With all Tate galleries currently closed, Alex Larman caught the new exhibition on Art Nouveau’s most salacious illustrator just in time. And while we may not be able to visit, there’s an opportunity to view the exhibition room by room – and a terrific curator’s tour – on the Tate’s website…

Somehow, it has been over half a century since the last major exhibition featuring Aubrey Beardsley’s drawings and artwork took place at the V & A, and nearly a century since the Tate last staged a show solely devoted to Beardsley. The new 2020 exhibition seeks to rectify this, even as it promises – be still my prurient heart – ‘deliberately provocative imagery, including nudity and sexually explicit content’. If this is not as bad as the intrusive trigger warnings on the recent Blake exhibition, one still wonders who would be visiting a Beardsley exhibition and expecting the drawings to be anodyne and sexless.

Beardsley occupies a fascinating and ambiguous position in the fin-de-siècle movement. Although he associated with the demi-monde and the homosexuals of the day (or ‘Uranians’, in contemporary parlance), he was either asexual or engaged in an incestuous relationship with his sister Mabel.

He was first taken up by Edward Burne-Jones in 1891, at the age of 18, who told the young man that he usually advised against an artistic career but in Beardsley’s case believed that it was the only viable option available to him. He undertook commission after commission with frenzied speed; he was diagnosed with tuberculosis at the age of seven, died at 25, and managed to complete more than a thousand drawings in just five years.

He was first taken up by Edward Burne-Jones in 1891, at the age of 18, who told the young man that he usually advised against an artistic career but in Beardsley’s case believed that it was the only viable option available to him. He undertook commission after commission with frenzied speed; he was diagnosed with tuberculosis at the age of seven, died at 25, and managed to complete more than a thousand drawings in just five years.

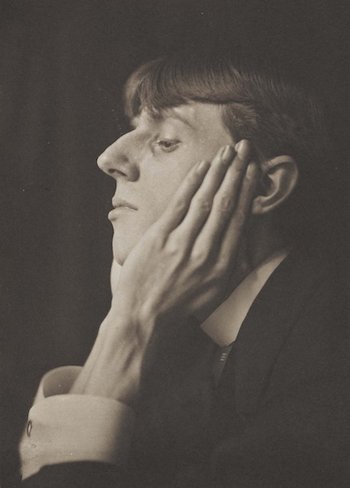

The few photographic portraits that survive of Beardsley show a fey, supercilious fop, but his lively and bawdy sense of humour, shown to full advantage in this new exhibition, made him one of the most sought-after illustrators of the 1890s. His first major commission – it now seems an odd match – was to illustrate Malory’s Morte d’Arthur – which bored him (he introduced irrelevant figures, such as Pan, and phallic symbolism) but gave him the financial means to remain independent. Thereafter, he befriended Wilde’s friend and occasional lover Robbie Ross, and illustrated Wilde’s play Salomé, working from an appalling, near-illiterate translation into French by ‘Bosie’ Douglas.

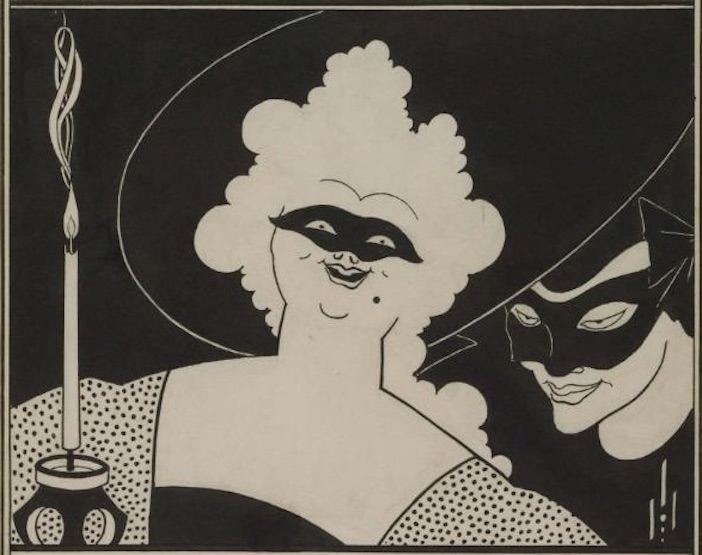

The work made him famous and notorious when it was published in February 1894, and led to his being commissioned to design and contribute to arguably his most famous work, The Yellow Book, a collection of the major artists and writers of the day. Then, in April 1895, Wilde was charged with gross indecency, and Beardsley found himself caught up in the furore. Although he was probably not a practicing sodomite – as the parlance of the day might have it, he neither dined with panthers nor anyone else – this did not matter, and his last years were spent seeking increasingly desperate treatments for his lung haemorrhages in France and Brussels, and producing hugely accomplished work.

