Christmas wouldn’t be Christmas, at least in more normal times, if a production of A Christmas Carol wasn’t on in a theatre near you. No other novel has been adapted and performed so frequently. Indeed, the novels of Charles Dickens have been transferred to stage and screen more than those of any other novelist and the list continues to grow. Last year saw a much praised new film version of David Copperfield (the ninth) and this Christmas there is not only a new film of A Christmas Carol (the twentieth) but also a big stage production, albeit with an empty auditorium, being live-streamed from the Old Vic theatre.

Despite the huge success Dickens enjoyed during his lifetime, the popularity that many of his novels still continue to enjoy and the extent to which so many of his characters have entered popular culture – even when not always recognised – he is nonetheless often derided by some as a mere entertainer: too sentimental, too carnivalesque and full of caricature, too lacking in the psychological depth of a Dostoyevsky or a George Eliot. Professor John Mullan’s new book, The Artful Dickens, illustrates in great depth why Dickens is so much more than just a mere entertainer, although hugely entertaining he most certainly is.

Despite the huge success Dickens enjoyed during his lifetime, the popularity that many of his novels still continue to enjoy and the extent to which so many of his characters have entered popular culture – even when not always recognised – he is nonetheless often derided by some as a mere entertainer: too sentimental, too carnivalesque and full of caricature, too lacking in the psychological depth of a Dostoyevsky or a George Eliot. Professor John Mullan’s new book, The Artful Dickens, illustrates in great depth why Dickens is so much more than just a mere entertainer, although hugely entertaining he most certainly is.

Mullan’s approach is to identify, in the words of his subtitle, The Tricks and Ploys of the Great Novelist that reveal what an accomplished master of language and story-telling Dickens is. However, this is no piece of indigestible, jargon-filled modern literary criticism but a superb work of literary detection that should, I hope, encourage many to return to the well of Dickens’ imagination for further refreshment.

Professor Mullan’s approach is best illustrated by his chapter headings. They range from Smelling, Haunting, Laughing and Drowning to Naming, Speaking, Changing Tenses and Breaking Rules. There is also Knowing about Sex – and this reveals Dickens at his most uncertain, even evasive and prim, and influenced by the conventional Victorian view of woman as ‘the angel in the house’ epitomised by Little Nell in The Old Curiosity Shop. Dickens, the radical social reformer, has vanished and women who stray from the path of Victorian respectability, like Lady Dedlock in Bleak House, are doomed to unhappiness.

Dickens loved performing and was as skilful and enthusiastic a magician as he was an actor, as clearly emerged in the sell-out public readings of his stories – in reality, more like dramatic performances – when Dickens went on tour in Britain, America and Europe. This sense of drama is even reflected in the time he spent developing the names of his characters. Dickens often started work on a new novel by choosing the names of his leading characters and this became an essential part of identifying their nature and situation as well as for making some moral point. In Great Expectations Miss Havisham’s name – “have is sham” – not only makes the point that wealth does not of itself bring happiness but also encapsulates her situation.

Dickens loved performing and was as skilful and enthusiastic a magician as he was an actor, as clearly emerged in the sell-out public readings of his stories – in reality, more like dramatic performances – when Dickens went on tour in Britain, America and Europe. This sense of drama is even reflected in the time he spent developing the names of his characters. Dickens often started work on a new novel by choosing the names of his leading characters and this became an essential part of identifying their nature and situation as well as for making some moral point. In Great Expectations Miss Havisham’s name – “have is sham” – not only makes the point that wealth does not of itself bring happiness but also encapsulates her situation.

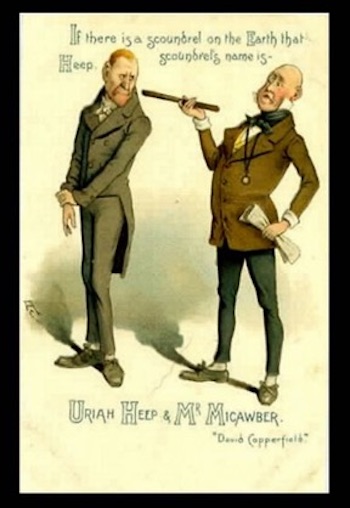

Before he settled on Copperfield for David Copperfield he tried a long list of other possibilities ranging from Trotbury to Flowerbury and Copperstone. Was he after something that sounded gentlemanly but not forceful? It is hardly a surprise to discover that Dickens has provided more eponyms – words derived from the names of characters – than any other English novelist: Bumble, Pickwick, Gradgrind, Heep, Micawber, Pecksniff and the Artful Dodger – not forgetting the most obvious and well known of them all. Scrooge.

