As the BBC’s landmark natural history series, A Perfect Planet, concludes on our screens this Sunday with Humans, Toby White talks to its producer-director, Nicholas Shoolingin-Jordan, about how on earth one puts these programmes together, what’s unique about this final episode, and working with the incomparable Sir David Attenborough…

Let’s start at the beginning, how did you get involved in A Perfect Planet?

I met Silverback (the production company), whose work I’d always admired having watched The Hunt, when I moved to Bristol. I had a chat with Huw (Cordey) and, funnily enough, A Perfect Planet was in its planning stages. But at that point I was approached to work on One Strange Rock for National Geographic. It was following that, that it all became quite serendipitous. I’d got back from wrapping on One Strange Rock and got a phone call from Alastair (Fothergill, Executive Producer of A Perfect Planet), which was very flattering, asking about my availability. I said ‘Actually, I’m free and looking for my next project’. So, we met and talked through some projects and he and Huw mentioned Perfect Planet. It was already going into production but, fortuitously for me, they needed a producer and asked me if I’d like to join the team to produce two of the episodes.

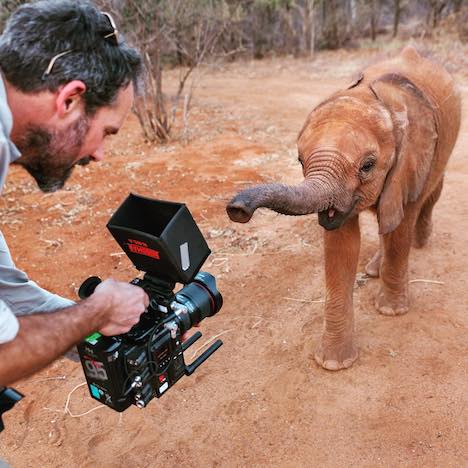

Photo by Huw Cordey (c) Silverback Films

Did you have a choice of which episodes?

When I came on board they had all but two episodes, so I didn’t really have a choice! But, usually, when you’re formulating what the programmes are going to be, often there’d be a natural fit. You’d go with specialisms, whether it’s underwater, or rainforests, for example. You can also go after the subject you found really fascinating, and certainly for this one there was a part that I was really drawn to, the Humans episode. I wanted to do something that had an impact for conservation, to help communicate the problems that we are facing with the natural world being under pressure. So Humans for me very much sealed the deal.

When you’ve decided on the series theme, how do you decide what makes up each episode, from presumably all the myriad of stories and subjects out there? How does an episode evolve?

When you have a series such as this, you’re looking for a strong narrative. The forces of our planet, and how life is shaped by them, was that narrative. We knew what those forces were at the beginning: volcanoes, sunlight, weather and ocean currents. Finding the stories to fit those forces is actually harder than you think because they’ve got to tie completely to the episode narrative. So, a huge amount of research goes in to scouring the world for the best stories. A beautiful example is Huw’s Kamchatka story where that entire ecosystem of the Kurile lake is created by that volcano. In my sunlight episode, there’s the fig wasp story-

That was incredible…

Yes, wasn’t it. It had only ever been covered once before (in a documentary called Queen of Trees) but we looked at it and realised we could go deeper. Sunlight is absolutely fundamental to the lifecycle of that story, for the wasp, the fig, the forest. That whole system could only ever happen on the equator, with its regular 12-hour day.

Presumably you don’t want to be repeating what’s already been done, you’re also trying to find a unique story…

Exactly, and I think the audience demands more now. It’s not enough just to show a beautiful natural history sequence, it has to have a strong narrative that drives the film and cements it together. I think, hope, we’ve managed to do that here, and in a way that we appreciate the planet more, and how everything is connected.

So, we looked at a lot of natural history stories and most of them didn’t work, for one reason or another, so we had to either find new ones or understand how these planetary forces impacted those stories, which meant finding new angles. The silver ants in the Sahara, for example, had been filmed before, but not in this context. We very much did it through the lens of ‘these are the greatest solar predators on the planet’, they are masters of this extreme solar landscape.

It’s that narrative element that makes it compelling. That ants sequence, I was on the edge of my seat watching that, ‘will they get back in time?’

