The publication of yet another book, even a short novel such as The Passenger, in the already crowded Holocaust field may seem one book too many for some readers. However, anyone who lets this book pass by will be missing a remarkable story that stands comparison with Hans Fallada’s Alone in Berlin and Irene Nemirovsky’s Suite Francaise. This is especially so in its evocation of the psychological impact of the Nazi terror. Not just about that impact on its Jewish victims but also on the behaviour of those caught by mischance in its claws. They might be ordinary citizens faced with the fearful consequences of associating with, let alone helping, a long-standing friend, colleague or customer who happened to be Jewish; or similarly ordinary citizens who chose to exploit the vulnerability of the victims for financial gain.

Ulrich Boschwitz, the author of this exceptional short novel, was only twenty-three when he wrote it in four intense weeks in November 1938 as a response to the brutal assault on the Jewish community in Nazi Germany that came to be known as Kristallnacht, the night of the broken glass, named for all the broken windows in Jewish shops, businesses and homes that came under attack.

The book was published in both England and France but with the outbreak of war in September 1939 and the death of the author in 1942 it disappeared until 2018 when the manuscript was rediscovered and it was printed in Germany for the first time. Despite being Jewish Boschwitz was interned in England when the war broke out and was then shipped out to Australia. Tragically, on his return journey back to England the ship on which he was a passenger was torpedoed by a U-Boat and sank with the loss of all on board.

The novel begins on the day in November 1938 that ended in Germany with Kristallnacht. Otto Silbermann, a Jewish businessman is hoping to leave Germany with his non-Jewish wife and join their son in France. He arrives home only to have Nazi thugs turn up at his apartment. He escapes from the building with the help of a non-Jewish colleague – a member of the Nazi Party who nonetheless gets beaten up by the thugs, in a case of mistaken identity. For many Jews attacked that night their beating was followed by arrest and imprisonment and for some torture and murder in the days that followed. For Silbermann it is the beginning of a nightmare. Germany has become one huge concentration camp and he gradually realises he has ‘become a business opportunity for his enemies and a danger to his friends’. His desperate attempts to escape by travelling endlessly and fruitlessly all across Germany by train form the heart of this story.

The nightmare of The Passenger is Kafkaesque in its intensity and frequently illustrates with uncanny prescience so much that was to follow for those Jews who failed to escape from Germany before the Final Solution gathered full speed. A waiter declares ‘the best would be if Jews had to wear a yellow band on their arms. Then at least there wouldn’t be any confusion’. At one moment Otto reflects, ‘perhaps they’ll slowly undress us first and then kill us, so our clothes won’t get bloody and our banknotes won’t get damaged.’ At another he remarks: ‘These days murder is performed economically.’ For someone writing in 1938 this is extraordinary.

The nightmare of The Passenger is Kafkaesque in its intensity and frequently illustrates with uncanny prescience so much that was to follow for those Jews who failed to escape from Germany before the Final Solution gathered full speed. A waiter declares ‘the best would be if Jews had to wear a yellow band on their arms. Then at least there wouldn’t be any confusion’. At one moment Otto reflects, ‘perhaps they’ll slowly undress us first and then kill us, so our clothes won’t get bloody and our banknotes won’t get damaged.’ At another he remarks: ‘These days murder is performed economically.’ For someone writing in 1938 this is extraordinary.

Otto Silbermann ends up without any money and under arrest. He is one of the unlucky 30,000 arrested as part of or during the aftermath of Kristallnacht. That said, of the 500,000 or so Jews in Germany in 1933 – less than 1% of the population of Germany – only some 200,000 remained in Germany when war broke out in 1939. Escape was frequently difficult but never completely impossible. Money certainly helped. As Otto Silbermann comments ‘to make it out of here you have to leave your money behind, and to be let in elsewhere you have to show you still have it’. A chilling Catch-22! Ulrich Boschwitz, his mother and sister escaped from Germany early on. His sister emigrated to Palestine in 1933 not long after the Nazis came to power; Ulrich and his mother went to Sweden in 1935 after the publication of the Nuremburg Race Laws that, in addition to defining who was a Jew, also removed German citizenship from the Jewish population of Germany.

This book, the second written by a very young man, is a worthy addition to the literary bibliography of the Holocaust. It has a straightforward readable style that moves at the pace of the trains on which its protagonist travels. The writing is occasionally a little clumsy but for me, that is a reflection of the speed and passion with which it was written and the youth of its author. This is a minor caveat that I hope will deter no one from reading this remarkable short novel.

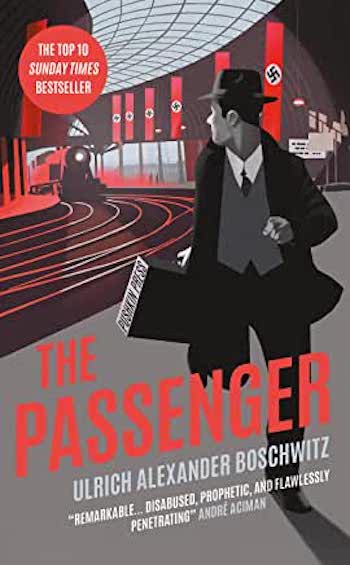

The Passenger by Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz, published in hardback by Pushkin Press, priced £14.99. For more information, please visit www.pushkinpress.com.