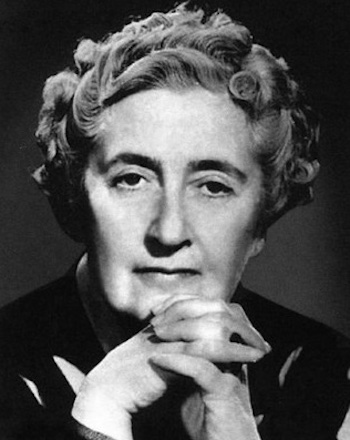

Like, I suspect, most people, my knowledge of Agatha Christie has been limited to having watched the long-running Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple series on television. As to the author herself, I knew little of the circumstances and experiences of the life which produced such popular and deviously plotted detective stories. If I had a picture in my mind of the author it was of an elderly lady, Miss Marple-like, pen in hand, bent over her desk with a glass of sweet sherry close at hand, writing murder stories usually set in the small world of a country village.

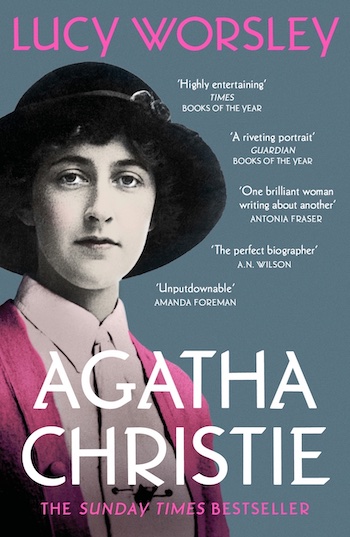

Reading Lucy Worsley’s evocative recent biography has replaced this idle caricature with the interesting, sharp-minded, adventurous woman whose horizons extended far beyond that of any village. That said, the persona Christie presented to the public was essentially a mask. For all her success and the fame it brought, she remained an essentially shy and modest person. When a party was held to celebrate the 2,239th performance of her play ‘The Mousetrap’, Christie, the guest of honour, was not recognised by the staff at the venue and turned back. Instead of telling them she was the principal guest she just quietly slipped away. For Worsley, as the sub-title of her book and the title of her preface indicate, Christie was ‘A Very Elusive Woman’ who was ‘hiding in plain sight’.

Reading Lucy Worsley’s evocative recent biography has replaced this idle caricature with the interesting, sharp-minded, adventurous woman whose horizons extended far beyond that of any village. That said, the persona Christie presented to the public was essentially a mask. For all her success and the fame it brought, she remained an essentially shy and modest person. When a party was held to celebrate the 2,239th performance of her play ‘The Mousetrap’, Christie, the guest of honour, was not recognised by the staff at the venue and turned back. Instead of telling them she was the principal guest she just quietly slipped away. For Worsley, as the sub-title of her book and the title of her preface indicate, Christie was ‘A Very Elusive Woman’ who was ‘hiding in plain sight’.

Worsley is clearly an evangelist for Christie. Her enthusiasm (Worsley is an enthusiast in all that she does) and her admiration for her protagonist are evident throughout the book as is her belief that Christie is too easily underrated. Only very occasionally does her evangelism get in the way of her otherwise measured judgments. The principal occasion is when discussing the literary merits or otherwise of Christie’s writing style and where she might sit in the cultural hierarchy. Her suggestion that she might sit under the same umbrella as the modernists of the 1920s and 1930s such as Auden, Joyce and Lawrence is, for all Christie’s skills as a writer of clever, adroitly written murder mysteries, surely a step too far. Where Worsley is on far stronger ground is in pointing out that Christie was very interested in the modern world as it kept changing around her. She frequently used current events for her plots, was thrilled surfing in Hawaii, loved owning and driving fast cars, enjoyed reading science fiction and was an adventurous traveller especially in Iraq in support of her second husband, Max Mallowan, and his archaeological expeditions. Christie may not have been a literary modernist, but she was no wallflower.

She was born in 1890 into a prosperous family who lived in Torquay. By the time Christie was 18 she was an eligible young woman who was already being pursued, whether in the fashionable Gezirah Palace Hotel, Cairo where she and her widowed mother spent three months, or back in England swept up in a social whirl of country house parties, dances and amateur theatrics. By October 1912, when she met the handsome and dashing Archie Christie, an officer in the Royal Artillery, later in the Royal Flying Corps, she had already been proposed to nine times and been engaged once. They got married on Christmas Eve 1914 when he returned briefly from the Western Front.

The outbreak of the First World War changed everything. The social whirl was replaced by voluntary work in an auxiliary hospital established in Torquay town hall. It was a brutal introduction for a lady of leisure both to work, initially as little more than a cleaner, and to the horror of war. After two years she moved from being on the wards to paid work in the hospital pharmacy. It was here she started to acquire the medical knowledge that underpinned her use of poisons, sometimes unusual ones but most frequently cyanide, as her favourite method for the murders in her novels.