And we nearly didn’t get it. You’re basically trying to film the tiniest creature in the hottest place on the planet. We were working with scientists who’d been studying these ants in Morocco, but when we arrived on location there were no ants where they said they were going to be. So, firstly, we had to find them, trudging over dunes in searing heat, until eventually we found some nests. The trouble then was we kept losing them because among desert dunes everything looks the same, so we marked them out with little poles with flags so we could remember where the nest was the next day.

But the biggest problem was the heat. I got a thermometer out of the medical kit and it shot to 40 in a second. On the sand it was pushing 60 degrees, you’d scald your hand if you touched it, and with our cameras that close to the sand they just wouldn’t work. So, we sent a message back to Silverback HQ asking for ideas and various elaborate suggestions came back involving tinfoil and reflectors but everything we tried was too impractical, largely because of the wind.

Then we started thinking of latent heat and evaporation, going back to school science, and that desert wind turned out to be our saviour. Our fixer appeared one morning with long sheets of white cotton they normally use as turbans, which we soaked in water, wrung out and then wrapped around the camera. Unbelievably, the camera cooled significantly, and we could operate. We also wrapped the cameraman in one, too, much to his relief.

Necessity being the mother of invention. Brilliant. You film quite a bit of it yourself, don’t you…

I do like to, yes. I don’t do the long lens work but I do like to get involved, particularly with different kit. When we shot the garter snakes in Canada, I shot quite a bit of that. We used an amazing crane to do the moves past the snakes – that’s my camera work. And for the Humans episode, I shot a lot of the material, the turtles, the elephants. I’m not a natural history cameraman – and certainly not one that can endure sitting in a hide for six months – but I tend to do the drone shots or scenics, or some of the more specialist work using various gizmos. I enjoy the camerawork because it’s so creative. What’s key is that as a director, there are no degrees of separation then. You’re shooting what you want to shoot and how you want to shoot it.

I do like to, yes. I don’t do the long lens work but I do like to get involved, particularly with different kit. When we shot the garter snakes in Canada, I shot quite a bit of that. We used an amazing crane to do the moves past the snakes – that’s my camera work. And for the Humans episode, I shot a lot of the material, the turtles, the elephants. I’m not a natural history cameraman – and certainly not one that can endure sitting in a hide for six months – but I tend to do the drone shots or scenics, or some of the more specialist work using various gizmos. I enjoy the camerawork because it’s so creative. What’s key is that as a director, there are no degrees of separation then. You’re shooting what you want to shoot and how you want to shoot it.

We’ve come to expect sweeping, stunning visuals in natural history programmes now, but at the other end of the spectrum, it’s the macro work that really makes it compelling. I’m thinking of that fig wasps sequence you mentioned, how do you go about capturing that?

We went to Thailand where we worked in a botanic garden on the edge of one of the national parks that has these fig trees, and we created a field studio with a mini ‘set’ – obviously you can’t be up a tree with a rig to get those sequences. So, you’re on location, filming it as authentically as you can, but you have to bring things down to a level where you can operate – and, importantly, where you can have lighting because for macro, you need light.

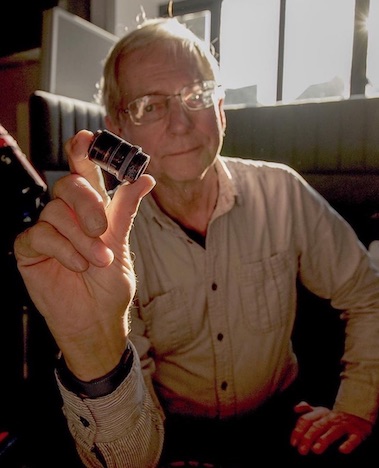

The other thing you need is a guy called Alastair MacEwen, who has filmed pretty much every stand-out macro sequence you’ve ever seen. When we arrived in Thailand and we saw these fig wasps, they’re not like a wasp you’d recognise, they’re tiny-

How big?

Smaller than a fruit fly, about 2mm long. The tip of a ballpoint pen. So, when we first saw them, we really wondered whether we were going to be able to do it at all. But Alastair is the master of macro. He has his box of lenses with him, that he’s carried with him for 30 or 40 years, and he pulled out his normal lenses and they weren’t enough, so he rummaged in his box of tricks and produced these tiny microscope lenses, really high precision Zeiss lenses which he’d never used. He attached them to the camera, with the extension tubes, it reached the magnification we needed and it was pin sharp. So, you’re basically filming a macro sequence with a microscope lens.

