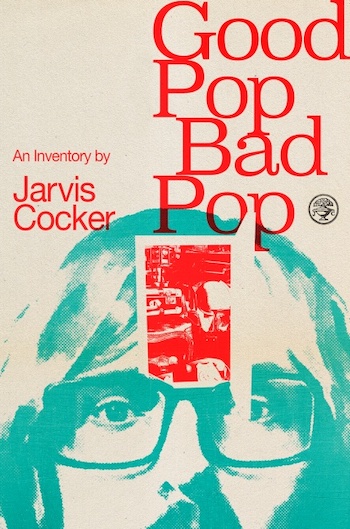

Jarvis Cocker wanders on to the stage looking more like a geography teacher than a pop star, dressed in a relaxed wool jacket, checked shirt, jeans and deck shoes and carrying a black bin liner filled with, well, we shall see. He’s accompanied by Miranda Sawyer, who’s about to interview him as part of Southbank Centre’s Summer Literature Season on the subject of his new book, his first in long-form prose, Good Pop, Bad Pop.

Judging by the lengthy and enthusiastic applause, the audience is delighted to see him. After all, there’s a pop poet in our midst. Cocker is no stranger to the Southbank Centre, having curated the Meltdown Festival in 2007, but he’s probably better known for being the frontman of the hugely successful and much-loved group Pulp, which he founded while still at secondary school in 1978.

Cocker explains that he knew from a very young age that he wanted to form a band and it would be called Pulp, partly because, as we’re soon to discover, he’s always been fascinated by pulp: pop, pulp fiction, trash. And, indeed, the premise behind the book is what if the objects we keep hidden say more about us than those we put on display.

Cocker explains that he knew from a very young age that he wanted to form a band and it would be called Pulp, partly because, as we’re soon to discover, he’s always been fascinated by pulp: pop, pulp fiction, trash. And, indeed, the premise behind the book is what if the objects we keep hidden say more about us than those we put on display.

Cocker explains that the idea for Good Pop, Bad Pop began five years ago when he had to clear his belongings from a loft in East London. He’d moved to the city from Sheffield in 1988, initially into a squat and then various other abodes, never questioning why he was carrying around the debris of his past from one address to the next, then shoving it all into the loft of each. It turned out, he says, that “the objects told me my life story, but in a way I wasn’t expecting”. The collection, he adds, begins when he was very young and ends before he moved to London. And the decision he had to make with every item was whether to keep or cob (throw). What we’re about to be shown is from the keep pile.

Cocker leans forward in his seat, feels into the bin liner and pulls out object number one: a notebook. The stamp on the cover (a camera magnifies each item onto an overhead screen) is printed with the words Science Book No 4 and the name C Hoyland written neatly above that suggests it must have belonged to his mother at one point, he explains. Judging by the words PULP scribbled five times in capitals further down, it was then acquired by her son.

Inside he has written: “Most groups have a certain mode of dress, which is invariably emulated by their followers. The Pulp Wardrobe shall consist of:

Duffle coats (preferably blue or black).

Crew-neck jumpers (of the ‘rancid’ C&A type, or of woollen or cotton construction).

Garishly (preferably day-glo) coloured T and sweat shirts, preferably of an abstract design…”

The list also includes “rancid” ties, drainpipe or tapered trousers, pointy boots, Oxfam jackets, silly socks, “hair shortish (not skinhead)” and “no sequins unless for silly purposes”. On the following page, all this is illustrated. “Not practical stage wear,” concedes the modern-day Cocker, acknowledging that duffle coats and crewe-neck jumpers could get a bit hot under studio lights, but this was his “mission statement, written before I even had a band”. The detail is certainly impressive.

The second object to be pulled from the bin liner is a Gold Star polyester and cotton yellow shirt with white spots from a jumble sale. “I thought: ‘This is me from now on,’” explains Cocker. “It cost 10p or something like that.” Sawyer adds: “It’s sad that you can no longer rock up on Top of the Pops in second-hand clothes, or whatever you’d been wearing all day.” They agree that everything now is massively styled, a real production. “I watched The Brits on TV recently,” says Cocker. “And I thought, ‘What’s going on here?’”

It should be mentioned at this point, as they do, that punk was a game-changer. “Everything was wide before punk,” says Cocker. “Wide, flared trousers, wide collars and so on. Then punk arrived and everything got thin.” Which takes us back to his fashion notes: garish T-shirts, pointy boots, drainpipe trousers and short hair. And for the first time, anyone who could play three chords could form a band. What mattered was no longer what you sounded like but what you were singing about, music to the ears of a boy who’d bought a Beatles songbook only to be dismayed by how many chords were in it.

Other objects drawn from the bin liner include broken glasses (it turned out to be a myth – even to Cocker himself – that it was the meningitis he’d contracted as a child that had affected his eyesight). Many pairs of specs had been crushed underfoot first thing in the morning when he couldn’t see more than nine inches from his face. He adds that he didn’t have glasses until he went to school and wonders if the first few years spent being able to see only what was right in front of him resulted in him paying such great attention to detail.

A John Peel Roadshow ticket for Sheffield Polytechnic (price 50p) is another item. The event happened to take place three weeks after Pulp had recorded their first demo tape and when he saw his chance at the end of the evening Cocker shyly gave a copy to Peel. Within weeks, just before his 18th birthday, Cocker received a call from the BBC asking if Pulp would like to come to the studio and record a John Peel session. “The manifesto had come true,” he says.

The final object is a nightclub pass. While his friends went off to university, Cocker stayed in Sheffield and attended the University of Disco, more specifically the Limit nightclub, and here he learned to dance without caring what he looked like, later the basis for his stage moves. “Choreography was not involved.”

Cocker goes on to tell the story of his fall from a high window in an attempt to impress a girl. It ended with him spending two months in hospital while his broken bones healed. As he finally left the hospital, felt the fresh evening air on his face and saw the lights of Sheffield twinkling before him, the penny dropped – his search for inspiration was complete. Or as he puts it in the book: “I now realise that I’d been surrounded by inspiration all along. Only I’d been too intent on scanning the distant horizon to actually see it. Now that I was back down at ground level and staring life fully in the face I found myself eyeball to eyeball with what I’d always been searching for: something to write about.”

After a Q&A session, Cocker is available to sign copies of his book somewhere near the main bar downstairs. My friend and I head towards the bar so I can have my copy signed. The queue resembles Heathrow airport security at the height of summer: hundreds of people snaking towards a desk. We decide to relax with a glass of wine and wait for the queue to subside. Then we have a second glass. By 11 o’clock there are still a couple of hundred people clutching their books. I decide Cocker has been patient enough – he’s been personable and devoid of ego all evening, so will probably be polite and pretend to be pleased to meet me, but I decide instead to be the owner of a rare, unsigned copy and we head off into the night.

Good Pop, Bad Pop by Jarvis Cocker is published by Vintage Books (£20). For more information about the Southbank Centre Summer Literature Season, please visit www.southbankcentre.co.uk.

Photographs by Pete Woodhead, Southbank Centre