Peter Moore’s most recent book was not written with the United States election in mind but it does provide interesting historical background to the establishment of the American Republic and, not least, given the divisions evident, that politics could be as savage and divisive as anything today. The title of the book – Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness: Britain and the American Dream – might give the impression that Moore has written a dry academic tome of political philosophy.

Nothing could be further from the truth. This is a highly readable book mostly focused on six very different characters, the world they lived in and how their ideas, arguments, actions and, sometimes, relationships not only played a part in the vibrant political debates that were taking place in London but also had an impact across the Atlantic. In doing so Moore seeks to explain how political events and debates in Britain helped ignite the political fires that resulted in the American Revolution and also provided the political ideas that inspired the Declaration of Independence as well as Jefferson’s memorable phrase, ‘Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’.

At the same time Moore manages brilliantly to recreate the rumbustious energy, adventurous spirit and dedication to free debate and intellectual inquiry that filled the air in Britain, and soon found its way across the Atlantic. This was, after all, Britain in the Age of Enlightenment, when old certainties were being challenged and new ideas widely circulated. The picture he paints not only provides a vivid contrast to the censorious times we are currently living through – 18th century political cartoons frequently make their 21st century successors seem very tame – but also an illuminating historical context to some of the debates that have provided material for news and social media during the current American election, especially now that the traditional view of ‘Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’ has become bitterly contested territory.

At the same time Moore manages brilliantly to recreate the rumbustious energy, adventurous spirit and dedication to free debate and intellectual inquiry that filled the air in Britain, and soon found its way across the Atlantic. This was, after all, Britain in the Age of Enlightenment, when old certainties were being challenged and new ideas widely circulated. The picture he paints not only provides a vivid contrast to the censorious times we are currently living through – 18th century political cartoons frequently make their 21st century successors seem very tame – but also an illuminating historical context to some of the debates that have provided material for news and social media during the current American election, especially now that the traditional view of ‘Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’ has become bitterly contested territory.

Moore provides a colourful collection of characters to illustrate his arguments. Foremost among them is Benjamin Franklin. One of the Founding Fathers, Franklin emerges from the pages as a supreme example of what became the American Dream. He was a self-made man with a wry wit and down-to-earth wisdom, both of which were on show in Poor Richard’s Almanack, which he published every year from 1733 to 1758. Franklin started his working life as a printer before becoming a journalist, businessman, author, politician, scientist, inventor, diplomat and the oldest member of the committee of five tasked with drafting the Declaration of Independence.

Moore’s supporting cast are a fascinating and varied group. The best known is the curmudgeonly and sharp-witted Dr Samuel Johnson who, when confronted with the complaints of the colonists, commented “how is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty from the drivers of negroes?”. Following close behind is the radical thinker and polemicist Tom Paine, whose pamphlet Common Sense arguing for the Thirteen Colonies to set up an independent republic had an incendiary impact. There is then the waspish John Wilkes, notorious rake and radical journalist who mobilised popular support on the street – ‘politics out of doors’ as it was called – and helped free the press from censorship before becoming an MP and Lord Mayor of London.

Catherine Macaulay by Robert Edge Pine (National Portrait Gallery)

Far more respectable, certainly more academic, but rather more genuinely radical when it came to political theory was Catherine Macaulay, a dedicated republican, an early advocate of parliamentary reform and a supporter of John Wilkes, she was also the first female historian. Her major work was an eight-volume history of English politics in the 17th Century. Her significance for Moore is as a transatlantic conduit for republican ideas through her correspondence with John and Abigail Adams – the Adams who was one of the Founding Fathers and the second President of the new American Republic. William Strahan, the last of Moore’s group is the least well known but important in Moore’s story also because of his publishing, political and transatlantic links. Strahan started life in Edinburgh but moved to London where he became one of the most successful printers and publishers in Britain and an MP with the resulting political connections. His publishing client list included four of the most influential writers of the 18th Century – Samuel Johnson, David Hume, Adam Smith and Edward Gibbon. Strahan was also correspondent, friend and occasional business partner with Benjamin Franklin who printed American editions of some of his books.

