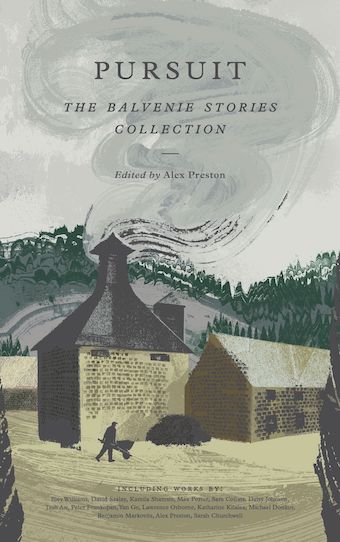

It’s no secret we’re big whisky fans here at the Arb, and we like to run a story or two. So when single malt maestros Balvenie celebrated their new ‘Stories’ expressions with a beautiful collection of tales from leading authors from around the world, it seemed like a match made in heaven.

Called Pursuit, it’s so-named for the inspiration given to each of the authors for their entry. Here, in an extract from ‘Endurance: One Hundred Years and One Day Later’, Kamila Shamsie ventures to Antarctica, in the footsteps of one Ernest Shackleton…

Soon after we boarded the Russian icebreaker, Polar Pioneer, in Ushuaia, we were directed to meet at The Mustard Point. Surely the colour not the condiment, I thought, walking down the ship’s corridors, which were unpromisingly lined with sick bags. Once outside I saw the rest of the passengers gathering next to hulking bullet-shaped objects that were clearly orange. No, not gathering – mustering.

The giant bullets were submersible lifeboats. In we climbed. Pressed together on benches, we listened to the expedition leader explain all the ways in which this vessel would keep us alive and safe if the Polar Pioneer, which was to be our home for the next ten days, ran into trouble and we were forced to leave. It’s just as well I didn’t know then that Shackleton’s Endurance had set sail from South Georgia to Antarctica exactly one hundred years and one day ago, on 5 December 1914, and two days later first encountered the pack ice that would ultimately crush her.  There were two lifeboats on the Polar Pioneer and about sixty of us divided between them. The word ‘sardines’ was the only one that would do – and that was before we were told that in the event of an actual evacuation the crew would join us, which would add another dozen or so people to each vessel. Then we were shown the bucket that would have to serve as ‘the facilities’ for the hours or days we were confined to the lifeboats. It was so awful to contemplate we passengers couldn’t even hazard eye contact, let alone a joke.

There were two lifeboats on the Polar Pioneer and about sixty of us divided between them. The word ‘sardines’ was the only one that would do – and that was before we were told that in the event of an actual evacuation the crew would join us, which would add another dozen or so people to each vessel. Then we were shown the bucket that would have to serve as ‘the facilities’ for the hours or days we were confined to the lifeboats. It was so awful to contemplate we passengers couldn’t even hazard eye contact, let alone a joke.

Back out in the open, we watched South America recede; in time, the image of the bucket receded too. Ahead lay Antarctica – a word I had always vaguely associated with foolhardy men doing unnecessarily dangerous things that drove them to kill sled dogs, and sometimes eat them, in order to stay alive. I had never had a longing to go to the frozen wastelands of the earth – and yet when I was asked to do just that for a travel piece, something in my heart started singing. Who can understand the ways in which even the most urban among us can feel a pull towards the absolute unknown?

But when they tell you ‘Antarctica’ they skip over the ‘Drake Passage’ – a body of water that is the meeting point of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and the Southern Seas, made more remarkable by the fact that there is no significant landmass anywhere along its latitudes. No landmass means nothing to provide resistance to currents as they travel and grow in strength around the globe. What results are the world’s choppiest seas. Or put in more visual terms: your view out of the porthole of the room in which you’re lying prone on your bed is sky, sea, sky, sea. I don’t mean a mix of sea and sky. I mean at one moment you are looking at nothing but sky and the next the porthole is covered with water. Repeat for thirty-six hours. The most surprising part of all this was how perfectly right it felt to be horizontal. Vertical was all wrong, but horizontal was fine, almost soothing. Stay horizontal, take seasickness pills, sleep, sleep some more.

Later, I understood the narrative necessity of the Drake Crossing. It wouldn’t have been right to progress undramatically from Argentina to Antarctica on calm seas – the tempest-tossed voyage with its drug-induced drowsiness was an essential way of marking the passage from one world to another.

Because Antarctica really was another world. One pared down, pared back. There was sea and sky and icebergs and rocks. There were penguins and seals and petrels and skuas and occasionally whales. There were my fellow travellers and the ship’s crew and the expedition staff. There was the Polar Pioneer and the inflatable Zodiacs. There was the morning expedition and the afternoon expedition. There was breakfast, lunch and dinner. There was sleep. There was landing on the continent and there was cruising between the icebergs. There was endless blue and endless white. There were layers and layers of clothes to put on and take off. There was my copy of Moby Dick. There was watching. There was talking, too, but most of it was about the day’s watching – did you see the calving of the iceberg, the fluke of the whale, the line-up of gentoo and chinstrap and Adélie penguins, the blood-smeared slab of ice?

It was astonishing how quickly the world disappeared, how much I revelled in its disappearance. I too became pared down in what I was willing to absorb and with what I was willing to interact. Antarctica, Moby Dick and the people on the ship – that was as much as I could bear of the world. As early as day two, I wrote this in my journal: ‘A note in the folder on the door tells me a complimentary email account has been set up for me. I can’t imagine using it.’ I never discovered how or where this email account was supposed to work on a ship – indeed, on a continent – where my smartphone only functioned as a camera.

It was astonishing how quickly the world disappeared, how much I revelled in its disappearance. I too became pared down in what I was willing to absorb and with what I was willing to interact. Antarctica, Moby Dick and the people on the ship – that was as much as I could bear of the world. As early as day two, I wrote this in my journal: ‘A note in the folder on the door tells me a complimentary email account has been set up for me. I can’t imagine using it.’ I never discovered how or where this email account was supposed to work on a ship – indeed, on a continent – where my smartphone only functioned as a camera.

A couple of days later one of the passengers asked another a question and received the reply, ‘I don’t know, and I love that we can’t google it.’ Yes, exactly, I found myself thinking. There was a strange pleasure in returning to a state where so many things could be unknown. Tiny bits of trivia, the name of an actress, a quote from a book, the weather in some other part of the world, the causes of seasickness. The brain asked a question, cast about for an answer, realised, no, I don’t know that and neither does anyone else standing around me – and there the matter rested. It was, I discovered, almost always fine not to have the answers to the questions that came and went from my mind; and on those occasions when it wasn’t fine there was something so gloriously human in the wondering and wondering – what is the answer? How do I find it? How little I know.

See how Kamila’s Antartic adventure concludes, along with 14 other stories authors including recently long-listed Booker nominee Max Porter, in ‘Pursuit’.

Balvenie ‘Stories’ are available from master of malt and all good whisky stockists. Pursuit is released on 3rd October and can be purchased from all good bookshops.