2020 marks 40 years since the initial publication of John Kennedy Toole’s comic masterpiece A Confederacy of Dunces. Many already know the story of how Toole, depressed by constant rejection, killed himself before the book was published, and how it came to be eventually brought into public view thanks to his mother’s tireless efforts, winning the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. But what virtually nobody has ever pointed out is the debt Toole owes to an obscure British comic novel from the Twenties, Augustus Carp, Esq, by Himself.

Toole’s protagonist, the monstrous and delusional Ignatius J Reilly, is much given to wailing about ‘fortuna’, who he claims has unfairly maligned him, when not moaning about his ‘valve’ or displaying grotesque episodes of flatulence. His predecessor Augustus Carp has a similarly high opinion of himself as a ‘Xtian’ gentleman, and much of the comedy in both books comes about from the gulf between reality and fantasy. Yet Ignatius, for all his awfulness, is a strangely compelling character, and the reader eventually comes to feel a certain sympathy for his quest against the modern world.

Carp, meanwhile, is one of English comic literature’s great horrors, and hilariously, constantly devoid of any sense of how he comes across. He presents himself from the beginning of his saga as a truly pompous, absurd figure, writing ‘It is customary, I have noticed, in publishing an autobiography to preface it with some sort of apology. But there are times, and surely the present is one of them, when to do so is manifestly unnecessary.’ We are introduced to Carp, his put-upon mother and his vile father, the inhabitants of Mon Repos in Camberwell (‘such was his distrust of French morality that he had always insisted, both for himself and others, upon a strictly English pronunciation’).

Carp, meanwhile, is one of English comic literature’s great horrors, and hilariously, constantly devoid of any sense of how he comes across. He presents himself from the beginning of his saga as a truly pompous, absurd figure, writing ‘It is customary, I have noticed, in publishing an autobiography to preface it with some sort of apology. But there are times, and surely the present is one of them, when to do so is manifestly unnecessary.’ We are introduced to Carp, his put-upon mother and his vile father, the inhabitants of Mon Repos in Camberwell (‘such was his distrust of French morality that he had always insisted, both for himself and others, upon a strictly English pronunciation’).

Carp senior is a sidesman of the Church of St James-the-Less and much given to enormous bouts of overeating. The results are predictable. ‘My father experienced an acute reaction, and for many weeks would become a martyr not only to neurasthenic indigestion, but to digestive neurasthenia accompanied by flatulence of the severest order. For months on end, indeed, my mother would be obliged to sit by his bedside in case he should wake up and require abdominal kneading, and few were the nights upon which she had not in addition to go downstairs and make him some cocoa.’ However, he remains undaunted. ‘His breakfast the next morning would be as hearty as usual. And he was never deterred by even the most obstinate inflation from the performance of a moral or religious duty.’

Augustus is not a handsome man. ‘It is true that I have suffered, and still do suffer, apart from the indigestion previously referred to, from several forms of neurasthenia, a marked tendency to eczema, occipital headaches, sour eructations, and flatulent distension of the abdomen.’ There is some good news, however. ‘But from small-pox, although entirely unvaccinated, I have always remained singularly immune.’ He makes his way in the world through a combination of priggishness, intolerance and blackmail, ensuring that his ‘Xtian’ magnificence is recognised by those around him, and if anyone does not, then they are liable to find themselves in a dire situation.

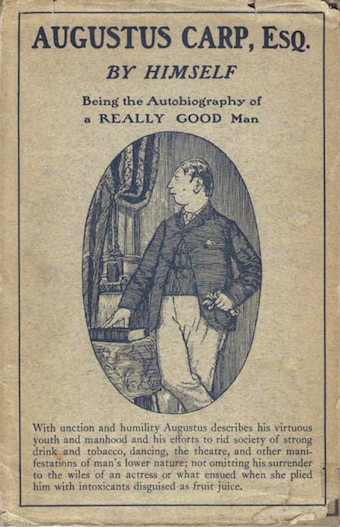

Augustus Carp, first edition cover

Eventually – blessedly – Carp overreaches himself. Just as Ignatius patronised cinemas with particular interest in the ‘obscene’ films, Carp finds himself drawn, along with his hapless sidekick Ezekiel Stool (the names are especially brilliant), to the Empress Theatre and its beauteous star Mary Moonbeam. He intends to take her in hand in a most Xtian fashion – ‘She has so much to learn,’ I said, `so much to understand. She’s like a little child, Ezekiel, just as you supposed – a female child that has never been properly taught’ – but it transpires that Miss Moonbeam has other intentions in mind, revolving around the liberal application of ‘Portugalade’ to Carp, which leads to a drunk scene to rival the great ‘Merrie England’ setpiece of Lucky Jim.

Carp eventually recovers his footing, of sorts, but the book ends with his mother escaping from her long domestic bondage to Paris (‘I’m going to be sick’), Carp reluctantly married to Ezekiel’s repulsive sister Tact (‘I’m giving you a minute in which to decide’) and a redeemed Stool a man-about-town with chambers at the Albany. It is a sublime, constantly surprising comic delight, and yet remains mainly unknown today. It would probably be entirely forgotten were it not for Anthony Burgess, who championed the novel in the Sixties, and also for the eventual revelation of the anonymous author. It transpired that the book was written by Henry Howard Bashford, a distinguished doctor who eventually became Honorary Physician to George VI, and whose other works included the no doubt rib-tickling Vagabonds in Périgord and Doctors in Shirt Sleeves.

Augustus Carp remains his masterpiece. I first read it, appropriately enough, on the train to Windsor, and I can seldom remember having been overcome with such giddy hilarity. Page after page, written in the same knowingly solemn, ostensibly humourless style, contains some of the best comic writing of the twentieth century. At one point, Carp’s father, now the sidesman at St James-the-Least-of-All, has been angered by the gift of what he perceives as a brazen image, and begins his denunciation of those who presented it to the church. His ferocity even staggers his son:

Sir Henry Howarth Bashford (1949) by Walter Stoneman

‘Beginning, as I have said, in a low voice, yet one that was crystal clear in its penetrating capacity, for the first five minutes or so my father refused to allow himself the adventitious aid of a single gesture. It was the gathering of the storm, as it were, the marshalling of the hosts of heaven, composed but relentless, above the brazen image. Then he paused for a moment, indicating the aspidistra that stood upon a tripod in the corner of the room.

`Now, say that’s the bird’ he said, and suddenly, like a flash of lightning, his right index finger was quivering upon the air. Involuntarily I leapt round and stared at the aspidistra, and then like the deafening down-burst of a tornado, my father expanded his chest, threw back his head, and opened the full flood-gates of his passion. Pallid and cowering, I crept behind the armchair, while syllable after syllable rent the night, and the delirious harmonium leapt and crashed down again beneath the palpitant thunder of his blows. Then almost as suddenly he stopped.’

And then, when a visitor appears and politely regrets having missed the spectacle, he does it once again. To read Augustus Carp is to come across the bastard relative of Diary of a Nobody and A Confederacy of Dunces, and like those two comic masterpieces, it is embarrassingly, hilariously entertaining. (Even the chapter headings are brilliant.) I envy anyone reading it for the first time, for they are in for a sublime treat.