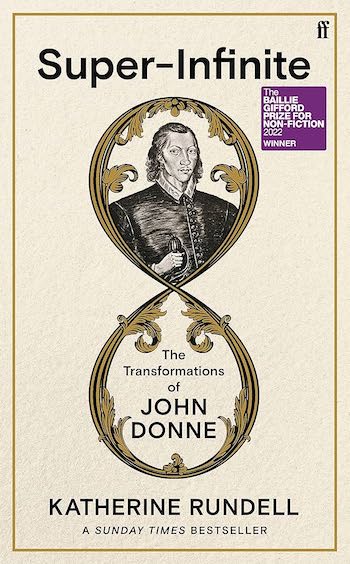

Super-Infinite is a startlingly wonderful and quite unputdownable biography of John Donne. Katherine Rundell has written a book that illuminates and entertains. It is a delight to read. She not only brings to life the complex character that is Donne, the depth of feeling and wit of his poetry and prose but also enters the social and political labyrinths of Renaissance England that a man of his frequently unconventional views had to learn to navigate with care. Almost every page brings with it a memorable and thought-provoking phrase. Rundell is a full-throated evangelist for Donne, which she openly declares in her introduction. However, she does not allow her evangelism to get in the way of her judgement.

The picture she has drawn of Donne shows him, warts and all, not that he had many as his portraits illustrate. Where there are academic boxing matches to referee over interpretations of aspects of his life and works, to borrow her description, her judgements are measured. When she ventures into literary criticism she does so by focusing on the work and explaining why he deserves his reputation as the greatest of the metaphysical poets as well as being the greatest love poet in the English language. In doing so, she avoids imposing any pre-conceived ideological framework as seems to be the fashion elsewhere. In short, she brings both Donne and the different country that was the England in which he lived vibrantly alive.

The picture she has drawn of Donne shows him, warts and all, not that he had many as his portraits illustrate. Where there are academic boxing matches to referee over interpretations of aspects of his life and works, to borrow her description, her judgements are measured. When she ventures into literary criticism she does so by focusing on the work and explaining why he deserves his reputation as the greatest of the metaphysical poets as well as being the greatest love poet in the English language. In doing so, she avoids imposing any pre-conceived ideological framework as seems to be the fashion elsewhere. In short, she brings both Donne and the different country that was the England in which he lived vibrantly alive.

The biggest and most dangerous obstacle that Donne had to navigate came early and was an accident of birth. He was born in 1572 into a well-known Catholic family at a time when being a recusant Catholic was increasingly dangerous. As Rundell comments ‘to be born a Catholic was to live with a constant low-level background thrum of terror’. The Papal Bull of 1570 which had excommunicated Elizabeth I as well as releasing her subjects from any allegiance to her had only raised the temperature still further, especially as it was followed by the Ridolfi (1571), Throckmorton (1583) and Babington (1586) plots against her, all involving Catholic agents and sympathisers. The last of these plots resulted in the execution of Mary Queen of Scots.

As a young boy Donne would have been well aware of the difficulties. His great-uncle Thomas had been outed as apriest in 1574 and was probably executed; Donne was taken at the age of 12 to visit another uncle, Jasper, in prison inthe Tower before he was exiled; worst of all, perhaps, when Donne was 21, his nineteen-year-old brother Henry died of the plague soon after he was imprisoned in Newgate Prison for sheltering a Catholic priest. The priest was hung, drawn and quartered.

Being a Catholic also meant that when Donne was sent to Oxford as a young teenager to study – this was not unusual then – he was unable to complete his degree because as a Catholic he could not swear allegiance to the Church of England. He then studied at Cambridge for three years despite being unable to acquire a degree there either due to the same obstacle. From Cambridge he moved to one of the Inns of Court. It was here that Rundell suggests his extraordinary literary talents exploded into view. Lincoln’s Inn was the perfect environment for a man like Donne to flourish, given his quick wit, whether ironic, satirical or just playful, his energy and vivacity and his command of the social graces.

The Great Hall of Lincoln’s Inn (photo courtesy of Creative Commons)

The Inns of Court did not merely train young men to be lawyers; most of them never intended to practise. It was a place where the clever and ambitious prepared themselves to climb the greasy pole of a Renaissance court where the ability to amuse and entertain with wit and intellectual ingenuity were as important as any professional qualification. As for the social graces the capacity to write a verse of poetry was just as important as being able to dress well and show a leg on the dance floor. Donne was clearly a party animal, a sharp lawyer and a master of all those social graces. The famous Lothian portrait of him illustrates that he knew, as Rundell points out, that “the beautiful are rarely beautiful without effort”’. It comes as no surprise he was chosen by his colleagues at the Inn as their Master of Revels.

The poetry of Renaissance England was alive with satire, love and courtship, paradoxes, elegies and epigrams. Metaphor was not only used for flattery and seduction but also as a way of making sarcastic and disparaging comments about religion and politics without attracting the ire of the censor and the might of Crown and Church. Donne was a master of the “careful shield of metaphor”, as Rundell notes, whether in the service of love, satire or paradox, and Donne was an expert at all three. As for love, despite being the young man about town that he was, Randall’s chapter heading “the inexperienced expert of love” is closer to the truth than his poems would suggest.

