As I started writing this review there was a minor storm in a teacup over the book and the news that the BBC were planning a new series on Colditz based on it. Some were spluttering over their tea at what seemed to be yet another undermining of war heroes, not least Douglas Bader, and others were rejoicing at another nail in the coffin of our imperial history. Neither will be satisfied if they bother to read the book as they will discover that Ben Macintyre is not an iconoclast as his eloquent defence of his approach in The Times made clear.

To roll back the years for a moment, for an older generation the Colditz story was one about jolly good British chaps outwitting heavy handed, humourless and often dim-witted German guards. It was a version of the story largely created by the 1952 book written by Major Pat Reid MBE MC (a Colditz escaper) upon which the 1955 film was based and for which he was the consultant. The 1972-74 BBC TV series also fully bought into the jolly good chaps version. What Ben Macintyre brings to life in his version ‘Colditz, Prisoners of the Castle’ is far more nuanced.

To roll back the years for a moment, for an older generation the Colditz story was one about jolly good British chaps outwitting heavy handed, humourless and often dim-witted German guards. It was a version of the story largely created by the 1952 book written by Major Pat Reid MBE MC (a Colditz escaper) upon which the 1955 film was based and for which he was the consultant. The 1972-74 BBC TV series also fully bought into the jolly good chaps version. What Ben Macintyre brings to life in his version ‘Colditz, Prisoners of the Castle’ is far more nuanced.

In Macintyre’s book, Colditz was more international, mostly not so jolly, not very healthy either physically or mentally, and daily life was, more often than not, just plain boring. That said, Macintyre also makes clear that life at Colditz did contain colour and humour, that it was most certainly full of inventiveness, sometimes extraordinary daring and, on occasion a great deal of courage. Much of this was because the planning of escapes and generally trying to outwit and annoy the German guards was one of the best ways of keeping occupied and amused. It was also the only way the prisoners could feel they were still making some kind of contribution to the war effort.

He also shows the members of the all-male prison community, whether prisoners or guards, with all their prejudices of the time whether social, political or racial. Some turn out to have feet of clay or to be just unpleasant, many fit easily into the 1950s jolly good chaps stereotype, while others, little known till now, turn out to deserve much more recognition for their conduct and achievements. In short, Macintyre illustrates how the manifold strengths and weaknesses of humanity were present in the dour, claustrophobic, Disneyesque castle that was Colditz.

The international make-up of the prisoners at Colditz is well illustrated by the make-up of the successful escapers: of the 32 estimated to have made ‘home runs’ 12 were French, 11 were British, 7 were Dutch, one was a Pole and one a Belgian. The first soldiers to be imprisoned at Colditz were a handful of Poles in November 1939 but by the middle of 1941 the castle held more than 500 prisoners of which the majority were French and Polish. Even the Dutch were more numerous than the British contingent of 50 (this included Canadians, Australians, New Zealanders and South Africans). It was not until the middle of 1943 when the Germans moved almost everyone else to other locations that the British contingent, which had grown to about 230, became the biggest group and remained so for almost all of the rest of the war.

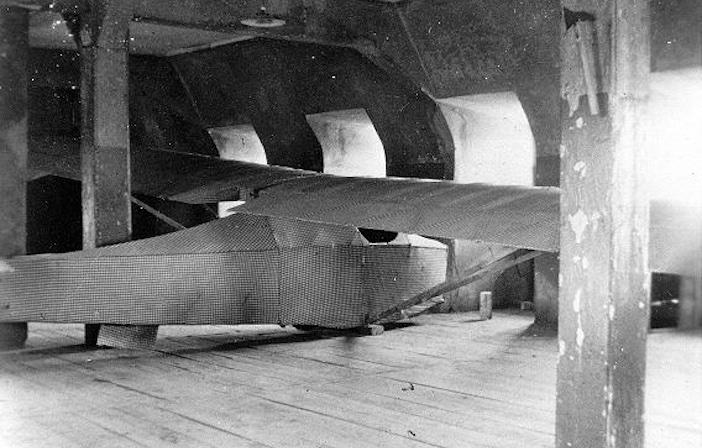

RAF POWs in Colditz, including S/Ldr Douglas Bader (front row, centre) and F/Lt Dominic Bruce (front row, far right), who made 17 escape attempts from camps during WW2

