I must have on my groaning shelves three dozen biographies of Napoleon, but not one written by a woman – that is until now. Why might that be, I began to think as I opened this one that had landed on my desk, taking in the soft, velvety jacket cover along the way (how did they do that, some Chinese paper trickery)? But here one most certainly is, and by a formidable woman at that; a Doctor, Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, and a Cambridge academic: Ruth Scurr.

Author of near definitive biographies of John Aubrey and Robespierre, Dr Scurr has turned her forensic mind to one of the great historical enigmas, Emperor Bonaparte. As I sit to write this review, exactly 200 years since his death, a bitter debate rages about his invasion of Egypt and his merciless treatment of the indigenous population. But at the same time he undertook, in this expedition bent on a violent conquest, a massive study never attempted before or since to examine, deconstruct and quantify the entire history of the country’s culture, architecture, agriculture, horticulture, language and religion.

To this day the resulting document almost defies analysis and presents as one of the most formidable and comprehensive account of a country’s cultural, social and scientific history. This man, responsible for the death of millions, was according to Dr Scurr, a lover of nature, horticulture, botany, viticulture and, especially, silvology. Trees – and the planting of them – became his passion and in this unique and intriguing book, Dr Scurr traces the pattern of his astonishing achievements on the battlefield in parallel with another, as if with a stump of charcoal lodged behind his ear, he reaches with one hand to ignite a cannon whilst simultaneously the other clutches a hoe.

To this day the resulting document almost defies analysis and presents as one of the most formidable and comprehensive account of a country’s cultural, social and scientific history. This man, responsible for the death of millions, was according to Dr Scurr, a lover of nature, horticulture, botany, viticulture and, especially, silvology. Trees – and the planting of them – became his passion and in this unique and intriguing book, Dr Scurr traces the pattern of his astonishing achievements on the battlefield in parallel with another, as if with a stump of charcoal lodged behind his ear, he reaches with one hand to ignite a cannon whilst simultaneously the other clutches a hoe.

From the moment our infant Emperor could take account of his surroundings, he was involved in dealings with property and matters concerning agriculture and horticulture. His father was quite well off, not a Corsican peasant as inaccurate rumour might have us believe, and he successfully negotiated for acquisition and subsequent revival of a portion of land subject to flooding and “pestilence”. This resulted in a planting of literally thousands of Mulberry trees with the help of various government subsidies. However, the area appeared to be cursed, as disease continued to decimate the plantings, and it ruined Napoleon’s father financially leaving Napoleon, on his death, with an unwanted inherited debt. So, thus he stumbled, throughout his career, from muddy plantation fields to even muddier and bloodier battlefield ones. His bootmakers must have been overjoyed when yet another campaign or garden renovation loomed.

Dr. Scurr’s commanding research into her subject renders us Google-eyed devotees frankly speechless and is an object lesson in maintaining a balance between fact and narrative. My only criticism, if criticism at all as opposed to mere commentary, is that in the central section a succession of details, including names of architects and builders, tends to overwhelm pure storytelling. Here I am referring to Napoleon’s annexation of Italy and his seemingly endless attempts to reconstruct the buildings, monuments and gardens of Rome and environs dans le style francais.

Another observation, based on an accumulation of indicators throughout the text, is the fact that it is almost impossible at first to ascertain Dr. Scurr’s attitude towards her subject. This is unusual in biographies where an author ordinarily feels compelled towards, or away from, his or her subject based on a visceral emotion response, frequently either of love or hate. It is only through calling upon my deeper instincts when absorbing her narrative that I am left with the strongest of impressions that Dr Scurr actually, if not fully despising her subject, at least thoroughly disapproves of him; although this does not prevent her from complimenting his strengths, other than those on the battlefield which she assiduously avoids doing.

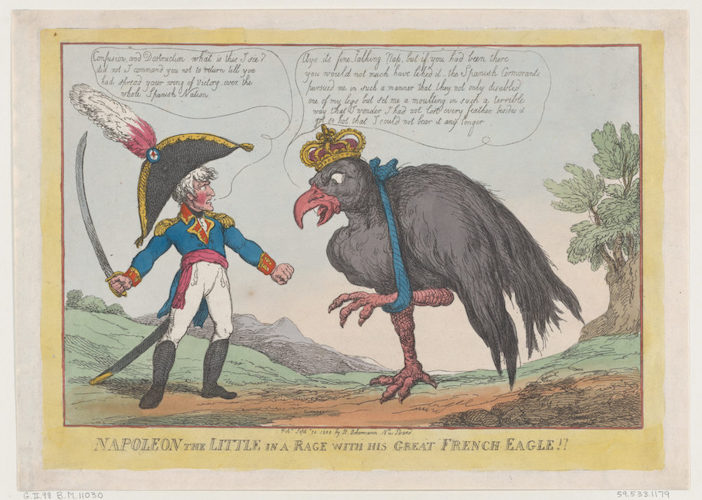

It is simply not possible to recognise here the greatest commander in the field since Hannibal. For such assertions you must look to other commentators. One thing that led me to my conclusion about Dr Scurr’s feeling to her subject is that she avoids anecdote and tittle-tattle, which usually provide a tasty sauce, making the whole meal more appetising. Such bon-mots also have the tendency to render the subject human (if not necessarily humane) and vulnerable to slings and arrows, but here this is decidedly not to be. We all secretly like to absorb a Daily Mail headline (how many lovers did he have, was he better in bed than Wellington, where did his meanness come from, did he make jokes or just tweak ears, et al). In this respect Dr. Scurr’s waterline rises well above such subterranean human foibles.

‘Defence of the Château de Hougoumont by the flank Company, Coldstream Guards’ (1815), by Denis Dighton

The description of Napoleon’s final battle, that of Waterloo, is also the most fully detailed, probably because it elides with her thesis of the central importance of gardens in the Emperor’s career. In this case it is the garden attached to the farmyard at Hougoumont, around which most of the fiercest fighting occurred. Wellington commanded the farmyard just moments before French troops attempted to do the same on the eve of the battle itself, and the Iron Duke made it clear that “he who retained Hougoumont would win the day.” In this prophesy he proved right, with corpses piled six to eight deep against the garden walls as the French tried time and again to take the building. It was probably best that Napoleon’s view of this slaughter was mercifully hidden from him by dint of both topography and canon smoke; for it surely would have reminded him of his deeply traumatic encounter with a wholesale massacre in the garden of the Tuileries which helped depose Louis XVI some thirty years earlier, and from which he never fully recovered.

In summary, this book is both beautifully written, as well as being a delight, both to botanists, horticulturalists, silvologists and, last but not least, Napoleonists. Her subjects are on a continuously rising scale – Aubrey, Robespierre, and now the creator of arguably the greatest democratic document ever conceived, the Code Napoleon. Intrigued and excited, we wait expectantly to see who possibly can be next.

‘Napoleon: A Life in Gardens and Shadows’ by Ruth Scurr is published by Chatto & Windus. It is available now in hardback from all good stockists, priced £30. For more information, please visit www.penguin.co.uk.

Header photo by Jeremy Zero (courtesy of Unsplash)