This wonderfully researched and beautifully written book tells the extraordinary story of Charles Masson. Full of colour, adventure and larger than life characters it makes the fictional Indiana Jones seem dull by comparison. The story begins in 1827 when James Lewis, a working-class Londoner, deserted from the army of the East India Company, escaped to the wilds of Afghanistan and somehow survived.

In the life that followed he was in turn beggar, storyteller, doctor and traveller before re-inventing himself as Charles Masson ‘an American gentleman from Kentucky’ and becoming confidant and adviser to rulers, archaeologist, antiquarian, survivor of assassination attempts, spy, prisoner and finally an ill and lonely failure. It was in Kabul that he discovered his life’s two principal passions: a deep interest in the ancient history of Afghanistan and an obsession with the life of Alexander the Great.

In the life that followed he was in turn beggar, storyteller, doctor and traveller before re-inventing himself as Charles Masson ‘an American gentleman from Kentucky’ and becoming confidant and adviser to rulers, archaeologist, antiquarian, survivor of assassination attempts, spy, prisoner and finally an ill and lonely failure. It was in Kabul that he discovered his life’s two principal passions: a deep interest in the ancient history of Afghanistan and an obsession with the life of Alexander the Great.

These two passions saw this self-educated survivor become the first European to study the rich archaeological history of Afghanistan with his findings being discussed in learned societies from London to Bombay. He brought to light the rich Hellenistic-Buddhist culture that had flourished in the aftermath of Alexander the Great, discovered the lost city of Alexandria near Bagram and the ancient Harappa civilisation of the Indus and, by analysing the inscriptions on his collection of coins, deciphered the ancient Kharosthi script. His single most dramatic find was the golden casket of Bimaran, half Hellenist and half Buddhist, that is now in the British Museum.

In Edmund Richardson, Masson has found the perfect biographer. This book will surely see Masson emerge from the shadows where he has been languishing and receive the recognition he rightfully deserves. Not least, because Richardson knows how to tell a great story, and this is a great story. Although, as Richardson points out at the end of his first chapter, many stories about Charles Masson, especially those that Masson tells about himself, may not always be completely true. However, it was certainly no easy life. His return journey from the Buddhas of Bamiyan was horrific. By the time he reached Kabul his clothes were in tatters, his feet blistered and his eyes almost blinded by snowstorms.

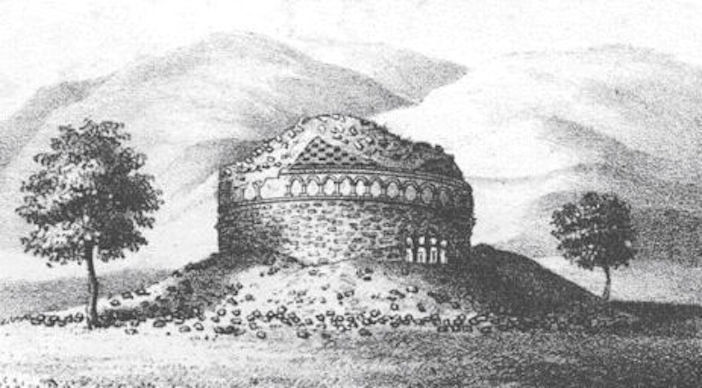

The Stupa No.2 at Bimaran, where the Bimaran reliquary was excavated. Drawing by Charles Masson.

Richardson also brings to life the Victorian penny-dreadful cast of characters that fill the pages of Masson’s story. They include Dost Mohammed the enigmatic ruler of Afghanistan, renowned in the same breath for his commitment to justice, sarcasm and violence; Josiah Harlan, an endlessly conspiratorial American adventurer and one of the models for Kipling’s story ‘The Man Who Would Be King’; Captain Wade, an East India Company spymaster and nemesis of Masson; last but not least, Lieutenant Loveday, an ambitious political officer with a vicious streak who would have fitted in well to Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’. Even those with walk-on parts, such as two French archaeologists, add colour to the story. Climbing behind the Buddhas of Bamiyan in 1924 to explore a cave they were disappointed to discover on its rock walls two lines scratched by Masson in 1832:

‘If any fool this high samootch explore,

know Charles Masson has been here before’.

Masson’s achievements should have marked him out as one of the most important of that eccentric band of Victorian adventurers – explorers, scholars, diplomats, spies, soldiers and occasional charlatans – who traversed the deserts and mountains of Afghanistan and the North-west Frontier provinces of British India, in search of fame and fortune. Sadly, Masson never received the recognition he deserved, largely because he never managed to escape the clutches of the East India Company.

The pardon he was granted for his desertion was kept in abeyance to force him to spy for them. His library, along with his precious notes and priceless collection of finds, was destroyed by a violent mob in Kabul because of his links to the Company. To add insult to injury he then found himself imprisoned by his own employers. Returning to London a broken man he ended his life in poverty near Potter’s Bar. He faded into obscurity making occasional appearances in the footnotes and margins of the histories of the ‘Great Game’ played out in Afghanistan and the North-west Frontier by agents of the British Raj in India.

The pardon he was granted for his desertion was kept in abeyance to force him to spy for them. His library, along with his precious notes and priceless collection of finds, was destroyed by a violent mob in Kabul because of his links to the Company. To add insult to injury he then found himself imprisoned by his own employers. Returning to London a broken man he ended his life in poverty near Potter’s Bar. He faded into obscurity making occasional appearances in the footnotes and margins of the histories of the ‘Great Game’ played out in Afghanistan and the North-west Frontier by agents of the British Raj in India.

Richardson also brings to life the cultural richness and complexities of the world in which Masson was trying to survive. Afghanistan, then as now, was an ethnic, religious and political crossroads; then as now, it was also blighted by violence. Anyone who has followed its tragic recent history will find so many of the place names linked to Masson’s story resonate with current events: Bagram, Bamiyan, Kabul, Kandahar, Herat, Helmand and Peshawar. That Masson survived for so long as an outsider in the challenging environment of Afghanistan was down to his obvious respect for the customs of the people he lived amongst. It was only once he was forced to become a spy for the East India Company that his position and his relationships started to unravel. Richardson has written a superb book. It is by turns an adventure story that fizzes along, a colourful biography and a fascinating voyage of cultural exploration. Above all it is just a joy to read.

Alexandria, The Quest for the Lost City by Edmund Richardson is published by Bloomsbury, priced £22.50. For more information, please visit www.bloomsbury.com.

Header image: ‘Mountains at Zirta Bolan Pass’ (1839) coloured lithograph from a sketch by W L Walton, courtesy of the National Army Museum.