Cover Design for ‘The Yellow Book’ Vol.I 1894

The Tate’s exhibition, co-curated by the Beardsley collector and expert Stephen Calloway (who seems to have lent a disproportionate amount of the art and works on display) shows the gallery at its best and worst simultaneously. It is comprehensive, intelligently laid-out and makes some worthwhile points and assumptions about Beardsley’s legacy, but it also spends a great deal of time apologising for the less salubrious aspects of the art, including a number of representations of persons of restricted growth, and there is a bit of silliness when it contrasts ‘what present-day society refers to as LGBTQIA+ identities’ and how Beardsley, who it allows ‘was attracted to women’, ‘was a pioneer in representing what we might now call queer desires and identities.’ Beardsley himself was certainly queer, but in the old-fashioned sense of the word: an odder figure has seldom emerged in British art.

For a young man whose style might seem arch and easily imitable (as can be deduced by some pitch-perfect pastiches in the final room of the display, which explores Beardsley’s afterlife and shifts in reputation), he was remarkably versatile, moving from fairly straightforward representations of Wagnerian scenes to some strikingly bold and erotic artwork, especially his illustrations to Lysistrata, which are full of phalluses, masturbation and what-have-you.

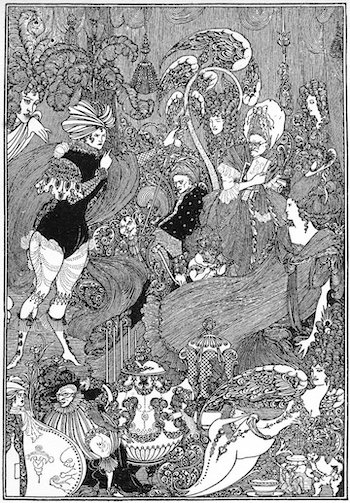

The Cave of Spleen (1896). Scene from the poem, The Rape of the Lock by Alexander Pope.

On his deathbed, he wrote to his publisher Leonard Smithers and asked him to destroy all copies of it and ‘all obscene drawings’; Smithers’ failure to do so is to our benefit. We can only imagine what would have happened if he had been let loose on the collected poems of John Wilmot, earl of Rochester; his illustrations to Pope’s Rape of the Lock, wittily combining decorum and subversion, are the only real indication of what he might have done.

There are several nice revelations. Far from his being an unquestioning disciple of Wilde, Beardsley had an uneasy relationship with the older man even before his downfall and disgrace damaged his career, including unflattering satirical sketches of him in several of his drawings to Salomé. Everyone knows The Yellow Book, but the exhibition persuasively suggests that its 1896 spiritual successor The Savoy, which only lasted eight issues, was as interesting an endeavour, albeit one doomed by its spiritual forbear’s notoriety. And there are tantalising hints of what might have been if he’d lived longer, not least a few sketches for Ben Jonson’s Volpone.

Still, we must be grateful for what we have. If Beardsley is never going to be regarded in the front rank of British artists, he is certainly one of the most distinctive and interesting illustrators that the country ever produced, and his sly, wry and often filthy sense of humour is exhibited here to compellingly licentious effect, making this fascinating, if sometimes too self-aware, exhibition a more than enjoyable alternative to far worthier shows, which, to be frank, could do with more exposed phalluses and masturbating aristocrats.

Aubrey Beardsley at the Tate was to run until 25th May 2020. It may be optimistic thinking, but let’s hope it extends for a period after the ‘lockdown’ and we can experience it. For now, view the exhibition and curator’s tour online at www.tate.org.uk.