For most people Malta is a place where you go on holiday, lie on sandy beaches, take part in water sports or wander through the historic streets of Valetta and Mdina. Few know that between June 1940 and the end of October 1942 the island came under sustained air attack from German and Italian aircraft flying from bases in Tunisia and Sicily. Let alone that in April and May 1942 more bombs fell on Malta than London received during the entire blitz. Even fewer are likely to know that to provide vital supplies to the beleaguered island the Royal Navy launched its biggest naval operation since the Battle of Jutland under the codename Operation Pedestal.

At the heart of the operation was a modest collection of fourteen merchant ships all of which bar one carried mixed loads of food, fuel and ammunition so that when a ship was sunk not all of one element of the resupply would be lost. The fourteenth, and the most important, an American oil tanker, the Ohio, was the one exception. It was filled to the gunwales with 11,000 tons of the fuel and lubricants needed to keep the aircraft defending Malta flying. To shepherd this small but important convoy to Malta the Royal Navy assembled two battleships, seven cruisers, thirty-two destroyers, seven submarines, four corvettes and four of the seven aircraft carriers that it possessed.

It is the violent and dramatic story of Operation Pedestal that Max Hastings, well known as a military historian, tells in this his first foray into war at sea. It is not a disappointment. Hastings displays the same grasp of the key strategic and operational issues of sea warfare he has shown when writing about land warfare. He is also an expert at highlighting the unintended consequences of decisions made under pressure and how battle ruthlessly exposes technological limitations.

It is the violent and dramatic story of Operation Pedestal that Max Hastings, well known as a military historian, tells in this his first foray into war at sea. It is not a disappointment. Hastings displays the same grasp of the key strategic and operational issues of sea warfare he has shown when writing about land warfare. He is also an expert at highlighting the unintended consequences of decisions made under pressure and how battle ruthlessly exposes technological limitations.

For example, the decision by the Admiral in command of the convoy and its escorts to move to a destroyer rather than another cruiser when his flagship HMS Nigeriawas put out of action by an Italian submarine. Command of his warships and control of the convoy immediately become much more difficult as destroyers lacked the range of radio communication equipment enjoyed by a cruiser. As for technology, the decision to equip only a couple of the convoy escorts with the radios needed to communicate with aircraft was brutally exposed when under air attack. Once the radios on these ships were damaged it was no longer possible to communicate directly with the fighters coming to defend the convoy. This was an avoidable error given bitter experience had already shown fighter aircraft provided the only effective defence for ships under air attack.

Hastings is in his element bringing alive the human experience of war at sea whether in a surface ship, a submarine or an aircraft. He interweaves excerpts from the records and memories of the combatants on both sides of the conflict into his narrative and his own experiences from the Falklands War also clearly help him read between the lines. These well-chosen vignettes include the frequently ignored courage of the stokers and engineers working in the bowels of their ships with little chance of escape from death and injury.

When it came, whether from torpedo or bomb attack, escape from the resulting blast, fires, boiling hot steam and in-rushing sea depended largely on luck. While much of the story Hastings tells is inevitably focussed on the actions of the Royal Navy he does not forget the stoicism and courage of the seamen serving on the merchant ships of the convoy: ships that lacked the speed, firepower and armoured protection of their naval escorts. As he points out, those serving in the Merchant Marine suffered a bigger percentage casualty rate than either their Royal Navy colleagues or those serving in the Army.