Smaller than a fruit fly, about 2mm long. The tip of a ballpoint pen. So, when we first saw them, we really wondered whether we were going to be able to do it at all. But Alastair is the master of macro. He has his box of lenses with him, that he’s carried with him for 30 or 40 years, and he pulled out his normal lenses and they weren’t enough, so he rummaged in his box of tricks and produced these tiny microscope lenses, really high precision Zeiss lenses which he’d never used. He attached them to the camera, with the extension tubes, it reached the magnification we needed and it was pin sharp. So, you’re basically filming a macro sequence with a microscope lens.

You’ve obviously got to capture the sequence in real time, so how long did that take to shoot? Were you poring over your monitor for days waiting for something to happen?

It took about three weeks, but we had a lot of different figs at different stages so we could get inside the fig at just the time we needed.

So, you know what you want to capture, but you are at the mercy of nature…

Yes, you have a shot list of key bits you want in the story; tunnelling in, the collecting of the pollen, the males hatching, then mating with their ‘sisters’ – which is really hard to film because you can’t see it with the naked eye – then we had to get them emerging, and don’t know quite when that’s going to happen so we were poised, watching them, waiting to get into position.

That’s why it takes time, but that’s why I love macro sequences. One thing Huw said to me, ‘it doesn’t matter if it’s a small creature because when it’s on screen it still fills the frame’. Macro sequences can be as powerful, if not more powerful, as large animals.

Absolutely. Some of the extraordinary things that go on at the level, it’s almost otherworldly. So, putting that story together, you know what happens from a scientific or zoological level, but to create that narrative, how do you script that? And at what point does Sir David Attenborough get involved? Because he very much lends his own voice to it, so to speak…

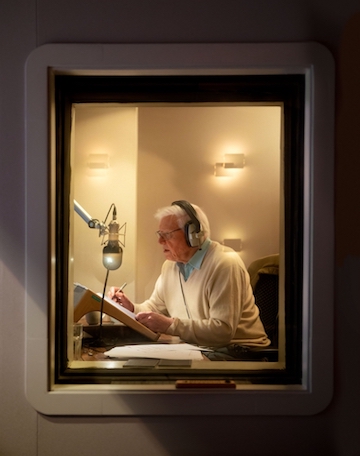

Yes, before you go and film, you know the narrative, the natural sequences of events, so you have a structure and an outline of a script too, which will evolve in the edit. The script then goes out to David, and he reads it through in detail and comes back with his suggestions. It’s a very organic process with David.

Does he lend his expertise to it?

Sir David Attenborough in the studio recording (Photo by Huw Cordey/Silverback Films 2020)

Yes, his knowledge, his attention to detail, and his passion, to get it to connect with the audience is incomparable. By the time he’s finished going through it, it feels like a great collaboration but, more importantly, it feels like it has David’s stamp on it. He doesn’t say things how I write them, he says them how David Attenborough says them. That for me was an absolute privilege to be able to have that back and forth with him over the phone.

As a naturalist, he must know a lot of these stories himself? Did he ever correct you, so to speak?

Haha. No, he never said, ‘oh, you’ve got this wrong’ [laughs]No, fortunately, and the research team at Silverback have nailed it while we’re putting the project together. We’re also working a lot with world experts in their field. But David does know all the stories. There’s never anything where he goes, ‘oh, I didn’t know that’. He’s come across it before, but it’s more his appreciation to understand the bigger picture and how it all works together. Significantly, though, he brings turns of phrase to the script that you wouldn’t have thought of, and that’s what makes these programmes what they are.

Much of why these are so compelling too, is the music, adding the emotive element and heightening the drama. Do you create the drama first and then add the music, or do you rework the edit to suit particular tension or emotion in the music?

