Following its critically-acclaimed 2022 festival, Glyndebourne takes its productions on tour with the new La Boheme and a revival of Michael Grandage’s definitive Marriage of Figaro. Ahead of the opening night, Larry gets into the swing of things chatting to lead soprano Soraya Mafi as she prepares to take to the stage as Mozart’s lovable maid…

Soraya, this is very exciting indeed. I’ve been longing to see Grandage’s Figaro. What are you looking forward to most about the performance, is there a particular aria?

There are two moments which are my absolute favourite; Susanna’s aria in Act IV, Deh Vieni, Non Tardar. It’s beautiful because Susanna is a very busy woman – it’s the longest role in opera – she’s virtually always on stage, everything she’s doing serves a purpose, but she’s not had her moment to shine. Then, in Act IV, she gets her moment, she has the last aria before the finale. Mozart saves her opportunity right to the last point. She’s in the garden, there’s disguises and mistaken identity going on, she and the Countess are trying to trick Figaro and the Count, who’s been messing them around, and then this aria comes; at first she’s trying to annoy Figaro but eventually it turns into a wonderful love song. It’s a really simple melody, but is actually very difficult to sing…

Soraya Mafi as Susanna with Nardus Williams as Countess Almaviva and Alexander Miminoshvili as Figaro. © Glyndebourne Productions Ltd. Photo by Richard Hubert Smith.

How is that?

Often the most simple-sounding songs are the most difficult because there’s no room for error. On top of that you’ve been singing for nearly three hours, so you’re pretty tired, you’ve got to pace yourself, and it’s very exposed. But it is so, so beautiful.

There’s also a moment in Act III, the sextet. It’s just after – sorry, this is a spoiler…

Don’t worry, I suspect people know the story!

Ha, well, it’s after it’s just been revealed that Figaro is the son of Dr Bartolo and Marcellina. Susanna comes in and sees Figaro hugging Marcellina and Susanna thinks he’ll leave her, but then she figures out what’s happened. It’s a clever, brilliant piece of music, threading the storylines of each character, and the way Mozart wrote it, it’s really funny, and loving; it’s one of my favourite moments in opera. I’ve done the role a few times now and it still makes me laugh.

There’s the famous duet as well, isn’t there?

The Sull’aria. Yes, it’s beautiful. And, again, it’s very difficult to sing because the melody changes between the Countess and Susanna, so you’re trying to match each other while trying to allow your voice and your character’s personality to shine through. I don’t know whether I’ll look forward to that; I’m always anxious that the audience knows it and expects this big moment!

In the run up to this, with today being the first performance for the tour, it obviously ran during the season but you’re joining the production at this point, aren’t you?

Yes. In the festival, I was performing the role of Morgana in new production of Alcina, so I’ve been at Glyndebourne for many months, but I’m fortunate that I’m now on the tour with this.

You’ve played the part before, with Seattle and Welsh National Opera, but how did you come by it for Glyndebourne?

I stepped in for the last performance of The Rake’s Progress last year for Nadus Williams – who’s playing the Countess on tour with me in Figaro – as she couldn’t do the last day due to scheduling issues and Covid, and that began our relationship.

So, this was your first full season with Glyndebourne?

Yes, and I’m delighted. Not only do they treat their artists brilliantly, but their productions are outstanding. It’s no wonder they’re internationally renowned. And I just love the role. She’s my favourite character in opera; she’s very real, three-dimensional and I feel like I share a lot of characteristics with her.

So, Susanna’s definitely a favourite. Are there other roles that stand out for you?

Yes, too many! I played Cleopatra in Handel’s Guilio Cesare with the English Touring Opera a few years ago quite early in my career, and I absolutely loved that role. I love singing Handel. This summer singing Morgana in Glyndebourne’s first ever production of Alcina – and their Handel productions are famous – so being able to create that role was terrific. She’s got the main aria in the piece, and there’s a dance number – I have a background in dance – so I really enjoyed bringing a lot to that role. And one of my absolute favourites was singing Gilda in Rigoletto for Seattle. I love Verdi, and Gilda’s role is stunning; it’s emotional, it’s dramatic. It’s not remotely easy to sing but it’s really rewarding.