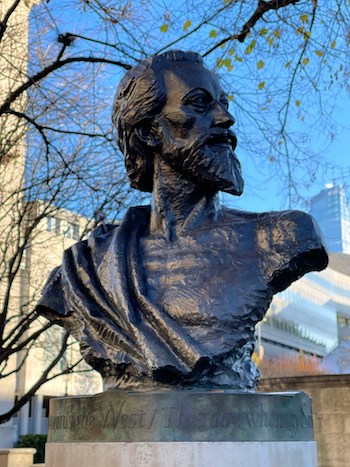

John Donne Memorial (2012) by Nigel Boonham in St Paul’s Cathedral Churchyard (Photo by Bill Eccles, courtesy of Unsplash)

Donne was highly regarded as a poet in his lifetime, even though he never published a book of verse. His poems, in hand-written copies, were passed around the underground market that existed at the Inns of Court and elsewhere, rather like bootleg music editions or Soviet samizdat. The copies and the copying spread like wildfire. This explains why, given that only eight of his poems were printed in his lifetime, so many have survived. It was not until two years after his death that the first printed edition of his poems was produced. Ever since, with the exception of Victorian respectability, his poems have been included in any anthology of English poetry worth its salt.

All was not wit, word games and eroticism. There is also a darkness that appears in Donne’s writing, sometimes linked to bodily corruption and death, sometimes even cruel and misogynistic. Certainly, over half of his Songs and Sonnets make some reference to death. It is difficult to be precise where this comes from: whether it was just always part of his character; whether it was the circumstances of his upbringing in a recusant Catholic family with members imprisoned, executed, and exiled; or whether it was the closeness of death, not least because, to paraphrase Rundell, plague was an ever-present hunter stalking the city of London. Indeed, it was said to be not uncommon for a man “to dine with hisfriends and sup with his ancestors”.

Building a career as a known Catholic, even if an increasingly lapsed one, remained a challenge as Donne set out to find a patron who might provide employment. His search saw him involved in two naval expeditions against the Spanish in the 1590s. It was after the second of these adventures that he secured an appointment as a secretary to Sir Thomas Egerton, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal as well as a senior law officer in his capacity as Master of the Rolls. It would seem Donne had landed on his feet. But all came crashing down, not because of his Catholic heritage, but because of love and marriage.

He fell for his employer’s fourteen-year-old niece and married her in secret four years later. The risks for both of them were great given that marriage was so important in advancing the wealth and status of a family. The consequences for his career were immediate and dire once the marriage became public knowledge. The lawyer who supplied the licence, the priest who officiated and Donne himself all found themselves imprisoned. The marriage was eventually accepted as legal but Donne was sacked from his employment, could find no new patron and ended living in relative penury with his wife and their growing brood of children as he scratched a living from writing and legal work while often living in the houses of and with the money of friends. It was not until fourteen years later and his ordination, encouraged by King James I, that he was able to build a new and successful career in the Church of England, becoming the Dean of St Paul’s and the most sought-after preacher in the kingdom. People came in their thousands to hear him speak. It was said that when he spoke he could charm men’s souls.

John Donne’s house in Pyford, Surrey (photo courtesy of Creative Commons)

The debate about Donne that causes the fiercest of academic boxing matches is at what point did Donne, the recusant Catholic, convert to the Church of England and, hierarchy and politics apart, its Calvinist approach to theology (not that he was ever a systematic theologian). As to his motives, was it a genuine conversion or merely a pragmatic adjustment to further his career? Rundell takes a measured view. Her answer to the first is that there was no Pauline conversion on the road to Damascus but a slow march, step by step, that was advanced enough by 1601 for him to have a Church of England marriage. That said, it was not until 1615 that he became ordained. As for motive, she suggests he became increasingly disenchanted by what he came to see as Jesuit extremism after the death of his brother. His love for Anne More and his desire to marry her may also have played their part.

The descriptive and witty chapter headings that Rundell has deployed encapsulate her style as well as capturing the changing temper of Donne’s character and life. They range from Hungry Scholar and Erratic Collector of His Own Talent to How to Pretend to Have Read More than You Have. I can think of no better way to approach John Donne’s poetry and his extraordinary life, whether for the first time or for a long-delayed return visit, than by reading this eloquent, hugely enjoyable, and scholarly biography. If it does not encourage a visit to Donne’s poetry then I fear that nothing will.

Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne by Katherine Rundell is available now in all good stockists, published by Faber. Katherine Rundell is a Fellow of All Souls College, Oxford. Her bestselling books for children have been translated into more than thirty languages and have won multiple awards. Her most recent novel, Impossible Creatures, was named Waterstones Book of the Year for 2023.

Header photo by Sergiu Valena (courtesy of Unsplash)