As we adjust ever more to the ‘new normal’, Sarah Tucker considers how we’ve already been doing much of this since time immemorial…

‘Everything you need is behind the mask you wear’. Poignant and provocative words from the Dalai Lama as ‘masks’ and ‘bubbles’, the buzz words of politicians and journalists, are backhanded to each other like Federer and Djokovic in a Wimbledon final. Adjusting to every shop visit, remembering to carry one at all times in a sort of simulated Blitz, checking what is/isn’t allowed; being asked to wear masks and choose our bubbles feels like an imposition when, really, everyone has been wearing masks and choosing bubbles long before the virus.

The pandemic has merely polarised everything – inequalities, priorities and what is important – bringing them to the surface and exposing social constructs for what they are, irrelevant to life. When you are not working, a Saturday becomes a Monday becomes a Wednesday. Time has no meaning if you are not meeting anyone. It becomes rural, as you wake with the sun and sleep with the sunset.

Even the choice of the terms ‘bubble’ and ‘mask’ has been revealing. Bubbles are meant to be burst, popped and enjoyed. How ironic. And don’t we already live in bubbles? Of profession, age, demographic, nationality (Brexit was all about this), class and race? We have our bubbles of choice because we don’t want people to know what is going on in our own – or rather just the things we want them to. But being in an enforced bubble of family makes people more aware of categorisation. How it creates limiting beliefs and opportunities and smudges what is important (health) and what isn’t (everything else).

While I’m on it, the concept of ‘key worker’ has also been interesting. ‘Key’ as in they are important to health – mental and physical – but, by implication, that definition means everyone else is not key. Not important. Indeed, when shops re-opened, they were described as ‘non-essential’. Read that again. They are non-essential. You don’t need this ‘stuff’, you are just manipulated to want it. I’ll leave that with you.

And then we have the masks.

Historically, masks are there for ornament, protection and anonymity. Perception is everything and yet people, everyone, hides behind a mask to hide how they want to appear to others. So, although we have been wearing masks – or most of us have – for our protection and those of others, we have already been doing this since time began.

A mask is something to hide behind when you are afraid. When you don’t want people to know who you really are, what you think and what you say. But physically it is, ultimately, stifling – it blocks the breath and the voice; issues which have an immense psychological impact on the individual and those around them.

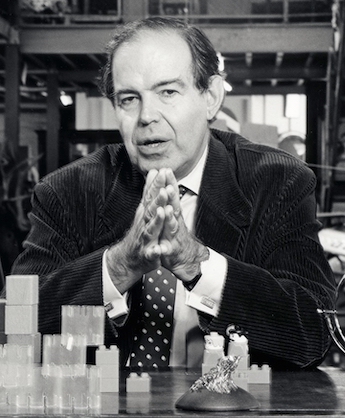

The use of words – key, mask, bubble – is one of the limitations acclaimed physician and psychologist, Edward de Bono, mentions in his books. Now in his 87th year, with as many books to his name, and still going strong, de Bono most recently put forward the idea of children learning how to think in schools rather than what to think. Again, something that has right to the surface of debate with the current grades crisis affecting young people across the country.

De Bono’s success has mainly been with business and commerce – who have made and saved millions from introducing his thinking techniques – and, in writing and researching his biography over the past two years, I realise his ideas have never been more relevant, and his views on politicians, professions – and children – more on point.

De Bono’s success has mainly been with business and commerce – who have made and saved millions from introducing his thinking techniques – and, in writing and researching his biography over the past two years, I realise his ideas have never been more relevant, and his views on politicians, professions – and children – more on point.

‘We are better when we think, we are better than we think’ is one of his oft-quoted phrases. And learning how to think creatively bursts bubbles and removes masks quicker than anything else. It breaks down the illusion of what is important and what isn’t. To that effect, business loved his ideas, while politicians were afraid of them (after all, the last thing politicians want is transparency), children adored them (because he made learning how to think fun), and education (in the UK at least) largely dismissed them, because the way we educate our children, the way the media aligns, is through critical thinking, not creative or lateral thinking.

It is based on the original premise of Aristotle (all about putting people into boxes – read ‘bubbles’), Plato (to find the ultimate truth on which all religions and political parties are founded – although there is no such thing) and Socrates, who loved a good argument, based everything on absolutes. Education does this. As does the law. As does the journalist. That is the issue with critical argument – it is combative, judgemental and limiting. The opposite of collaborative and creative thinking, which is what De Bono expounds.