Benjamin Williamson as Tolomeo and Soraya Mafi as Cleopatra in English Touring Opera’s ‘Giulio Cesare’ (Photo: Richard Hubert Smith)

Are there any parts you’d wish to play, or companies you’d like to sing with?

I would love, absolutely love, to sing Lucia di Lammermor, which is a fabulous coloratura role. Another dream role is Sophie in Der Rosenkavalier, which I’ll be singing next year for the first time. Ideally, you want to go to the directors you’re interested in working with, really; I love the work of Barry Kosky, who was at the Komische Oper for a long time, and the conductor John Wilson and his work with operetta and musical theatre, and I’ve already worked with Carlo Rizzi, on my first production of Figaro when I sang Susanna with Welsh National Opera. Working with him on my first time singing the role was an absolute luxury, he gave me so much confidence to go on to other companies. He’s passionate about conducting for singers and getting the drama.

In terms of the relationship between performer, director and conductor, is there anything that you’ve added to the role that’s been the result of that working relationship?

Oh, my gosh, of course. That first time, I came quite rough-and-ready to the role. And Carlo, being a native Italian speaker, really helped with the recitatives. He never told me how to do it, he simply told me “Make it convincing to me”. We work with Italian dialect coaches, of course, but when he said ‘just convince me’, that gave me the confidence to make my own choices.

Different directors want to highlight different themes, and different productions require a different treatment of the role. Susanna has same basic core values; she has a strong moral compass, she obviously loves Figaro, and is loyal to the Countess, but she’s also very playful and quick-witted, always three steps ahead of everybody else – but this is my first production that isn’t strictly period, and that brings different interpretations.

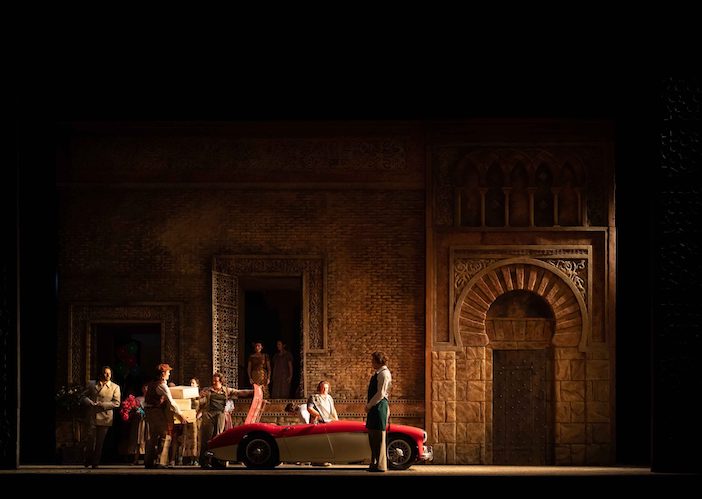

Marcellina (Madeleine Shaw), Bartolo (Henry Waddington), Don Curzio (Stephen Mills), Count Almaviva (George Humphreys), Susanna (Soraya Mafi) and Figaro (Alexander Miminoshvili). © Glyndebourne Productions Ltd. Photo by Richard Hubert Smith.

Grandage’s production is set in southern Spain in the ‘60s, at the end of the Franco era, so here she’s much more conservative, there’s a wariness or nervousness about their wedding night, for example, there’s more innocence. But, in Seattle, it was a different setting entirely, she’d have probably rolled around in the haystack a few times, so we had to be far more tactile. And all of those nuances inform how you use the text, how you colour your voice, and how you conduct your relationships with the other characters on stage.

So, it’s as much the acting performance as it is the singing…

Oh, absolutely. They have to work together.

You mentioned that you have a background in dance, you were originally destined for a career in the ballet, weren’t you?

