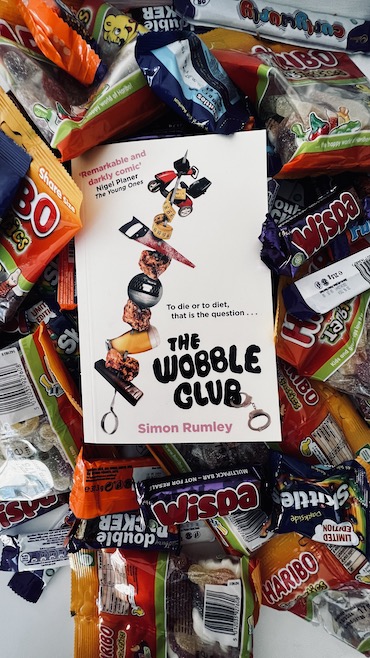

Auteur filmmaker, scriptwriter and Arb contributor Simon Rumley’s first novel is at times an unsettling read, but there’s more to it than meets the cover, says Harry Chapman…

I approached The Wobble Club with a certain degree of apprehension. At three hundred and ninety-nine pages it didn’t possess the girth of a Don Quixote or a War and Peace, but it wasn’t exactly slimline. But if I was going to be completely honest, it wasn’t the size of the book that worried me, it was the size of its protagonists – did I really want to spend a month in the company of a couple who are morbidly obese? Which begged the second and more important question – in a society where we are expected to be accepting of peoples’ differences, was I, in fact, a closet fattist? Is prejudice against people who are overweight the last bastion of intolerance?

Gill and Brolly, who live off the Walworth Road in South London where most of the action unfolds, are not merely overweight, but vast by any standards. At the start of the tale Brolly weighs in at an impressive forty-two stone (that’s three fourteen stone men rolled into one) and Gill is only just behind on the scales. They live in a house adapted for their needs with stairlift and double sized bathroom, and sleep in separate rooms as no double bed could withstand the force of their combined weight. The opening describes the sheer labour of moving such bulk around on a relatively spindly frame;

Gill and Brolly, who live off the Walworth Road in South London where most of the action unfolds, are not merely overweight, but vast by any standards. At the start of the tale Brolly weighs in at an impressive forty-two stone (that’s three fourteen stone men rolled into one) and Gill is only just behind on the scales. They live in a house adapted for their needs with stairlift and double sized bathroom, and sleep in separate rooms as no double bed could withstand the force of their combined weight. The opening describes the sheer labour of moving such bulk around on a relatively spindly frame;

“His heart pounded and his lungs flapped. He squeezed his legs together and, like an oversized testicle, cupped his stomach from below…opened his legs…leaned forward…he let it slip inch by inch to the floor.”

What propels us into the story is Brolly’s decision to go on a diet coming into collision with Gill’s determination to go on living as if there is no price to be paid. Brolly’s resolution is partly born out of an internal urge and partly a response to the demise of their good friend Tiny Tim, who, like the couple, is severely obese, but twenty years older, succumbs to the effects of type two diabetes, gangrene, amputation and finally, death. The novel withholds judgement but these three characters represent the broad approaches to living with extreme weight: Tiny Tim skips down the road of excess merrily to an early grave, Gill lives in total denial of the mounting risks and Brolly decides to stop and do something about it.

The narrative focus switches between the two main characters and is so deft that one becomes complicit in Gill’s betrayals as one is achingly sympathetic of Brolly’s desire to do the right thing. So full blooded are they that it is only towards the end that I realise that, yes, it is Brolly’s story. It is he who drives the narrative and despite Gill’s complexity, it is only he that undergoes real change and who has the strength of character to change.

Around them is a rogue’s gallery of grotesques and oddballs. At Harry’s Hardware Store, which Gill manages, her staff of Dagmara, Gay Keith and Potatohead are despatched as flashes of eccentric colour. With the likes of Taxi Rob, Landlady Kim and Blue-Eyed Pete, we get to delve deeper, usually with a Freudian vignette that helps to illuminate some particular sexual predilection or eating perversion. It is not only Gill and Brolly who wallow in these waters, the twin human motivators of sex and eating run through these pages like a chocolate smeared streaker at a vegan church fete.

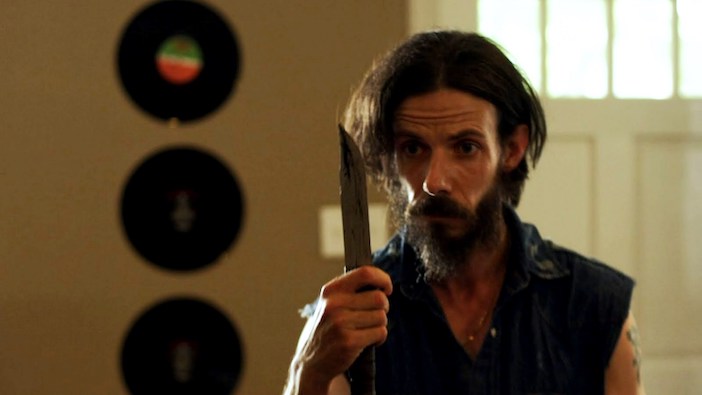

Noah Taylor as psychopath Nate in ‘Red, White & Blue’ (2010)

It is no coincidence that these illustrated snatches of back story are reminiscent of film flash backs because Mr Rumley, by trade, is a film maker. He has written and directed nine films over the past twenty odd years, with a hand in two more, in a variety of genres but many standing firmly in the canon of horror. In fact, his film Red, White and Blue has the distinction of being the only film since Alien (which I first saw on its release at the age of eight) where I have had to cover my eyes in, well, horror. Like his films the book canters through a range of, not exactly genres, but more zones of feeling, much in the way life unfolds. The world though is very much entrenched in the marginal – also like his films – that of society’s soft, white underbelly, no pun intended.

Rumley constructs sentences with the same aberrant relish that he does shots in a film sequence. Occasionally the prolixity and superabundance of imagery sinks itself but generally it all hangs together in a consistent style which is at once anachronistic and modern. Scenes of marvellous deformity balance one on top of the other. Favourites include Gill’s out-of-body trip to a gym where the denizens are so different that they begin to resemble a separate species – and Brolly’s origin story at the hand of schoolyard Satan McManus who catapults his charge along the desolate road of eating for entertainment and self-worth. In the third act there is a very definite gear shift into unabashed horror where the slow turns of the screw are both unexpected and horribly satisfying.

The Wobble Club (and yes, there is a club of that name that gets a glorious unveiling towards the end) is, by turns, comic, obscene, brutal, tender and moving. Its greatest triumph though is taking two characters that in other circumstances might have been reduced to the level of carnival freaks and treating them with dignity and a true generosity of spirit.

All of which begs the question – could Simon Rumley be the b*stard love child of Irvine Welsh and Charles Bukowski?

The Wobble Club is available online and in specialist stockists. For more information, including details of Simon’s filmography, visit www.simonrumley.com.