Dame Elisabeth Frink, one of Britain’s most important post-war sculptors, and arguably its greatest female sculptor, died on April 18th, 1993, in Dorset. This year, on the thirtieth anniversary of her death, Dorset Museum and Art Gallery in Dorchester are presenting ‘Elisabeth Frink: A View From Within’, the museum’s first-ever exhibition to focus on Frink’s life and work in Dorset.

In 1976, visiting friends in Sherborne with her husband Alex, Frink happened across a neglected, secluded house for sale. She had lived in Dorset as a child from the age of 11 when her father, an army officer, was stationed in the county. She loved the Dorset landscape, and this house she saw, and its spacious grounds – provided the perfect site for her large-scale works, and the light essential for her work, as well as land to keep horses.

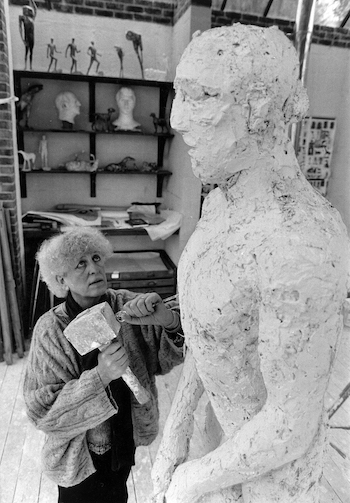

Elisabeth Frink working on the Dorset Martyr group, 1985 (Photo © Anthony Marshall/Courtesy of Dorset History Centre)

Thus, it was Woolland House, near Blandford Forum – around ten miles from Dorchester – which became her home and studio for sixteen years from 1976 until her death in 1993. She lived here with her third husband Alex Csáky, and her artist-son Lin Jammet, by her first marriage to architect Michael Jammet. The vast, light-filled studio was designed by Csaky’s son John, and many of her most famous works were created in her Dorset studio.

It was here that she made a significant historic work for Dorset. Three over-life-size bronze statues, the ‘Dorset Martyrs’, were created with two of the three representing the innumerable number of Dorset’s religious martyrs of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, executed for their faith. In 1986 the work was placed on Gallows Hill in Dorchester, where executions had taken place. A photograph taken of Frink, at work on a ‘martyr’ in her studio, highlights the monumental size of the figures. Frink modelled with wet plaster on metal rods and wires, using strips of various materials to twist the plaster around the metal framework. The shape of the sculpture was created by chiselling the surface when nearly dried out. This wet plaster process was repeated until the desired shape was achieved and the plaster model prepared for bronze casting.

In 1973, Elisabeth Frink was the first female sculptor to be elected as a Royal Academician. She was created a Dame in 1982 and is one of the most celebrated sculptors of the twentieth century. Frink is noted for timeless sculptures and prints of horses, cats, dogs, birds, and humans, which could be seen as a snapshot of her everyday life in Dorset. Her work was inspired by figurative sculptors such as Alberto Giacometti, August Rodin, and Cézar Baldaccini.

Standing Horse, 1993 (Dorset Museum collection)

She succeeded with figurative sculpture at a time when abstract sculpture, as seen in works by British sculptor Anthony Caro, noted for metal assemblage pieces, was in greater demand. Figuratively, Frink’s human sculptures are primarily male, often a lone male, or a male head. There is a life-size female statue in the Dorset Museum exhibition, ‘Walking Madonna’ (1981), a solitary, striding figure, created for the grounds of Salisbury Cathedral, but the female body as a subject was not of prime interest to Frink, preferring the male form, or non-human forms.

On her death, Woolland house and studio, and all materials, were inherited by her son. Then, on his death in 2017, all her works – through the Elisabeth Frink Estate and Archive – were given to the nation through bequests to twelve museums in Britain, including the British Museum, making her work accessible to a wide audience. In 2020, one of the largest beneficiaries, a bequest of almost 400 works, including 31 bronze sculptures by Frink, was Dorset Museum.

Now with ownership secured, 80 sculptures, drawings and prints by Frink are on display in the museum’s exhibition ‘Elisabeth Frink: A View From Within’ which includes working plasters – monumental in size – created for bronze sculptures that have never been exhibited before. They are informed by the ancient Greek ‘Riace’ bronze warrior figures, c 460-450 BC, recovered off the coast of Calabria, southern Italy in 1972. Frink’s ‘Riace’ are perhaps modern-day mercenaries wearing white masks, linking ancient histories to the present day. Here too in the exhibition is a remarkable model of ‘Risen Christ’ (1993), her final monumental bronze, erected above the West Doors of Liverpool Cathedral in the year she died.

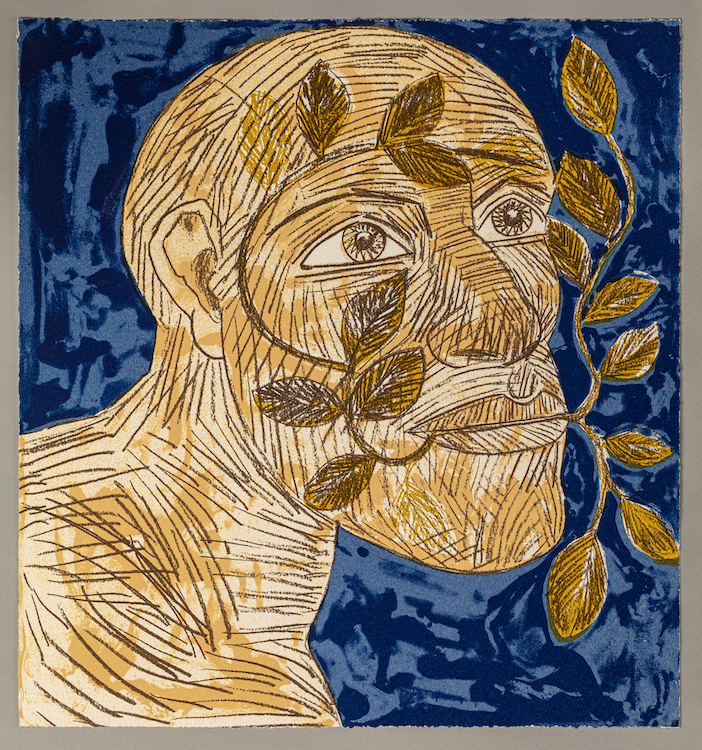

Green Man (Blue), 1992 (Dorset Museum collection)

At Woolland House, Frink kept dogs and cats, chickens and horses. She had grown up with horses and her husband, a businessman, was a racehorse owner. Her horse sculptures and drawings explore the ‘horsiness’ of horses with their distinctive characteristics, such as the solidity of ‘Standing Horse’, one of her last works. Outstanding sculptures in the exhibition, of animals and birds, including her cockerel in bronze, and a remarkable owl in print, reveal her closeness to nature, animals and wildlife. Csáky’s Hungarian gundogs are on display too, their distinctive features captured by Frink. Green Man (Blue), one in a series of screenprints, also stands out. She created the series after reading a book Green Man: The Archetype of Our Oneness with the Earth,1990, by William Anderson. Frink read it in hospital whilst undergoing treatment for cancer in 1992. Green Man (Blue) portrays human vulnerability.

Thirty years after her death, Frink’s legacy is the gift of her remarkable works to the nation.

‘Elisabeth Frink: A View From Within’ runs until 21st April 2024 at the Dorset Museum and Art Gallery, High West Street, Dorchester DT1 1XA. For more information, please visit www.dorsetmuseum.org.