“I decided to hang the exhibition mainly on chairs…” she says, before adding, “much in the same way I hang sculptures on chairs.” That’s the artist’s introduction to ‘Sarah Lucas: Happy Gas’, a survey of the 35-year career of the English artist’s work at Tate Britain, London.

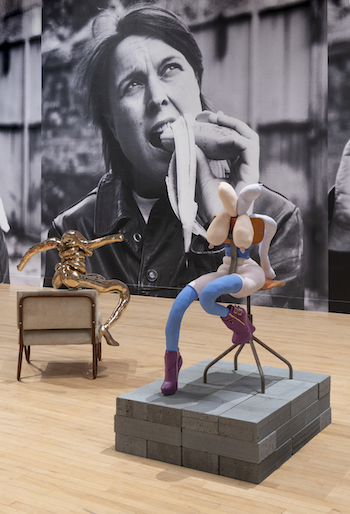

Her words barely explain a show of cocky, irreverent works that challenge gender-stereotyping with sometimes subtle, at times exaggerated innuendo. And she’s right, with over 75 pieces on display, there are a lot of chairs in this show – and all are used to effect. Lucas says that chairs add mood and meaning to her sculptures; they are integral as props to seat her instantly recognisable, uninhibited headless figures, dating from 1997 to 2023.

HAPPY GAS, a reference to nitrous oxide (about to be made illegal to buy in Britain) and a nod to anti-social behaviour, is exhibited in four large galleries, which gives space to large-scale works. The exhibition is narrated by Lucas, a record of her artistic practice in her own words, with anecdotes and stories to describe her work and life, all with a feminist edge. Lucas mixes photography, collage and sculpture that may look like an improvised approach but each piece is carefully manipulated to explore perceptions of sex, or smoking, or food – once seen, who could forget Lucas’s Two Fried Eggs and a Kebab (1999) – intended to create a shock reaction.

HAPPY GAS, a reference to nitrous oxide (about to be made illegal to buy in Britain) and a nod to anti-social behaviour, is exhibited in four large galleries, which gives space to large-scale works. The exhibition is narrated by Lucas, a record of her artistic practice in her own words, with anecdotes and stories to describe her work and life, all with a feminist edge. Lucas mixes photography, collage and sculpture that may look like an improvised approach but each piece is carefully manipulated to explore perceptions of sex, or smoking, or food – once seen, who could forget Lucas’s Two Fried Eggs and a Kebab (1999) – intended to create a shock reaction.

Lucas’s art was first exhibited at Freeze, a now-legendary art exhibition in London, created by artist Damien Hirst in 1988. The show saw the emergence of a group, including Lucas and Hirst, that would be nicknamed ‘YBAs’, or Young British Artists. Many had graduated from Goldsmiths College in London, where Lucas was a student from 1984-87, and the ‘Sensation’ exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1997 firmly established the YBAs as a new presence in contemporary British art.

Portraiture and self-portraiture are integral to Lucas’s work. Her earliest and most well-known portrait is Eating a Banana (1990), a photograph of her younger self, gorging on a banana. It is plastered like wallpaper on the gallery walls. Here was someone questioning, arguing, kicking against established norms in the 1990s. It is a great introduction to her work, both as artist and social commentator, and her message was as relevant in the 1990s as it is today with the #MeToo social movement. A much later photograph Red Sky Dah, from 2018, shows an older Lucas in reflective mood. It, too, is used as large-scale wallpaper, in the final room.

The Tate show surveys her working life through installations, art and sculpture, and is the result of two ideas at work. The first was a story or picture, with each of the four rooms depicting a period of time. The second was to reveal her art practice, through the use of the aforementioned chairs. Both explore her mindset. The earliest work in the show, and the first to be seen, is The Old Couple, 1992. Lucas created it with two wooden chairs. On the seat of one is a penis made of yellow wax, and on the other, a set of false teeth. The chairs stand in for the absent ageing bodies. The work invokes a reaction, whether distaste, poignancy or laughter.

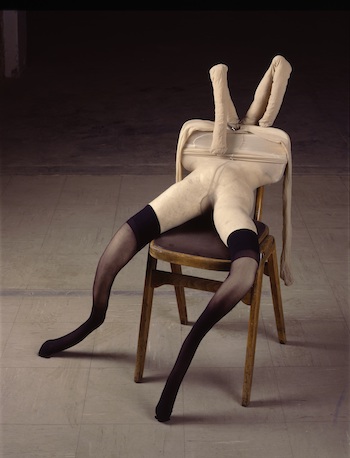

Sarah Lucas, Bunny (1997). Private collection (c) Sarah Lucas

On one wall it is impossible to ignore Fat, Forty and Flab-ulous (1990), a poke at past objectification of women by sex, weight and looks in tabloid newspapers. On another wall is the vast photograph, Chicken Knickers (1997), of Lucas’s lower body wearing white knickers with a dead, plucked chicken attached. Its empty genital cavity is strategically placed. Lucas often uses food to symbolise human genitalia. Close by is Bunny (1997), a headless female figure, lying back on a chair with legs splayed wide, that questions the body as sex object.

Bunny led to the creation of further variations, like Cross Doris (2019), and sixteen new sculptures on the ‘Bunny’ theme premiere in this show, including Cool Chick Baby. The row of bunny-type naked headless torsos, some with their limbs stuffed into bulging tights and spaghetti-style arms that fold over and around distorted, multiple breasts, aim to question the male gaze and the female body. The figures are unreal but channel the essence of sexuality. The textiles used, and the making of them, are associated with women as workers and creators. Lucas’s small black cat – there are three dotted around the exhibition, Tit Tom I/II/III (2023) – are possibly a subtle reference to Edouard Manet’s 1863 painting, Olympia, of a naked courtesan lying on her bed, staring out, returning the male gaze. Olympia’s black cat with hair on end, stares too, and links here to Tit Tom and the ‘Bunny’ sculptures.

Sarah Lucas, This Jaguar’s Going to Heaven, 2018 (Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery)

Lucas’s commentary on sex, death, smoking and perversion, uses different objects as symbols, including lightbulbs, bananas, tabloid newspapers and concrete fish. A burnt-out car – This Jaguar’s Going to Heaven (2018) – with seats made from cigarettes can be seen as a symbol of death. Concrete – a material often associated with masculinity – is used by Lucas as art material in two forms, the raw breeze-block plinths to support sculptures, and in sculptures like a giant marrow, and vast concrete sandwich.

“What I look for in materials,” Lucas explains, “is readiness. Something I can get on with in a spontaneous way …”. To continue, or instigate her conversation, two giant marrows, made of concrete are placed on the front lawn of Tate Britain. They are there to be climbed on and sat upon as an extension of the show outside the gallery. And why the title ‘Happy Gas’? It’s simply because Lucas “fancied a two-word title”, although she adds that she sees it as “uplifting and a bit sinister, too”.

Words that express exactly the content of her remarkable show.

‘Sarah Lucas: Happy Gas’ runs at Tate Britain until 14 January 2024. For more information, and for tickets, please visit www.tate.org.uk.

Photos by Lucy Green