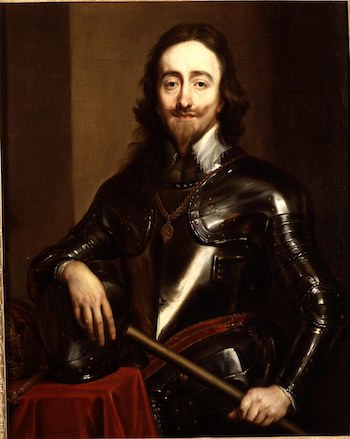

With his latest novel, Act of Oblivion, Robert Harris has entered the turbulent world of England in the mid-17th Century. The setting is the immediate aftermath of the English Civil War and the deep political and religious divisions that were continuing to divide English society. With his unerring eye for a good story Harris has woven a fascinating tale out of the manhunt for two of the regicides involved in the execution of King Charles I. It is a manhunt that crosses the Atlantic to the settlements that had already sprung up in New England and, as with many of his books, Harris has embedded his story deep in the actual historical background. Indeed, in Act of Oblivion only one of his principal protagonists, Richard Nayler, the obsessive leader of the manhunt, is a figure conjured from his imagination.

The title of the book comes from the Act of Indemnity and Oblivion passed by Parliament and signed into law by King Charles II in 1660 as part of the settlement that saw the restoration of the monarchy. The Act guaranteed there would be no reprisals against those who had supported the Parliamentary cause and the Interregnum under Cromwell that followed the execution of King Charles I. The only exceptions to what was, in effect, a general amnesty, were those involved in the execution. Ninety-one names were on the list of those to be held to account of whom twenty-six were no longer alive. Three of them – John Bradshaw (President of the Commission that had tried the King), Oliver Cromwell, and Henry Ireton – were disinterred and posthumously executed. However, it was the thirty-nine surviving members of the fifty-nine commissioners, who had not only sat in judgement over his father but had also gone on to sign his death warrant, whom Charles II most wanted to capture and exact revenge upon.

The title of the book comes from the Act of Indemnity and Oblivion passed by Parliament and signed into law by King Charles II in 1660 as part of the settlement that saw the restoration of the monarchy. The Act guaranteed there would be no reprisals against those who had supported the Parliamentary cause and the Interregnum under Cromwell that followed the execution of King Charles I. The only exceptions to what was, in effect, a general amnesty, were those involved in the execution. Ninety-one names were on the list of those to be held to account of whom twenty-six were no longer alive. Three of them – John Bradshaw (President of the Commission that had tried the King), Oliver Cromwell, and Henry Ireton – were disinterred and posthumously executed. However, it was the thirty-nine surviving members of the fifty-nine commissioners, who had not only sat in judgement over his father but had also gone on to sign his death warrant, whom Charles II most wanted to capture and exact revenge upon.

The manhunt that followed resulted in the capture of twenty-four of them. Nine were hung, drawn and quartered, three died before they could be executed and twelve were imprisoned. It is two of this thirty-nine, Edward Whalley and his son-in-law William Goffe, who are Harris’s principal protagonists and the quarry of the manhunt that is at the heart of Act of Oblivion. However, this is no action-packed manhunt in the style of a True Grit or a Bonnie and Clyde. It is much more of a slow burn. This is not least because the hunt for Whalley and Goffe takes place across two decades but also because it becomes intertwined with the politics of the developing American colonies. It is here that the two regicides find shelter amongst sympathetic puritans who formed most of the population of the scattered settlements that made up New England in the 1660s.

Central to Harris’s story is the invented character of Richard Nayler, the regicide hunter-in-chief. Relentless in the pursuit of his prey and driven by a deep-seated religious fervour to avenge the death of his King, he always carries a handkerchief stained with the blood of Charles that had dripped through the gaps in the planks of the execution platform. Nayler is not hunting just Whalley and Goffe in New England. He is also on the trail of other regicides in England and on the mainland of Europe in cities as diverse as Amsterdam, Paris and Geneva as information about their whereabouts becomes available.

With Nayler, Harris has created a character who mirrors the fanaticism that always seems to consume some on both sides when societies are divided, whether over political ideology, religion, or cultural and social norms. Nayler’s fanaticism is reflected back in the dogmatism of the equally immoderate William Goffe. It is only Goffe’s father-in-law Edward Whalley who occasionally questions the certainty of his political and religious convictions. But Nayler is of use to Harris not just as a central character but also as a means of exploring the wider historical events taking place in the American colonies – the settlers’ relationships with the local Indian inhabitants, for instance, and the English acquisition of New York from the Dutch.

With Nayler, Harris has created a character who mirrors the fanaticism that always seems to consume some on both sides when societies are divided, whether over political ideology, religion, or cultural and social norms. Nayler’s fanaticism is reflected back in the dogmatism of the equally immoderate William Goffe. It is only Goffe’s father-in-law Edward Whalley who occasionally questions the certainty of his political and religious convictions. But Nayler is of use to Harris not just as a central character but also as a means of exploring the wider historical events taking place in the American colonies – the settlers’ relationships with the local Indian inhabitants, for instance, and the English acquisition of New York from the Dutch.

Harris’s forte is in capturing not only the essence of the political and religious divisions of the time but also the way religious belief played such an important part in daily life as well as in politics. One of first characters to appear in the book, one Daniel Gookin, who lives in Cambridge Massachusetts, and with whom Whalley and Goffe first take refuge, describes the atmosphere of New England in one pithy sentence: “Boston is full of rogues and royalists, whereas here they will be among the godly.” The godly referred to the predominantly puritan population of New England, many of whom had crossed the Atlantic to escape persecution and enjoy what they hoped was political and religious freedom in a new land. For some, the most radical, whether in politics such as the Levellers or in religion such as the Fifth Monarchy Men, persecution had continued even during the Cromwellian Protectorate.

Some of the protagonists in Harris’s earlier historical novels are more appealing than those you’ll find here. But the world in which Whalley, Goffe and Nayler live is far less tolerant and forgiving than the one in which we like to think we live. A slow burn, maybe, but this is a story that is not without tension, excitement, and the confronting of moral dilemmas. Whalley and Goffe have to live an ocean apart from their families and with the knowledge that capture would result in a terrible death. Last but not least, Act of Oblivion also hints at the developing independence of character of the American colonies that gradually grew into the mindset that lay behind the struggle for independence that would come a century later.

Act of Oblivion is out now in hardback, audiobook download and ebook, published by Hutchinson Heinemann.