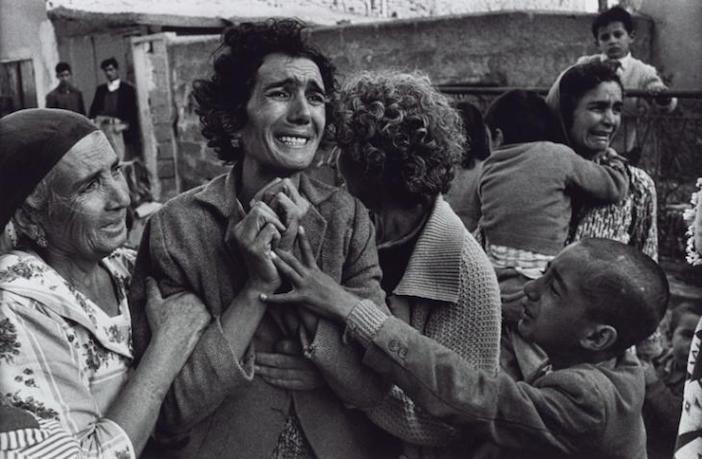

If you’re not familiar with Sir Don McCullin’s name, as the UK’s leading war photographer you’ll almost certainly recognise his photographs. From the anonymous Shell-Shocked US Marine, Vietnam 1968 to the British soldiers charging in Londonderry, Northern Ireland 1971, Germans peering over a nascent Berlin Wall or the family deep in mourning in Cyprus 1964, his images are seared into the public conscience and have become symbolic of conflicts around the world.

Shell-shocked US Marine, 1968 © Don McCullin

In a rare retrospective, Tate Britain is exhibiting more than 250 of McCullin’s photographs, each printed by the 83-year-old in his darkroom. Spanning a lifetime of work, the exhibition reveals the scope of his photography – from his images of war-torn countries through to disenfranchised communities in England and abroad, as well as landscapes, still lifes and travel photography. And then there’s his most recent project, ‘Southern Frontiers’, which connects conflict and landscape as he documents the physical remains of the Roman Empire in north Africa and the Levant – including monuments demolished in Syria by the so-called Islamic State.

That McCullin has become so renowned for his conflict photography is partly due to his long relationship with the Sunday Times Magazine, which published many of his assignments. Yet he dislikes being known as a war photographer and struggles to reconcile the complexities of a career that involved documenting others’ suffering. He is, however, unquestioning about the importance of these images, telling us: “You have to bear witness. You cannot look away.” Be aware, however, that parts of this exhibition are difficult to see.

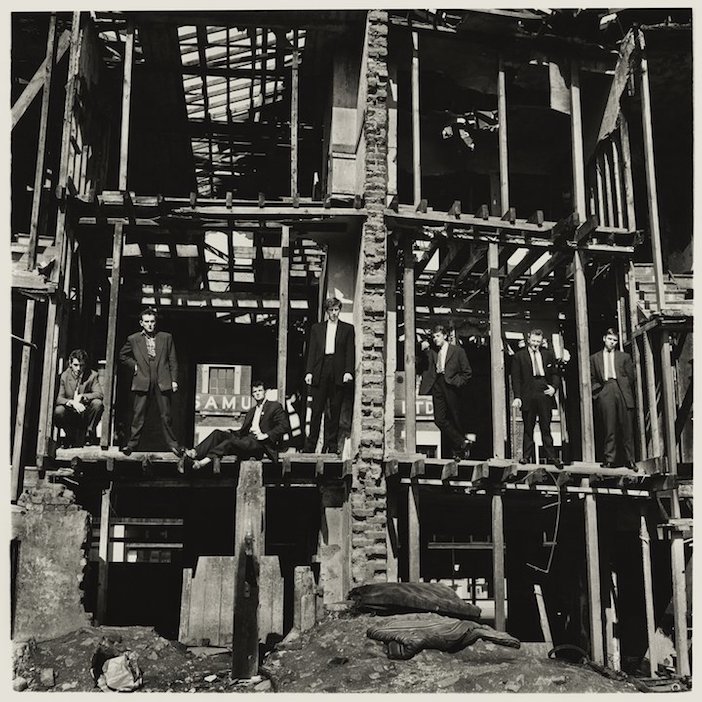

McCullin’s career started by chance after members of a gang he went to school with in north London were accused of a policeman’s murder. A photograph he had taken of The Guv’nors in their Sunday suits, posing menacingly in the bombed out structure of a building, catapulted him to fame and he spent the next few decades documenting conflicts in Germany, Cyprus, Vietnam, Lebanon, Iran, Northern Ireland, the Republic of Congo – where he had to disguise himself as a mercenary, and Cambodia – where he was seriously injured by a mortar shell.