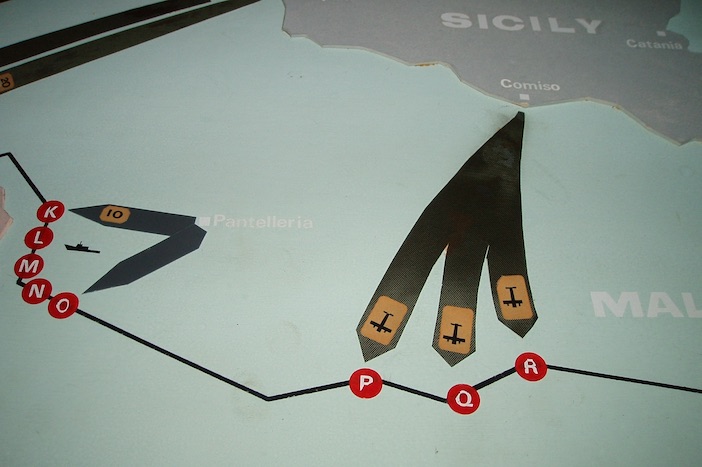

HMS Manchester hit at position K during Operation Pedestal (photo: National War museum, Valletta, Malta)

The first attack on the convoy came without warning on the 11th August. A German U-boat managed to penetrate the defensive screen of destroyers and get to the heart of convoy where it was able to identify one of the carriers – HMS Eagle – and fire four torpedoes into its port side. The damage was catastrophic. Within four minutes the ship had capsized and sunk with the loss of 131 lives and 16 Sea Hurricane aircraft, almost a quarter of the aircraft available to help defend the convoy. This sinking was the single biggest loss suffered on Operation Pedestal but it was only the start.

In the four days that followed, the convoy and its naval escorts were subject to sustained attack from the air – on one occasion by nearly a hundred German and Italian aircraft – as well as from submarines and motor torpedo boats. Attacks were sudden and often from several directions at once. Hastings’ skill here is clear, penetrating the chaos of battle and the participants’ conflicting memories. As for the cost, the Navy lost a further three ships sunk in addition to the Eagle and five more seriously damaged but still afloat: of the fourteen merchant ships only five limped into Valetta harbour including the now much battered and under tow Ohio. But they were enough to save the island.

Hastings does not shirk from questioning whether the assembly of such a fleet containing so many valuable warships in order to shepherd a modest fourteen merchant ships to Malta was worth the operational risks involved and the inevitable cost in damaged ships and shattered lives. His answer is an unequivocal yes on two main counts. The first is morale. He stands with Churchill that the loss of Malta would have seriously damaged national morale after two years of seemingly endless failure and defeat from Narvik and Dunkirk to the fall of Singapore and Tobruk.

Hastings does not shirk from questioning whether the assembly of such a fleet containing so many valuable warships in order to shepherd a modest fourteen merchant ships to Malta was worth the operational risks involved and the inevitable cost in damaged ships and shattered lives. His answer is an unequivocal yes on two main counts. The first is morale. He stands with Churchill that the loss of Malta would have seriously damaged national morale after two years of seemingly endless failure and defeat from Narvik and Dunkirk to the fall of Singapore and Tobruk.

The second, and equally important, is strategic. The island was a vital base from which to attack German and Italian supply lines supporting their forces in North Africa. Between December 1942 and May 1943 air and sea forces based on the island sank some 230 German and Italian ships. Loss of the island would not only have enabled the Axis to improve logistic support for their forces in North Africa and improve their chances of success against the British 8th Army but would also have severely restricted the movements of Allied shipping and forced the Allies to recapture the island before they could consider invading Sicily and mainland Italy.

This is another good book to add to the long list Hastings has already written. He tells this exciting story in the lucid and accessible style that makes his books so readable. As ever, technical matters are clearly explained and kept free from unnecessary jargon and there are penetrating insights into the nature and conduct of war. There is certainly no need to have any prior knowledge of matters nautical and anyone reading the book will soon acquire a deep appreciation of the challenges faced by those who served at sea during the Second World War. Operation Pedestal also makes a good starting point for anyone wishing to begin learning about the war at sea. I heartily recommend it.

Operation Pedestal by Max Hastings is published by William Collins. Hardback RRP £25. For more information, please visit www.williamcollinsbooks.co.uk.

Header photo: Tal-Mixta Cave, Nadur, Malta by Stephen Lammens on Unsplash