With Tate Modern’s universally-acclaimed retrospective on Bonnard entering its closing weeks, Alice Payne tells the story of the show, the artist and his work, and why you should make it a priority not to miss it…

Father of modernism; master of colour;painter of happiness. Numerous titles have been bestowed on Pierre Bonnard, yet his legacy remains among the more divisive of the 20thCentury’s French modern artists. Although his work was highly acclaimed, Picasso was unimpressed, sweepingly dismissing it as a “potpourri of indecision”, while Matisse believed he was “one of the greatest painters”. Today, critics are still divided.

The Tate Modern’s exhibition Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory gathers 100 paintings from around the world to provide a ‘slow look’ at this enigmatic artist, focusing on the last four decades of his career when his inimitable relationship with colour reached its greatest heights. Known for his bucolic, saturated landscapes and intimate portrayals of domestic life with his partner, Marthe de Méligny, Bonnard’s bright paintings and familiar subjects have sometimes obscured the ‘full depth of his expression’ – as Matisse termed it. The Tate’s retrospective seeks to bring these layers to the surface.

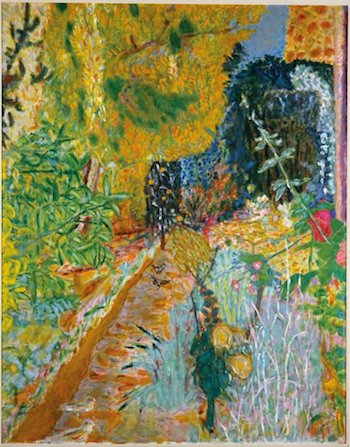

Pierre Bonnard ‘Le Jardin’ (1936)

Ranging from 1912 to 1947, at times this chronological ‘slow look’ can feel a little too slow and could have benefitted from some trimming. But it also unveils formative themes in Bonnard’s life and work, and provides plenty to enchant in his colourful reimagining of the world.

The alchemy with which Bonnard paired pigments and steeped his canvases in colour creates scenes that teeter on abstraction, often with a dream-like quality. “Certainly colour had carried me away. I sacrificed form to it almost unconsciously,” he once confessed. But while a flatness in his drawing is visible in places, to fixate on form undermines the pleasure of his art’s transcended reality, and its emotion.

In Lane at Vernonnet, for example, a small child makes her way down a country track of vibrant corn yellow and lilac beside a house of the same hues – a touching scene of sunny innocence. Yet, while trees of emerald green billow towards an indigo sky, dark shadows lour beneath them to create an unsettling effect. The Garden, meanwhile, is a sultry and inviting tropical scene where apricot foliage separates ink-blue trees, and cerulean plants glow beside a bronze-hued path. Its heady atmosphere exudes allure. Elsewhere, Dining Room in the Country –one of Bonnard’s most remarkable works – captures a pastoral scene with his typical interplay of interior and exterior spaces. Imaginatively cropped, a light-filled dining room opens to an elysian garden view. But the picture feels interrupted by a woman leaning on the windowsill, her glance askance, her presence adding mystique.

Pierre Bonnard ‘Nude in the Bath’ (1925)

Bonnard’s most intriguing paintings are those charting his 47-year relationship with de Méligny – herself often more presence than form. The intimacy with which he documented their lives is heightened by the reverence he gave to fleeting, inconsequential moments. He frequently depicted de Méligny in her daily bathing ritual which she adopted to cure unspecified ailments. Inspired by photography, Bonnard began to crop his compositions in experimental ways and incorporate more natural poses. Whether bathing, drying or dressing – de Méligny appears in radiant hues and relaxed, fluid motions.

Yet as time passes, we see her presence change. Melancholy creeps in, the vibrancy fades, Bonnard’s cropping becomes more extreme and, eventually, she appears entombed in her bath – almost corpse-like in Nude in the Bath. Bonnard painted from memory, building around emotion, which perhaps sheds light on this transition. He once explained: “My painting is finished when I rejoin the emotion that sparked it.”

This emotional reunion could take years, with Young Women in the Garden being the most extreme example. In 1925, Renée Monchaty, Bonnard’s model and mistress, committed suicide a month after his marriage to de Méligny. It took two decades for him to revisit this painting of her. The finished work – where she glows, golden and peaceful – was completed only after de Méligny’s death from a heart attack in 1942.

If Bonnard’s portraits are an honest depiction of his life, his landscapes feel like an escape. He lived in France through two world wars, yet there’s little trace of this here except A Village in Ruins near Ham, painted in 1917 after he visited the Western Front. In it, a figure sits huddled in the foreground, humanised against the metallic uniform of soldiers nearby. The loose brushwork creates a surreal, watery effect, while scorched red hues give the painting an apocalyptic feel. It hangs between two of Bonnard’s most serene landscapes, also painted that year – Donkey in the Garden and Summer. He worked on Summer immediately after visiting the war zone, and the lush, protective landscape, where figures and animals blend into nature, suggests a longing for peace.

Pierre Bonnard, ‘Summer’ (1917)

The Tate’s detailed retrospective works hard to shed light on an elusive artist and enrich the context of his work, yet some enigmas remain. On being called ‘a painter of happiness’, Bonnard famously answered, “he who sings is not always happy”. Footage from 1946 shows him taking a boat trip with friends – his body language reserved, his walk constrained, his clothing wrapped tightly around his frame. The few self-portraits on display are also telling – tense, anguished, and, in the case of The Boxer, engaging in a solitary battle.

Revisiting the question of his legacy, perhaps the proof is in the pudding. Beside the exit, a crowd lingering around the exhibition’s frontispiece – the gloriously bright Studio with Mimosa– seem hesitant to leave. Painted through the duration of the Second World War, it is undoubtedly one of his most beautiful pieces.

Although ‘painter of happiness’ is too trite for an artist whose repertoire extends beyond this, his work exudes a powerful effect. Reluctantly, I step out into a grey and rainy day that feels leached of colour after his vibrant lens.

The CC Land exhibition ‘Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory’ is showing at the Tate Modern until 6th May 2019. For more information and tickets, visit www.tate.org.uk.