Professor Mullan also shows how Dickens used speech mannerisms to identify his characters. Given almost all his books were published in monthly instalments, this helped his readers immediately recognise the various characters, especially if they had been absent from a number of instalments. Right from the start of his career, Dickens was fascinated by performers who could “do” different voices and by individual idiosyncracies of expression. In Pickwick Papers, Sam Weller always transposes “v” and “w”: “vy that’s just the wery point”. InNicholas Nickleby Mr Mantolfini is immediately recognised when he says “Oh demit”. Dickens knew that speech was not just a matter of words and sentences but also non-verbal mannerisms. There is the deferential cough of Mr Tulkinghorn, the lawyer in Bleak House, when faced with his wealthy clients; or the rebellious lisp of Mr Sleary, the circus master in Hard Times, when confronted by the over-bearing Mr Gradgrind.

Professor Mullan also shows how Dickens used speech mannerisms to identify his characters. Given almost all his books were published in monthly instalments, this helped his readers immediately recognise the various characters, especially if they had been absent from a number of instalments. Right from the start of his career, Dickens was fascinated by performers who could “do” different voices and by individual idiosyncracies of expression. In Pickwick Papers, Sam Weller always transposes “v” and “w”: “vy that’s just the wery point”. InNicholas Nickleby Mr Mantolfini is immediately recognised when he says “Oh demit”. Dickens knew that speech was not just a matter of words and sentences but also non-verbal mannerisms. There is the deferential cough of Mr Tulkinghorn, the lawyer in Bleak House, when faced with his wealthy clients; or the rebellious lisp of Mr Sleary, the circus master in Hard Times, when confronted by the over-bearing Mr Gradgrind.

Dickens was most certainly in the vanguard of opinion when he set out to expose so many of the social ills that accompanied the rapid urbanisation and industrialisation of England as it became the “workshop of the world” in the mid-19th Century. Less well known are his innovations in novel writing. Professor Mullan examines these in his chapters on changing tenses and breaking the rules. In his last three novels, starting with Bleak House, Dickens experimented with time changes by alternating past and present tenses, enabling him to create a greater sense of uncertainty and immediacy for his characters.

Anthony Trollope described Dickens’ style as ‘jerky, ungrammatical and created by himself in defiance of the rules’. Dickens would not have minded this criticism any more than his vast array of readers did. He relished the use of repetition and lists, endless lists, because of the rhythm they gave especially when read aloud in performance. A wonderful example is to be found in Little Dorrit illustrating the hopeless and shiftless working life of Amy Dorrit’s brother Tip as he drifts through some twenty jobs starting in a warehouse and ending in the docks having passed through Billingsgate, a distillery, a number of law offices and an auctioneers on the way.

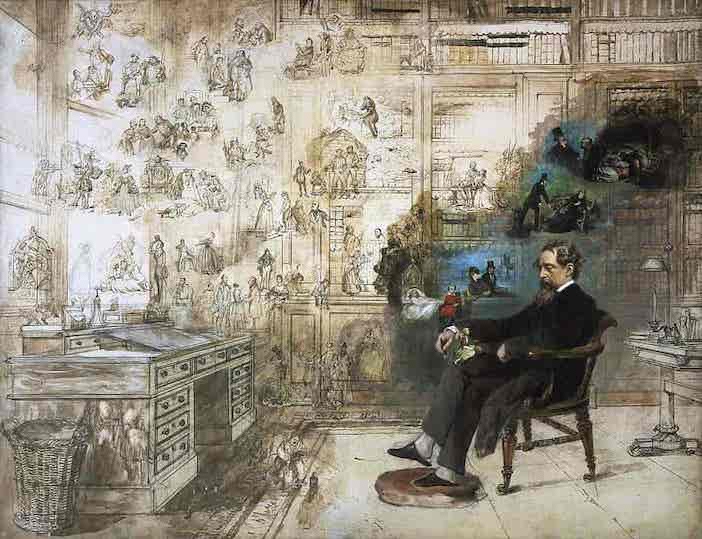

‘Dickens’s Dream’ by Robert William Buss (Charles Dickens Museum, London)

There is much to enjoy in this enlightening and entertaining book, not least in the chapter on laughing – Dickens had a natural comic ear. Professor Mullan not only makes clear why Dickens’ novels have been transferred so often to stage and screen – Dickens was a natural showman who understood what made good theatre – he also succeeds in giving the lie to the oft repeated accusation that his characters lack depth.

Most important of all The Artful Dickens opens the door to hours of pleasure reading the stories with a more informed and appreciative eye and in trying to unpick what lies behind the names of the vast array of characters that populate them, especially those to which Professor Mullan has not given the answer. For a lover of Dickens this book would make a wonderful Christmas present.

The Artful Dickens by John Mullan, published by Bloomsbury, is available from all good stockists, priced £16.99.