Robert Harris has the knack of finding interesting historical individuals or events around which to build a riveting story. Their range extends from his first novel, Fatherland, his story based on a successful German invasion of Britain in 1940, to his superb three-volume life of Cicero, to an atmospheric re-telling of the hunt for the regicides of King Charles I in Act of Oblivion. Now, in Precipice, he recreates the affair between Herbert Asquith, the 61-year-old Prime Minister and father of five and the attractive 26-year-old socialite, Venetia Stanley.

The affair began in 1912 when they met on a yacht in the Mediterranean and lasted until mid-1915 when Venetia Stanley married. It was an affair conducted mostly, but not exclusively, by letter, of which some 700 of Asquith’s survive. In an unusually cautious act, given the indiscreet behaviour he increasingly exhibited during the affair, Asquith destroyed all the letters he received from Venetia Stanley. She, however, kept all of his.

The result is a one-sided treasure trove that Harris exploits to good effect. We may not hear Venetia Stanley’s voice in her own words but the tone that Harris gives her reflects what is known of her character – self-assured, measured, independent and intelligent. Where Asquith is concerned, we not only have a direct insight into the depth of his obsession with Stanley, but also into the business of state during a tempestuous period. Many of his letters provide the only record that exists of important government meetings as well as comments on political colleagues and extracts from confidential documents and telegrams. Sometimes Asquith would read the contents of a document to Venetia Stanley during one of their meetings in a car before tossing the crumpled paper carelessly out of a window. Harris exploits this as a way of introducing the fictional character of Police Detective Paul Deemer, the detective entrusted with investigating the source of the leaked documents when some of them are handed in to the police.

The result is a one-sided treasure trove that Harris exploits to good effect. We may not hear Venetia Stanley’s voice in her own words but the tone that Harris gives her reflects what is known of her character – self-assured, measured, independent and intelligent. Where Asquith is concerned, we not only have a direct insight into the depth of his obsession with Stanley, but also into the business of state during a tempestuous period. Many of his letters provide the only record that exists of important government meetings as well as comments on political colleagues and extracts from confidential documents and telegrams. Sometimes Asquith would read the contents of a document to Venetia Stanley during one of their meetings in a car before tossing the crumpled paper carelessly out of a window. Harris exploits this as a way of introducing the fictional character of Police Detective Paul Deemer, the detective entrusted with investigating the source of the leaked documents when some of them are handed in to the police.

As with so many of his books Harris intertwines fact and fiction into an engaging story. In Precipice he captures the social atmosphere of the unusually hot English summer of 1914 as both rich and poor entertained themselves, the former at house parties and summer balls, the latter mostly in the confines of the narrow, terraced streets that dominated Britain’s industrial cities. Both were equally ignorant of, let alone attentive to, the catastrophe that was developing in the Balkans. Harris captures, too, the sudden change of mood as the crisis spreads and Asquith and his cabinet must start facing up to the possibility of a European-wide war. Meanwhile, the correspondence between Asquith and Stanley not just reveals their increasingly obsessive relationship, although the obsessiveness is mostly on the part of Asquith, but also illustrates the changing political temperature as war first beckons, becomes a reality and starts to dominate everything.

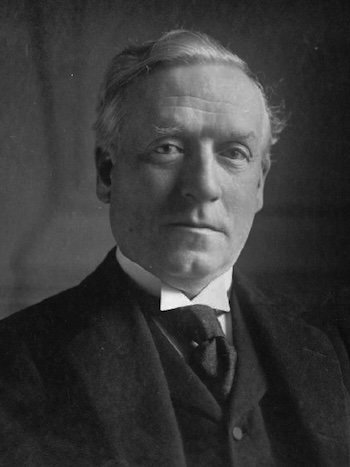

HH Asquith (image courtesy of WikiCommons)

The indiscretion displayed by Asquith in the run-up to the declaration of war with Germany in August 1914 and in the conduct of the war until almost mid-1915 is quite extraordinary and no minister of government, let alone prime minister, would be able to get away with such behaviour today. Whether his affair had any practical impact on his political behaviour and decision-making in government is unlikely. If anything, the picture that Harris paints is of a relationship which provides an escape from the pressures and claustrophobia of high office; Stanley as the only person with whom he can be completely open and unguarded in conversation and upon whom he comes to depend more and more; hence his increasingly obsessive behaviour. Asquith was, in any case, for all his intellectual abilities, not a dominating leader and certainly not of his cabinet with its fill of strong and ambitious characters, not least Lloyd George. It should not come as a complete surprise that in 1916, he was replaced as Prime Minister in a cabinet coup. By then he had been PM for eight long years and no longer had the energy or decisiveness needed to run a country at war.

Whether the affair was ever fully consummated is unclear. Lady Diana Cooper, one of Stanley’s best friends, believed, despite the effusion of some of the letters, that it remained platonic. Harris takes the opposite view and Asquith certainly had a reputation as a lady’s man. Whatever the truth, in Harris’s telling of the affair, Venetia Stanley certainly emerges in a better light than Asquith. She was certainly more self-aware. Choosing always to travel third class when going by train may seem faddish but it was also a sign that she did appreciate how privileged and isolated she was from most of the population. The attraction of Asquith also started to wear a little thin not just because of his increasingly obsessive behaviour but also because she felt the need to contribute to the war effort when so many of the male members of her family and friends were in uniform.

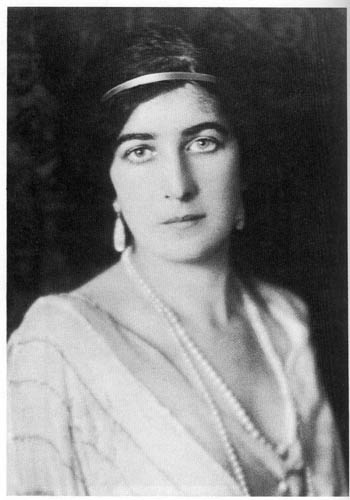

Venetia Stanley (image courtesy of WikiCommons)

Her first step was to volunteer to train as a nurse so she could help care for wounded soldiers. This did not stop Asquith from visiting her in the hospital where she was training, much to her embarrassment, or bombarding her with 147 letters in the three months of her training course. Her second step, far more dramatic from a personal point of view, was to agree in April 1915 to marry, at short notice, the physically unprepossessing but wealthy Edward Montagu, whose first proposal in 1913 she had turned down. Stanley broke the news to Asquith in early May and the wedding took place in July. She was clearly not in love with Montagu but the marriage at least ensured her escape from Asquith.

We are perhaps familiar with the privileged life style of the social and political elite of the time – a seemingly endless round of house parties and dinners London clubs or grand houses. Asquith’s wife seems to have spent most of her day organizing guest lists and menus. Harris also, though, captures the down to earth reality of a hospital in London at war and the life of those who worked below stairs in those grand town and country houses – it was a world the war would put into terminal decline.

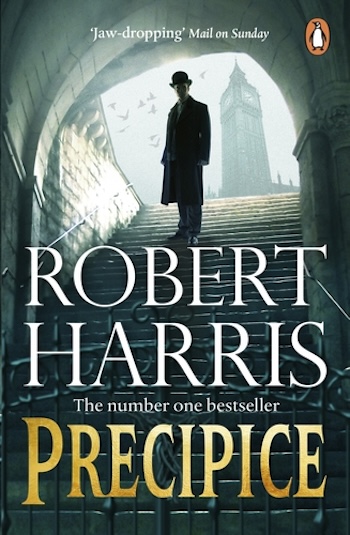

Precipice by Robert Harris is out now in hardback, published by Penguin. For more information, please visit www.penguin.co.uk.