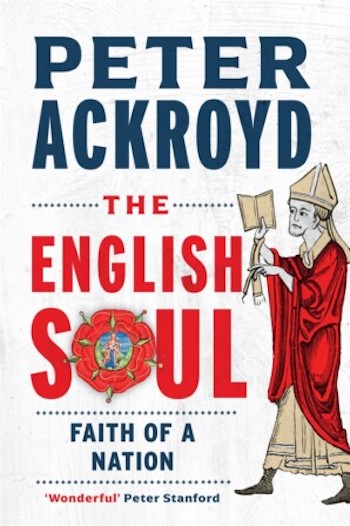

Peter Ackroyd is a prolific writer, having published over sixty-five books as poet, novelist, biographer and cultural historian. At the heart of his writing, whether fiction or non-fiction, are the culture and history of England, and of London in particular. His most recent book, The English Soul, is essentially a wide-ranging survey of the development of the Christianity in England. He drives his narrative via a series of mini biographies of significant religious figures. They include individuals both clerical and lay, conformist and non-conformist, radical and conservative, theological and political, literary and missionary. He begins the chronological start of his journey with a chapter on the Venerable Bede and ends it with a brief paragraph on Archbishop Welby, albeit not in his final chapter.

Given the number of biographies he has written, of which those of Thomas More, Blake and Dickens are probably the best, it is perhaps unsurprising that he has chosen a biographical approach. It does however bring with it some unevenness of coverage, the most obvious being his six-century jump from Bede in the late 7th and early 8th centuries to Julian of Norwich and John Wyclif in the 14th Century. In doing so, he misses out the religious impact of the Norman Conquest. It opened the door to the building of so many of our great cathedrals and their long-lasting visual and cultural impact; also, to the monastic revival that had so much social as well as religious importance until the Reformation; and, to the growth of the widespread habit of pilgrimage of which the most popular in England is celebrated in the Canterbury Tales of Geoffrey Chaucer.

Given the number of biographies he has written, of which those of Thomas More, Blake and Dickens are probably the best, it is perhaps unsurprising that he has chosen a biographical approach. It does however bring with it some unevenness of coverage, the most obvious being his six-century jump from Bede in the late 7th and early 8th centuries to Julian of Norwich and John Wyclif in the 14th Century. In doing so, he misses out the religious impact of the Norman Conquest. It opened the door to the building of so many of our great cathedrals and their long-lasting visual and cultural impact; also, to the monastic revival that had so much social as well as religious importance until the Reformation; and, to the growth of the widespread habit of pilgrimage of which the most popular in England is celebrated in the Canterbury Tales of Geoffrey Chaucer.

Central to Ackroyd’s story is his belief in Christianity in all its varieties as the ‘anchoring and defining doctrine of England’. It is a very English story that he tells as he pays no attention to the Christian story in the rest of the British Isles or to that of any other religions. On reaching the end of the book it becomes clear that what Ackroyd has written is, in part, whether intentional or unintentional is unclear, an elegy for an England and an English Christian soul that is fast disappearing. The England of his story is not the increasingly multi-ethnic, multi-cultural, secular country of today, struggling to work out and come to terms with a new identity.

The Venerable Bede writing the Ecclesiastical History of the English People (from a 12th-century codex at Engelberg Abbey, Switzerland. Image courtesy of Creative Commons)

He begins his English story by arguing that Bede first coined the idea of an English identity when he wrote about the Angli in reference to the inhabitants of a Kingdom of England that did not yet exist. It was not a name invented by Bede. The Angles were one of the Germanic tribes that had settled in England almost 200 years before Bede was born and about whom the apocryphal story of Pope Gregory’s description of a group of young fair-haired Angle slaves in Rome as non angli sed angeli (not Angles, but angels) is told. Ackroyd’s argument is perhaps a bit of a stretch given it was to be almost another 200 years after the death of Bede that Athelstan was acknowledged as the first king of all the English.

Ackroyd is at his strongest and most comfortable when dealing with the English Reformation and the theological and political struggles that followed until the Glorious Revolution of 1688. I suspect this is for two main reasons: firstly, because there are so many big characters to contend with, not only strong in spirit but also articulate in expressing their faith. It is quite a cast list and includes William Tyndale and Thomas Cranmer, Richard Hooker and Thomas Cartwright, John Donne and George Herbert. There is also a whole chapter dedicated to the Puritan sects – Levellers, Diggers, Ranters and Muggletonians – that sprang up during the Civil War and whose long-term intellectual influences were often as much political as religious, certainly in the case of John Lilburne and the Levellers.

My principal concerns about this book are that, despite its ambitious title and the centrality of religious experience, it is difficult to discern a clear thesis that holds the developments in the narrative together. There is never a sustained consideration of what constitutes the soul of a nation. These concerns are accentuated by the lack of a formal introduction and conclusion. The book starts with a very brief author’s note before plunging directly into the world of Bede. It ends rather abruptly with an examination of the religious thought of the contemporary theologian Dan Cubitt and the suggestion that, in coming full circle back to the 14th Century mysticism of Richard Rolle, Cubitt provides some evidence of the constancy of the English soul.

Peter Ackroyd (Photo by Antony Medley, courtesy of Creative Commons)

This is not a book for everyone, but anyone interested in the development of Christianity in England – and in the historical journey from which the Church of England emerged – will find much to engage with and reflect upon. Ackroyd has certainly provided an excellent ecclesiastical and theological tour d’horizon, full of well-drawn pen pictures of important divines, both conformist and non-conformist. For those in search of a wider examination of the English soul and, in particular, of the nature of the genius that it was inextricably entwined with, I would recommend a follow-up visit to the wider subject of Ackroyd’s Albion, The Origins of the English Imagination. It is one of his best books and deserves to be better known.

The English Soul, The Faith of a Nation by Peter Ackroyd is our now in hardback, published by Reaktion Books. For more information, please visit www.reaktionbooks.co.uk.

Header photo by Dan Smedley, courtesy of Unsplash