It should come as little surprise that Macintyre’s description of the POW community exposes the extent to which it was infected with social elitism and racism. It was after all another place in another time. There was even a Colditz version of the Bullingdon Club and orderlies provided by the Germans from other rank prisoners for senior officers and the prominente. The latter were prisoners regarded as of particular value by the Germans because of their family connections. It may have been a prisoner of war camp but it was still an upstairs-downstairs world in Colditz.

As for racism it was present in the frequently appalling treatment of Captain Birendranath Mazumdar, a doctor in the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC), who had joined up despite being an opponent of British rule in India and a supporter of Gandhi and Bose. Having sworn allegiance to the British Crown when joining the RAMC Mazumdar refused to break his oath and escape his imprisonment by changing sides despite every inducement offered him by Bose and the Nazis. His honourable behaviour fully deserves the recognition that Macintyre gives him, all the more so given the way he was treated by his fellow prisoners.

The most important German character in the book is Reinhold Eggers, the senior security officer and the longest serving member of the garrison. He was equally fastidious in carrying out his security duties as he was in observing the Geneva Conventions. Much caricatured by the prisoners, not least by Airey Neave, and hated by some for his efficiency as a security officer, this anglophile English teacher turned wartime soldier, who had never been a member of the Nazi party, emerges from Macintyre’s book as a fundamentally decent man.

The most important German character in the book is Reinhold Eggers, the senior security officer and the longest serving member of the garrison. He was equally fastidious in carrying out his security duties as he was in observing the Geneva Conventions. Much caricatured by the prisoners, not least by Airey Neave, and hated by some for his efficiency as a security officer, this anglophile English teacher turned wartime soldier, who had never been a member of the Nazi party, emerges from Macintyre’s book as a fundamentally decent man.

There is a tragic irony to his early post-war fate. Returning to his home and to teaching in what was now communist East Germany, he was sentenced to ten years hard labour by a Soviet military tribunal. Released in 1955 he was expelled to West Germany. The real irony, and certainly injustice is that the NKVD camp to which he was sent was a re-named Nazi concentration camp, Sachsenhausen, where by 1951 he was one of only 1,500 survivors out of over 12,000 inmates. Eggers had exchanged life as the servant of one tyranny for life as the victim of another.

In adding so much more colour to the story Colditz, Macintyre does not forget that at heart this was a prisoner of war camp, many of whose inmates were dedicated to continuing the war by other means, of which escaping was the regarded as the best. The result was a remarkable display of ingenuity that ranged from getting all sorts of items smuggled in via Red Cross parcels to vandalising the castle in search of useable materials; from digging tunnels to creating disguises; from forging documents to bribing guards. The pièce de resistance´, although mercifully unused, was the building of a glider in the roof of the castle.

Continuing the war by other means and the displays of ingenuity accompanying it were not limited to escaping. There were hidden radios constructed to keep up to date with the world outside – here the French were especially effective and one of their radios was not discovered until after the war – and a local intelligence network was built to collect and send intelligence via coded letters. A key figure in the latter was Julius Green, a Jewish army dentist from Scotland. Enthusiastic cryptographers will find that Macintyre has included the code that was used in an appendix.

Macintyre has not undermined the Colditz story of old. If anything, he has enhanced it by adding to its role of honour and to the humanity, good and bad, of those caught up in it. As for Bader his extraordinary courage and skill are not undermined despite the discovery, for those who did not previously know, of what an arrogant and unpleasant man he was when not in the cockpit of a fighter plane. Just as one can admire the music of Wagner the composer while despising his politics so one can admire the courage of Bader the pilot while deploring his appalling arrogance. I just hope that the BBC will manage to preserve the balance and nuance of this well-written, well-researched and enjoyable book.

‘Colditz, Prisoners of the Castle’ by Ben Macintyre is out now, published by Penguin Books.

Photos courtesy of WikiCommons