Ilan Eshkeri, composer of A Perfect Planet

You want to get the film to the composer as early as possible, even before you have the locked picture, because you want to start getting the moods together. From that, they’ll start to write themes. Then, once you have the locked picture, he’ll fine tune the score to the picture and send over his first draft. Then it becomes very collaborative. I can ask for more impact on a particular shot, for example, and I would send Ilan (Eshkeri) furious notes after every cue came through, and we would chat them through. The great thing about Ilan is he’s such a well-established composer; he knows his stuff and he’s not shy about telling you, so we would challenge each other, but that’s where we’d arrive at the best collaboration.

The other thing is that you’ve been living with this film for months, you’re so close to the material. Ilan is a fresh pair of eyes – and ears – to it, and his interpretation brings something very fresh to it.

It’s a very contemporary score too…

Yes, that was the intent. We’ve very much erred away from the sweeping orchestra to something that feels very contemporary and surprising. I was listening to the album recently and the score stands up on its own, it’s beautiful.

It feels closer to the narrative, too. It’s not window-dressing but really drives the pace and rhythm of the film…

Yes, it’s not about gilding the lily, but also we didn’t want to push the music – that would jeopardise it. With the Humans episode we talked in great depth about the music because we didn’t want to steer the audience into feeling something when the narrative was so strong anyway. We wanted the audience to come to their own conclusions, we didn’t want to steer their emotions. Ilan’s done that in a very subtle way and, for me, that’s what helps make it the climax of the series – you get to fall in love with our perfect planet and then you realise that that whole system is under threat as we destabilise it.

The Humans episode has a different format, doesn’t it…

Yes, and it’s quite a brave format. Firstly, it’s a conservation film. The Humans film bookends the series with the first episode, it starts with volcanoes and their CO2 emissions, and how it’s vital for life, but too much of it and it becomes a problem, and we have become a human supervolcano. We then go to examine the effects of that as it permeates to all the different parts of the planet and affects the other forces of nature.

We’ve very much tied it to the series but it’s such an important story – Attenborough opens it by saying it’s the most important story of our time – and one thing I really hope the final episode does is join the dots for people.

Photo by Huw Cordey (c) Silverback Films

It’s different, too, in that it introduces other experts, was that your idea?

Yes. It’s something that we tried on One Strange Rock and it worked very well, and there’s just something about having multiple viewpoints on such an important subject, and we’re grateful to the BBC for allowing us to be brave in that way.

So, we have Asha de Vos, the renowned marine biologist, who can speak with great authority about the ocean, and explorer and conservationist Niall McCann, who’s on the front-line saving animals from poaching and drought. So, we wanted to have people who are right in the thick of it to compliment David, who holds it all together.

It’s becoming integral to natural history programmes that it’s not just about beautiful pictures and seeing fascinating behaviour, there has to be an element of addressing the crisis we’re facing. It’s now a feature of Attenborough’s programmes, particularly, because he cares so passionately about it…

Yes, and he’s done programmes dedicated to it; Climate Change: The Facts, Extinction: The Facts. To my knowledge, I don’t think anyone’s tackled it as front on as we have in Humans, though. It’s a hard-hitting film, and I think it will grab people’s attention. We originally wanted to time the transmission with the COP climate change conference last November, but because of Covid and various things that wasn’t possible. For David himself, too, this film is also very important to him. He was making his film, A Life on Our Planet, at the same time as this, although I deliberately didn’t want to look at that while editing Humans because I didn’t want to be influenced by that in any way, we wanted this to feel specific to Perfect Planet.

Have you taken a different angle on climate change in this episode, then?

My aim in Humans, which I co-produced with Ras [Daniel Rasmussen], was to lead with animal-led stories. We wanted to draw the audience in emotionally, so we were keen to look at animals that are being affected by the changing of the forces. We filmed in an elephant orphanage in Kenya where many of the elephants are orphaned because of drought or floods. I had just had my second child when we were there, so I was in the paternal ‘new father’ mindset seeing dozens of these orphaned elephants, many of whom were close to death.

An orphaned elephant with his keeper at The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust’s nursery in Kenya. Photograph by Nick Shoolingin-Jordan/Silverback Films 2019.

They’re socially intelligent animals, and to be so young without parents, it was heartbreaking. But, significantly, seeing how important the human love and interaction was with their handlers. They look after them 24 hours a day, playing with them, feeding them, supporting them emotionally; they have become surrogate parents, and seeing that was just so moving, so humbling. That showed the good side of humanity. Even though we’re in trouble there’s still this army of heroes that are silently going about protecting wildlife.