First edition of The Mysterious Affair at Styles

It was also at the hospital, as a wife alone at home with her husband away at the war, that she started to write in her spare time. Her first book, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, partly the result of a bet with her sister that she could not write a detective story, was first drafted in 1916-17 and eventually published in 1920 after six rejections. It laid the foundations of so much that was to follow with the introduction of both Hercule Poirot and Captain Hastings, the concept of the finale with the great reveal and the trick of the ‘hidden couple’ where apparently very different people have a masked connection.

The most dramatic moment in Christie’s life was her famous eleven-day disappearance in December 1926. It rapidly became a cause celebre not least because by then she had established herself as a successful writer of detective stories with the publication of a further five novels since the publication of The Mysterious Affair at Styles. Indeed, the summer of 1926 had seen the publication of what was one of her most acclaimed books – The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. Her disappearance sparked increasingly dramatic speculation fuelled by the competition between the police trying to find her and by the press, not least the Daily Mail. Even today there continues to be speculation as to why she disappeared. Worsley handles this sad saga and the speculation that still surrounds it with commendable good sense and believes, on balance, that it was some kind of breakdown without any ulterior motives. The reader can make up their own mind.

Amongst the many strengths of Worsley’s biography are not just the engaging narrative but also the well-judged and illuminating description of the changing England into which Christie was born and in which she made her way. She is also adept and showing how Christie adapted to the changes in world around her, especially, but not only, the social and psychological impacts of the First World War. These are reflected in the strong, clever women, often alone, that feature in her stories such Ariadne Oliver, a writer of detective stories, who appears in at least seven novels usually with Poirot such as Dead Man’s Folly and Elephants Can Remember. As for a younger generation there is the adventurous Anne Bedingfield in The Man in the Brown Suit and the shrewd and equally adventurous Lucy Eyelesbarrow in the 4.50 from Paddington. There is, of course, her other principal detective, the inimitable Miss Marple who appears in twelve novels.

The faded elegance and financial insecurity of some of the country house settings of many of her stories reflects both the impact of the war and the economic challenges of the 1920s and 1930s. That said, the settings of her stories were not stuck in a time warp. She would frequently get ideas for characters and story lines from current events as in the case of the racing driver in her 1965 Miss Marple novel Bertram’s Hotel. He was modelled on Roy James, the getaway driver in the Great Train Robbery.

Christie emerges from Worsley’s book not just as a better writer than she is often given credit for but also more than just the creator of complex, clever plots full of misdirection, false assumptions and stereotypical descriptions of characters designed to mislead. Christie may not be a literary giant, she never set out to be. Once, when asked how she would like to be remembered she is reputed to have replied ‘as a respectable writer of detective stories ‘. In practice her writing has a clarity and conciseness that has more depth than first appears. There may not be deep psychological analysis but there are certainly well delineated characters whose different types relate to people one may have met. Living as she did through the England of the First and Second World Wars and of the decline of Empire it is hardly surprising when the behaviour and views of her characters are occasionally uncomfortable for modern sensitivities.

Christie emerges from Worsley’s book not just as a better writer than she is often given credit for but also more than just the creator of complex, clever plots full of misdirection, false assumptions and stereotypical descriptions of characters designed to mislead. Christie may not be a literary giant, she never set out to be. Once, when asked how she would like to be remembered she is reputed to have replied ‘as a respectable writer of detective stories ‘. In practice her writing has a clarity and conciseness that has more depth than first appears. There may not be deep psychological analysis but there are certainly well delineated characters whose different types relate to people one may have met. Living as she did through the England of the First and Second World Wars and of the decline of Empire it is hardly surprising when the behaviour and views of her characters are occasionally uncomfortable for modern sensitivities.

Worsley’s biography of Christie is an excellent read whether for the already dedicated Christie fan or for the newcomer. Not that Christie needs Worsley’s help. Not only was her output prodigious – she wrote 66 crime novels, 6 non-crime novels (published under the pseudonym Mary Westmacott) and 150 short stories, not forgetting the 10 of the 20 plays she wrote that were also published – but her publishing success was and continues to be remarkable. She is only outdone by the Bible and Shakespeare. She is the most translated writer of fiction of all time, and around 2 million copies of her books are still sold in English most years. People may no longer talk about ‘a Christie for Christmas’ but her undoubted gift for detective fiction clearly still captures the imagination of many today.

Agatha Christie, An Elusive Woman by Lucy Worsley is out now in paperback, published by Hodder and Stoughton. For more information, please visit www.hodder.co.uk.

Header image courtesy of BBC Picture Library