When I first heard the term ‘plant hunter’, I have to admit to being puzzled. Surely hunting involved chasing down something that did not want to be caught? How could one ‘hunt’ a plant, an organism that is literally rooted to the ground? Finding myself picturing a man in a pith helmet sneaking up on a geranium, I was sufficiently intrigued to want to find out more.

I soon learnt that the ‘hunting’ part of plant hunting was a reference to the dangerous search for rare plants in remote and often inhospitable places. As a result, plant hunters could often find their lives every bit as at risk as hunters of big game.

David Douglas (image courtesy of Wikipedia)

The period of greatest demand for British plant hunters was undoubtedly the 19th century. The more the Victorians saw of the delights the Empire had to offer, the more they became obsessed with exotic plants. To satisfy this craving, botanic gardens and commercial nurseries began recruiting people they could send abroad to increase their collections; individuals who combined the skill of a botanist with the intrepid spirit of the explorer.

I read of David Douglas – of Douglas-fir fame – who in 1834 was gored to death by an angry bullock, after falling into a cattle pit in Hawaii while looking for screw-pine trees. Of Robert Fortune, who battled pirates off the coast of China in order to protect a consignment of camellias and hydrangeas. Of Ernest Wilson, who broke his leg in two places after being caught in a landslide while collecting lily bulbs in the Min Valley in China. Of George Forrest, who spent nine days on the run when his search for rhododendrons was interrupted by a band of murderous Tibetan lamas, hellbent on cutting out his heart.

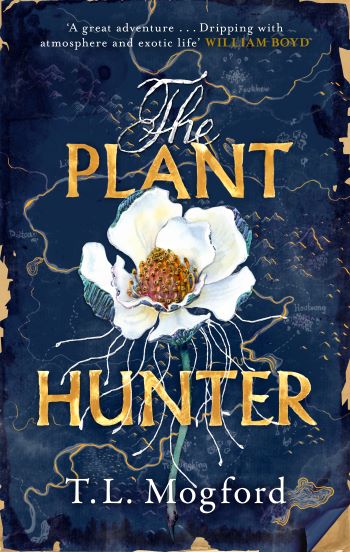

These tales proved so compelling that I decided to create a fictional plant hunter of my own, and write a novel about his adventures. But it was only after The Plant Hunter was published this February that a friend was moved to enquire whether I knew of any modern-day plant hunters, whose travails might match those of the Victorians. I didn’t, so my friend helpfully lent me a book called The Cloud Garden, and told me to get reading.

These tales proved so compelling that I decided to create a fictional plant hunter of my own, and write a novel about his adventures. But it was only after The Plant Hunter was published this February that a friend was moved to enquire whether I knew of any modern-day plant hunters, whose travails might match those of the Victorians. I didn’t, so my friend helpfully lent me a book called The Cloud Garden, and told me to get reading.

The Cloud Garden is a gripping memoir written by two young men who were kidnapped by Colombian guerrillas while exploring an area known as the Darien Gap in March 2000. One of the authors is Paul Winder, an inveterate backpacker who was keen to test himself by trekking through one the most dangerous corners of the world. The other is Tom Hart Dyke, an amateur botanist who was on the hunt for the beautiful and undiscovered orchids he felt sure must be found in the region.

After their release by their captors in December 2000, Winder settled down to married life in England, but Hart Dyke found himself bitten by the plant-hunting bug. In 2002, this time accompanied by a Channel 4 film crew, he set off for West Papua in search of more rare plants, then continued travelling the globe on his own, working with local conservationists to amass an enormous seed collection, which he has since put to good use by creating a botanical paradise in Kent known as the World Garden.

I was so taken by Tom Hart Dyke’s story that I emailed his agent, asking if we might meet. To my surprise, Tom agreed, so I jumped in the car and headed south to Kent.

The World Garden is situated in the grounds of the Hart Dyke family seat, Lullingstone Castle. Tom emerges from his home, the castle’s Tudor gatehouse, to greet me. Though a little older-looking than in the photo on the front of his book (aren’t we all?), he exudes the same enthusiasm and ebullience he shows in his writing.

We pass beneath the redbrick archway of the gatehouse into the grounds of the castle, and I remind him of the section of his book where he describes how he overcame the daily stress of life in captivity: ‘I filled days dreaming about my ideal garden. Each day it became more vivid in my mind, more detailed and crammed with every plant I had ever loved…’ Is the World Garden the realisation of that dream, I ask?

‘When I was writing the book,’ Tom replies, ‘I went back to the diary I’d kept while we were kidnapped, and was reminded of my fantasy garden. I’d sort of forgotten about it, but then I thought, ‘Why not make it happen?’’

Close to the main house – where Tom grew up, and his mother still lives – is a beautiful, flint-faced chapel named St Botolph’s. ‘That’s where my memorial service was going to be held,’ Tom explains. ‘Most of my family had given me up for dead. But then, just before Christmas, we suddenly emerged from the jungle.’ He smiles. ‘No one could quite believe it.’

A green parakeet flits overhead, a descendent of one of the feral birds that first appeared in South London in the 1970s, and have now migrated to Kent. ‘We were forced to eat things like that in captivity,’ Tom observes. ‘Armadillos and monkeys, too.’

I ask him if he has nightmares about his time in Colombia, and he tells me that writing the memoir, and creating the garden, have proved cathartic. But then he pauses and shows me the scars on his legs, where he had to squeeze out parasitic worms from beneath his skin, a stark reminder of what must have been a terrifying ordeal.

We continue to the entrance of the garden. Outside, a placard shows pictures of famous plant hunters of the past – I recognise David Douglas and George Forrest amongst their number – and reveals where certain of their introductions grow within the garden. Astonishingly, though, I learn that most of the 6500 species here were collected by Tom himself. Does he see himself as following in the footsteps of the great Victorian plant hunters?

Tom dismisses the comparison, but eventually concedes, ‘I suppose I’m a mini, mini version.’

We begin our tour in the Hot and Spikey House, full of towering cacti and prehistoric-looking bromeliads, before moving to the Orchid House, where Tom spots a rare species he collected from Tasmania flowering for the first time. A significant number of plants in the garden remain unnamed, Tom tells me, and hearing him describe how he collected their seeds, and succeeded in germinating them, is an incredible privilege.

We find ourselves in the Cloud Garden, a temperate house that shares the same name as Tom’s book, and contains species found in elevated jungle regions similar to where he was held hostage. I ask him if he has ever been back to Colombia, and he replies that he once got as far as the Ecuador-Colombia border, then found himself overcome by ‘an urgent trembling’, and had to turn back.

The scars may still be raw, but the World Garden stands as a powerful testament to Tom and Paul’s survival instincts, and a lasting memorial to the beauty and diversity of the planet we all share.

The World Garden opens for the 2022 season at Lullingstone Castle on 1st April. For more information, including details of events, please visit www.lullingstonecastle.co.uk. ‘The Plant Hunter’ is published by Welbeck and is available in hardback in all good bookshops.