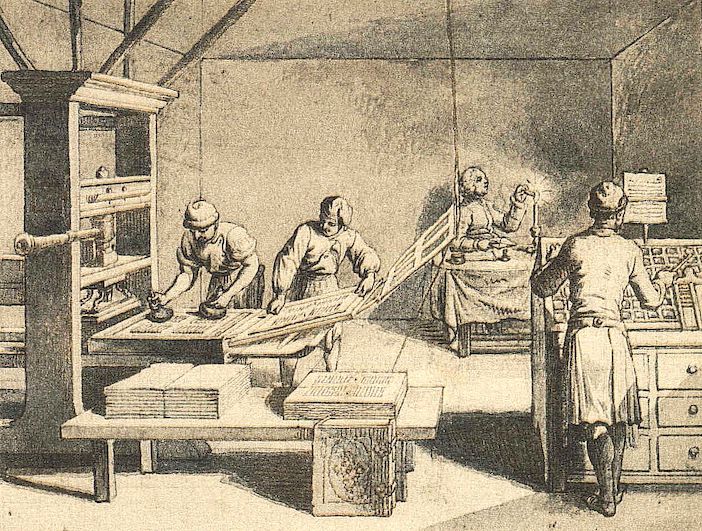

An equally, if not more important, character in Moore’s story is the printed page. Even though the technology of printing did not change much during 18th Century there was nonetheless a dramatic upsurge in the demand for novels, news and information of all kinds. Demand was driven partly by the spread of literacy and partly by the increasing democratisation of public discourse. It was not just provided by an increase in the publication of books but also through a wide range of different and sometimes new types of publication such as daily, weekly or monthly newspapers, pamphlets, fliers and magazines. The information these provided ranged from the serious to the frivolous and scandalous, from politics to geography (it was the age of Captain Cook and de Bougainville), from finance and commerce to housekeeping and fashion (the Spectator and the Tatler were amongst the early starters). It is also not a coincidence that two of Moore’s principal characters, Benjamin Franklin and William Strahan were publishers and that all of the others were active writers.

Printing press circa 1770 (image courtesy of Wikipedia)

Central to Moore’s narrative is the impact of the transatlantic transmission of political ideas via the printed page as a result of the intellectual and commercial relationships he explores. There is no doubt that the Thirteen Colonies saw the same upsurge of the written and printed word as did Britain. Benjamin Franklin’s home city of Philadelphia had a single printing house in the 1680s. By the 1770s there were almost fifty. Indeed, as early as 1789, David Ramsay, an early American historian, was able to write in his History of the American Revolution that, “in establishing American independence, the pen and press had merit equal to that of the sword”. No better evidence for this can be found than in the publishing history and political impact of the English radical Tom Paine’s pamphlet ‘Common Sense’ . It was as Moore makes clear in some detail the document that did most to fan the flickering flames of the movement for independence and turn them into a raging fire. First published in January 1776 it went through some twenty-five editions with over half a million copies printed within the year. This when the population of the Thirteen Colonies was a modest two and a half million.

As the principal author of the Declaration of Independence it is somewhat surprising, at first sight, how few pages Moore gives to Jefferson especially as Jefferson had imbibed so much from so many seminal figures of the European Enlightenment. He was a huge admirer of both Locke and Newton, had devoured the writings of Johnson, Hume and Montesquieu and as a lawyer by training was aware of the work of the influential British jurist William Blackstone. That said, Moore does focus far more on the origins of Jefferson’s most famous phrase – Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness. In particular, Moore draws attention to the intellectual influence of Samuel Johnson especially in the context of the Pursuit of Happiness and the 18th Century discourse as to what was meant by happiness and how it could be achieved. As Moore points out, even if Johnson and Jefferson did not often agree on politics they were in agreement that while people might have an inalienable right to pursue happiness no one could necessarily expect to find it.

The objectives of Moore’s book are to qualify the exceptionalism of the American Dream by placing it in the wider context of the Enlightenment and most especially the British elements from which it sprang. He certainly succeeds in his task by illuminating some of the personal links that crossed the Atlantic and the webs of thought that came with them. Most important of all, he shows how the language of the legal, political and constitutional debates in London not only came to dominate debate in the Thirteen Colonies but also turned into practical politics and fuelled what became the American Revolution. Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness had become the basis for a new republic. It all makes for a stimulating read, not least given the current divisions in American society, the attacks on the Founding Fathers, the attempts to undermine the political inheritance of the new republic they created and the deep divisions exposed during the current election.

Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness by Peter Moore is out now in hardback, paperback, ebook and audio, published by Chatto & Windus. For more information, please visit www.penguin.co.uk.

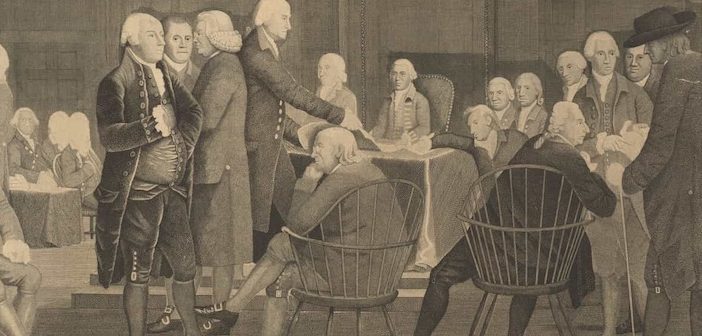

Header image: The Second Continental Congress, the Declaration of Independence,

by Edward Savage (1761-1817), National Gallery of Art, Washington DC