We forget, too, that we think we’re a superior species, but if you look at the connection animals make with each other, and with humans, they are sentient creatures that have emotional needs much like we do…

It’s only when you see them in the environment that I saw them, that you’re reminded they are absolutely aware of pain and fear and distress from the situation they’re in. We all have the same right to be on this planet as any other creature, we’re not superior and, in fact, we’re as vulnerable as every other creature – as we ‘re seeing in this Covid pandemic. All the technology we’ve got can’t protect us sometimes.

The one thing I realised, with a mammal, you’d expect that sentience, but there was one story I filmed, near Boston and Cape Cod, about how warming oceans and changing currents are impacting turtles there. They head up for summer feeding but changing currents mean they’re driven further north, where it’s colder, and they’re experiencing hypothermic shock.

A critically ill Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle being given treatment at the New England Aquarium near Boston. Photo by Nicholas Shoolingin-Jordan.

We filmed a mass stranding where every year up to a thousand turtles are washed up on beaches there, freezing cold, and there’s an army of local volunteers who rescue them, and take them to the New England Aquarium. It’s like being in an episode of ER when it happens; dozens are coming in in various states, they have to have ventilators, adrenalin shots. They call it a mass casualty event. The shocking thing is back in the ‘80s they’d have one or two turtles, now it’s over a thousand at a time.

And, again, these turtles look you in the eye and you can see their distress. This is all because of our changing ocean systems, the warming temperatures and acidification of oceans, which are a direct result of the humans’ production of CO2.

Do you think we’re becoming desensitised to the environmental messaging we keep hearing and reading about?

I deliberately have not used the word climate change in the film, because we have become totally desensitised. We hear a phrase like ‘climate change’ and we tune out. I saw a TED talk about that entire subject and they’ve given it a condition, it’s called Apolocalypse Fatigue Syndrome. People are fed up with hearing about the apocalypse-

So how do we overcome that to ensure the message gets across and we make the necessary changes?

The problem is when we hear the word climate change or global warming it’s such a big thing that you feel you can’t do anything about it. So, I wanted to strip away that and use animal stories to bring you back down to earth and for people to then make the connection. So, rather than talk about climate change, we talked about the human explosion of CO2 and how that affects animals on the ground across the world. Our biggest issue is production of CO2. Of course, there are many environmental problems from habitat loss to plastics to pollution but by far the greatest change that’s happening to our planet is because it’s warming. And that’s something that we can solve.

I have to say, researching the Humans episode was testing on me because you realise how dire the situation is. But…the solution is in the planet itself. Ultimately those forces of nature we’ve got to know in the series are also the solution, certainly to the energy needs our expanding population requires, whether it be solar, wind or ocean power. That energy that life feeds off, there’s plenty of it to go around, more than we’ll ever need – but the switch over is not happening fast enough, 80% of our energy is still supplied by fossil fuels.

It feels like we know the answer, but what needs to happen for that to change?

Everyone thinks ‘but what can I do at home?’ But there’s a lot we can do. One long haul flight a year, for example, is the same as your entire carbon footprint from everything else you do that year. One flight.

The thing about humans is that we don’t change until our backs are against the wall. At the end of the Humans film we went along to one of the Friday marches, where schoolchildren were striking as a protest about climate change, and when you’re there and they’re holding banners saying ‘Our House is on Fire’ you realise their planet is in our hands. They know more about what’s going on than most adults because they’re tuned into it and connected through social media. They’re doing the things we should all be doing; they know you shouldn’t eat too much meat because of the carbon cost of it, for example. For me, it was really important to cover that and make that connection with the next generation.

Quite. It’s about the legacy we’re leaving for the next generation…

You can focus on crashing into the wall, but if you look at the road ahead you can steer the car from disaster. We’re at that moment now, we just need to get enough people in the car – it should be an electric car – to look at the road ahead, then we can make that shift for us to emerge as a species where we’re biosphere conscious – because we’re not at the moment – and I hope programmes like these, in their little way, go some way to making that happen.

A Perfect Planet ‘Humans’ airs on BBC1 this Sunday 31st January at 8pm – watch the whole series on BBC iplayer.

Photos courtesy of BBC / Silverback Films