The Guvnors in their Sunday Suits, Finsbury Park 1958 © Don McCullin

But it was the experience of war in Biafra that taught the photographer from a tough childhood in Finsbury Park compassion. His images of Biafra’s starving children in 1968 are no less horrifying with the passage of time and he has spoken of the traumas he still struggles with – particularly the memory of leaving an emaciated albino boy, days from death, who had silently approached him and held his hand. It is difficult to describe the impact of seeing this child’s photograph, and those of the other children and adults who were to die of starvation there. But McCullin is rightly adamant that these images must have a life beyond his archive: “We cannot, must not be allowed to forget the appalling things we are all capable of doing to our fellow human beings.”

Poignantly, one of the most striking aspects of this exhibition is its universality. It spans different decades, different continents and different subjects, yet these images are as prescient now as they were 50 years ago. And, at 83, he hasn’t given up trying to share his message of the futility of war. His black and white photographs are unflinching but taken with compassion and empathy, and their heightened contrast amplifies their impact. McCullin is meticulous in his printing process, striving to do justice to those he feels he has a responsibility to speak for.

Cyprus 1964 © Don McCullin

This is a complex, challenging and unforgettable exhibition that’s been sensitively curated to address questions that arise from both taking and sharing images that show some of the worst of humanity. The accompanying literature is reflective and absorbing, and gives voice to McCullin’s thoughts on matters such as responsibility and consent. He previously said of his approach to photographing people: “I tried to let their eyes meet my eyes…I want them to see that I’m looking at them through a pair of eyes that have enormous compassion and understanding.”

The importance of this connection resonates in his work documenting homeless people in London’s East End in the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, where he spent time getting to know those he photographed and depicted them subjectively. There’s a closely cropped photo showing the interlinked, worn fingers of a woman named Jean; the penetrating stare of a homeless Irishman whose dignified eyes speak volumes in a scarred face; and the foetal pose of another homeless man asleep on the pavement, his ragged body resembling the corpses of McCullin’s war photographs.

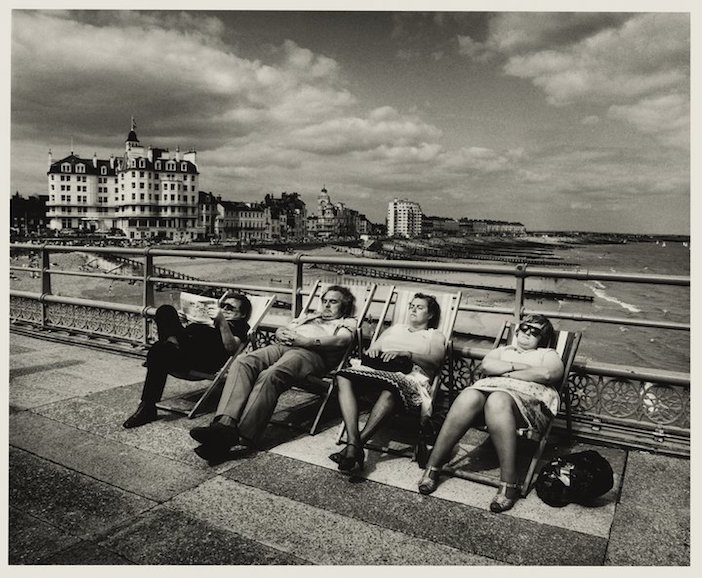

But there are also moments of joy and humour in this exhibition – the six young boys sitting on the stone book of a huge statue in Kurdistan, children playing outside Buckingham palace, knobby knee contests in Southend-on-Sea and images of a bygone era in 1950s London where sheep are driven through a foggy dawn and horse-drawn carts deliver beer.

Seaside Pier on the South Coast, Eastbourne 1970s © Don McCullin

His extraordinary photographic skill is particularly striking in his Weston-esque still lifes, his atmospheric photographs of Scottish glens and his mesmerising images of the crumbs of Roman Empire in Syria – architecture built and destroyed by war, where long shadows stretch across the landscape as though echoes from history.

In a time that feels inundated with vacuous images, McCullin’s retrospective is a stark reminder of the power of photography. There are many exhibitions that offer up easy enjoyment with little real impact but this isn’t one of them, and the Tate should be commended for stepping outside that mould; this is a rare and moving exhibition. McCullin once said, “When it comes to images related to war, I don’t give you a free ride.” And why should he?

Don McCullin ran at the Tate Britain from 5th February to 6th May 2019. For more information, visit www.tate.org.uk.