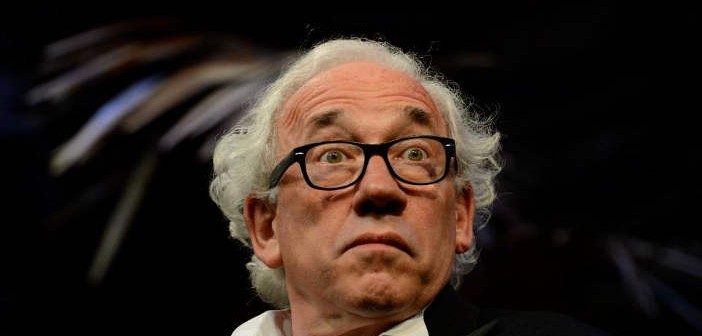

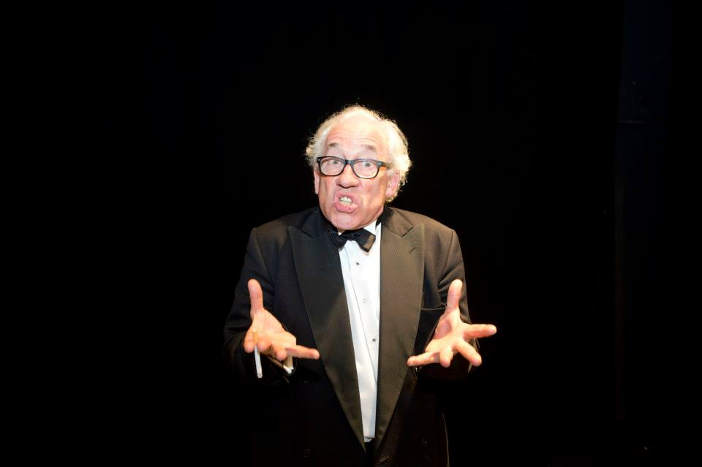

Simon Callow peeks his head around the side of the stage, whisky glass in hand and a cheeky purse troubling his lips. Trussed up in black tie and his most ostensibly intellectual dark-rimmed glasses, he surveys the audience with mild bafflement. After a benevolent raise of the eyebrows, he seems to decide that we’re a decent enough looking bunch and on he plods, microphone in-hand.

The words subsequently fired out of his mouth are startling not just in their coarseness, but in the eerie knowledge that they were written a double millennia ago whilst sitting ever so comfortably here, in the 21st Century. Is he reading the right script? Ok, so he’s coming across as a rather belligerent, small-minded and bitter old man but it’s not like I haven’t heard worse on the bus. So is this a deliberately truculent form of after-dinner speech? Perhaps I should start heckling. Actually, no – I don’t think that’s the vibe here. I mean, he just walked on and disgorged a torrent of vitriol – misogynistic, homophobic and deeply snobbish wrath. What in God’s name is his problem? This guy must be the most determined misanthrope that ever lived. He might hail from the 2nd Century, but even Frankie Boyle couldn’t steal that title from him.

When Callow first performed Juvenalia at The Bush Theatre in 1976, a common observation of this highly successful production was its relevance to modern life and its concerns. Now, Peter Green’s remarkably astute translation from the Latin of Juvenal’s Sixteen Satires has once again been reworked for the stage, this time directed by Simon Stokes. It transferred to the St. James Theatre after showing at this year’s Edinburgh Festival.

Ever the academic, Callow takes a keen interest in the historical context of this work. Anyone who witnessed his one-man biographical works on Shakespeare and Wagner will know his deep passion for getting into the minds of his subjects, and just because he has not written this monologue does not lessen his fervour. A poet born circa A.D. 55, Juvenal spanned philosophy, politics and current affairs with unstinting wit, and acerbity. Callow calls him “one of the most vicious satirists of yesteryear,” on account of the “cartoon-like imagination” that allowed Juvenal to taunt the public figures and main opinions of the day. Think Private Eye for Roman times.

And that brings us to the main gripe that you’ll hear about this work: that it’s not very nice. Granted, it snipes at everyone and everything, assuming that women are all “sex-mad” schemers, that gay marriage is unfathomable, that marriage is an unmitigated mistake in every situation. It talks crudely of eunuchs and questionably of young male lovers, and I can’t tell you what else, often in language languishing in the sorry depths of depravity. But perhaps we just don’t know how to take a joke these days, suggests Callow. “We’re all a lot more delicate now,” he says. “There’s a tremendous amount of anxiety about offending anybody.” So why not have some fun?

Amongst the vulgarity, Juvenal does actually touch on scholarly subjects, including reason, rationality, wealth, respect, the gods, fidelity and mortality. Despite delivering a vast amount of his speech with a Rex Harrison-esque growl (watch ‘Why Can’t The English Learn To Speak’ from My Fair Lady, for reference), Callow is able to end on a more reflective note, as Juvenal attempts a parting moral aphorism. It’s not seamless, and it can be difficult to keep up with the text, which can be long-winded to the point of waffling, but it’s worth it to see Callow tottering about the stage with an ever-depleting bottle of Famous Grouse tucked into his pocket. And why the modern dress, Mr. Callow? “It would have been ludicrous in a toga, frankly.”

Juvenalia at the St James Theatre. For more information on future productions visit the website.