I love dance, all forms, and trained in ballet, tap and modern dance. I had issues with injury, though, particularly my back during a production of The Nutcracker, but that aside, I found competition in dance quite stressful, whereas with singing I never found that, it’s more like a release. I find it’s more beneficial being an opera singer who can dance, than a dancer who does a bit of singing, and directors now are keen to use artists who are not just about the voice but want to improve their acting and exhibit other skills. Opera as an industry has always embraced other art forms, and directors are being more and more inventive as to how they use their singers – but not, obviously, to the detriment of the singing.

Indeed, it should add to it but not overpower it…?

Exactly. It has to make sense within the character and the production.

Rehearsing Susanna for Glyndebourne’s tour

You’ve had a very extensive and varied repertoire, even at this still early stage in your career; how do you balance the heavy, dramatic works of, say, Britten, with the lighter, more comedic Donizetti, for example?

It’s how you project. Even in Britten there are many voice types, whether heavy, light, lyrical, within a particular range, it’s all about the technique for projecting. And great conductors know how to balance an orchestra with a voice – and theatres, too, the acoustics need to be taken into account.

Do you have a preference for the type of role, the more dramatic or comedic…?

Honestly, I like the variety. That’s also why I like working as a guest artist, because I get to go to new places, work with new creative teams, and why I don’t necessarily join a company. I get itchy feet. It also means vocally you have to be aware of what’s going on – it’s easy to become unstuck if you’re going from singing Verdi to singing Britten to Mozart if your technique’s not solid, or you’re taking too much work on.

So, there’s a logistical challenge to managing your voice?

Yes, you look at your diary and think ‘how’s that going to work?’ plus keeping in touch with your vocal tutor, and listening to people who give honest feedback. It’s about constant learning and maintaining your instrument.

The Marriage of Figaro (dir. Michael Grandage) at Glyndebourne Opera

This being the 10th anniversary of Grandage’s production, what is it d’you think that makes Figaro so enduring?

I think it’s the characters, they’re so human. It’s very funny, and there’s genuine love on stage; you just fall for Figaro and Susanna, you want to be on their team. And, d’you know, the music is just fantastic. There’s not a moment where you think you have to sit through to get to the good stuff, every single moment is glorious. And on top of that, right now, it’s nice to have a laugh.

Very true. And as you’re about to embark on the tour, what are you looking forward to about that?

Just that, the fact that this is going on tour, going to various venues. And, for me particularly, that it goes to the north. I’m from Manchester, and was introduced to opera by Opera North and the outreach that they do, and with Glyndebourne’s outreach, and that is so important. Opera is wonderful, I love opera, I believe in opera, but for opera to be sustainable young people need to have access to it and need to know what it’s about before any preconceptions come into it. Something I do is to go into primary schools in the northwest and I sing and we talk about what opera is; and for them it’s simply music, it’s singing, it’s relatable. That outreach is really important.

The cast of Glyndebourne’s Marriage of Figaro tour in rehearsal

Indeed. You think of Glyndebourne, you think of the Royal Opera House, and people think it’s a bit elitist and out of reach, but its origins are the opposite, it began as an entertainment form for everybody…

Yes, exactly, and for people working on this, putting this on, we’re from all different backgrounds, different countries, different socio-economic backgrounds. What unites us is music, we love music and telling stories, and that’s the key, getting it out to young people and telling them it’s for them.

Soraya, thank you, it’s been an absolute pleasure chatting to you. Best of luck with the run, and the tour, and I can’t wait to see it!

Thank you, it’s been lovely chatting to you.

Michael Grandage’s Marriage of Figaro runs at Glyndbourne from 8th October 2022 before embarking on a nationwide tour through to November. The Glyndebourne Tour takes place at Glyndebourne from 8 – 29 October and then at Milton Keynes Theatre (1 – 5 November), The Marlowe, Canterbury (8 – 12 November), Norwich Theatre Royal (15 – 19 November) and Liverpool Empire (24 – 26 November). Visit www.glyndebourne.com/tour for more information.

For more information about Soraya Mafi, including career highlights and future performances, please visit www.sorayamafi.co.uk.

Header image: Soraya Mafi as Cleopatra in Giulio Cesare (ETO), Photo by Richard Hubert Smith