The old priest was dying. He had been diagnosed with prostate cancer six months or so before, but it was too late. He was going to die.

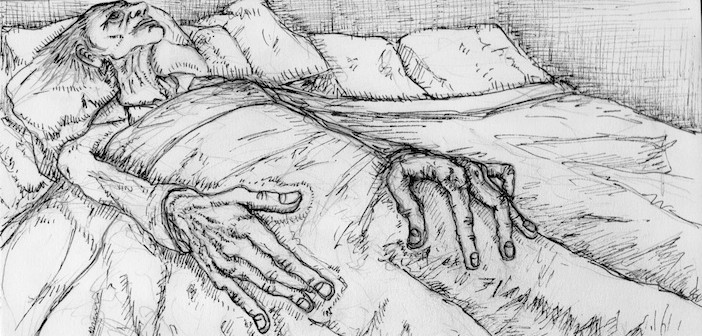

They had made a hospital bed up for him in the sitting room; it now resembled a ward. He was lying prone, his head on a mountain of pillows. His skin was taut, bloodless, his chin tilted up slightly, his mouth open. He resembled the alabaster statuary of some forgotten effigy on a medieval church sarcophagus. He was so still he could have been dead. But he was not dead, or forgotten. He was loved, and blood pumped through his veins, however feebly.

His daughter tried to rouse him. His jaw snapped shut, then sprung open like a weak-hinged trap. His head rolled on the pillows. You could see him trying to rip clear of the bland oblivion of morphine and dulled pain.

“Dad, you’ve got a visitor. Harry Chapman.”

I drew up a chair by the side of the bed, crouched forward expectantly, a faint smile of encouragement on my lips – which he didn’t see. Fragments of speech flew from his mouth as he grappled for lucidity. His opening eyes skimmed across me.

“You remember, Dad – he did the walk on the South Downs.”

A smile lit up his face. The first of many. “Ah, yes, I believe he’s a kindred spirit.”

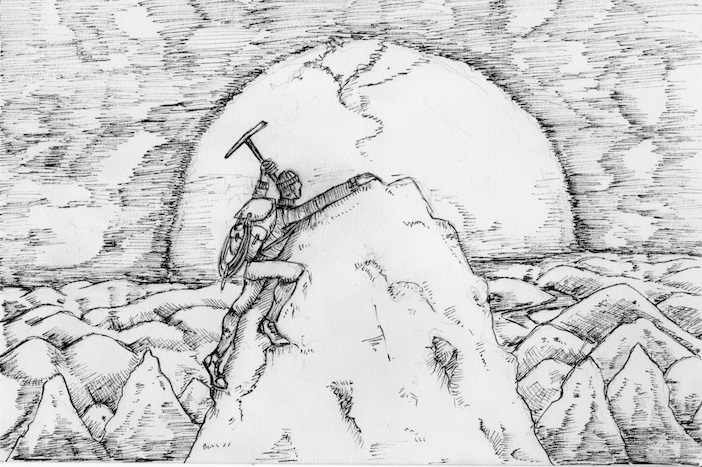

Sentences formed, at first snatches of reminiscence, then full-blown stories. He was back on the Pyrenees – fifteen, forty, fifty years ago – scaling sharp bluffs, glissading down slopes, crampons fixed to his boots, an ice pick in one hand, the Sun on his back, strength in his limbs and the gleam of life and adventure in his eye.

I felt I had done little to encourage all this; the occasional prompt, a well-timed question – but I suppose I clung to him in his meanderings when others may have turned their thoughts to dinner or the drive home, and I willed him on with my heart. I was some sort of catalyst for him and I was both honoured and humbled by the realisation.

“Dad, tell him about the time you were arrested by the Spanish police.”

“Dad, tell him about the time you were arrested by the Spanish police.”

“What? Ah, well, you see we were…”

But the story was never finished, despite his daughter’s best efforts to steer him back to it. But it didn’t matter, because something incredible was happening. As stories tumbled after stories, and digressions were hijacked by further digressions, the old man worked his way up in the bed so that he was in a sitting position. He gulped water, his eyes shined and the long bony fingers of his hands played out the scenarios. Youth and health were returning to his body. He was fighting the illness. Life was overcoming death. At least for a time.

More than an hour had passed, maybe an hour and a half, but his vigour and loquacity had not abated. But I could see he needed rest or he would burn himself out. I turned to my hosts, mother and daughter. They too were transformed. The grey despair which had crippled their faces was gone. They beamed with joy and gratitude, and perhaps some hope.

“Dad, I think you need to rest now.”

It was sad to stymie his enthusiasm, as once gone it might never reassert itself, but it was clear he was in danger of exhausting himself. I touched his hand to say goodbye and his daughter showed me out. We paused by the open front door. Quietly;

“That was incredible. Thank you. I haven’t seen him like that for months. Our families are inextricably linked now.”

I turned and left. I knew the occasion would be talked about for weeks and months to come, would enter family lore until those that knew it died and it was forgotten. Why hadn’t I gone before when he was more compos mentis, when we could have fully engaged, when I could have shared tales of my own adventures?

I resolved to return again as soon as I could, when I was next in the village.

Two weeks later though, he was dead.