The result, as De Bono explains in his book The Happiness Purpose, is that we have not improved our thinking for centuries. Thinking is a skill which can be learnt. It is a skill which, more than anything, burst bubbles and removes masks, to identify who and what is important. Indeed, he describes politicians as being unable to think because they have an over-inflated bubble of ego; ‘A world-weary, know-it-all, lived-out individual has usually done everything and enjoyed nothing’. This pointed appraisal could also be relevant to those in any level of senior management who has lost their way.

When you learn how to think, you ask better questions of yourself and others. You become aware there is no certainty, only a need for clarity, and that is what you seek. You understand there are no absolute truths, only ‘proto-truths’ – temporary truths – which are expanded upon as information and collaboration grows. And that anything is possible, probable, and the best way to learn is to provoke and observe – not to judge.

Indeed, as an author of fiction novels and non-fiction books for children, while researching de Bono’s life, I wrote a parenting manual for children, but turned the concept on its head and made the book (Fourteen) for teenagers to help them manage and understand their parents. Working with fourteen-year-olds for over seven years, having a father who was a head teacher, and friends who are teachers, the issue of the child is always because of the issue with the parent. Un-PC to admit, yes, but ask any teacher. If they, for one, take their mask off, they’ll tell you the truth – and burst your bubble. Not in a judgemental way, I should add, but by observation.

Indeed, as an author of fiction novels and non-fiction books for children, while researching de Bono’s life, I wrote a parenting manual for children, but turned the concept on its head and made the book (Fourteen) for teenagers to help them manage and understand their parents. Working with fourteen-year-olds for over seven years, having a father who was a head teacher, and friends who are teachers, the issue of the child is always because of the issue with the parent. Un-PC to admit, yes, but ask any teacher. If they, for one, take their mask off, they’ll tell you the truth – and burst your bubble. Not in a judgemental way, I should add, but by observation.

Thinking, and learning to think, is fun. I’ve been using the lockdown to read countless books on thinking – actually, I have counted and it’s over a hundred – many of which have copied or morphed de Bono’s original work. He was, and still is, before his time, wanting to introduce thinking classes into schools. In Singapore, ‘thinking classes’ in schools are mandatory. We’ve tried similar in the UK in the ‘80s (think ‘Education, Education, Education’) and under Tony Blair, but they’ve never caught on. Perhaps that’s our innate cynicism.

It is also simple. De Bono made it simple. And simple isn’t stupid – it’s clever. As I’ve learnt, reading his books, he is an observer. Visionary, missionary, writer but, above all, observer. He realised children observe everything, but they are educated to increasingly stop observing and start judging. Media, law, politics, business is all about judgement, comparison. The problem when you stop observing is that you stop learning and growing and become easier to manipulate. Someone who observes is not in a bubble – they are always outside it. And they don’t tend to wear masks. They just notice everyone else is. And there are tell-tale signs. Take, for example, the use and misuse of jargon.

Anyone who uses jargon is trying to outwit, and more often than not they use this mask to hide what they mean. I once listened to a panel on BBC Question Time where the acclaimed historian A J P Taylor explained a complicated treaty with incredible alacrity and humour. I only wished he had been my teacher at school. It takes a real genius to explain something complicated and make it accessible to the masses.

De Bono does that just as Taylor did then. Which explains why academics hated him, politicians feared him, and children were fascinated by him. He brought clarity. He removed masks of convention and pomposity – and jargon. In short, he burst bubbles. He brought transparency. He made everyone equal. He let everyone play – and he made it fun. Compare this to many academics and all politicians who blast us with statistics and you realise who are wearing the biggest masks and have the biggest bubbles to burst. We have been defined and categorised, and it creates a climate whereupon we willingly and knowingly put ourselves inside that bubble. Now, with no amount of irony, we are physically wearing masks and getting into our bubbles – albeit this time with just cause.

De Bono does that just as Taylor did then. Which explains why academics hated him, politicians feared him, and children were fascinated by him. He brought clarity. He removed masks of convention and pomposity – and jargon. In short, he burst bubbles. He brought transparency. He made everyone equal. He let everyone play – and he made it fun. Compare this to many academics and all politicians who blast us with statistics and you realise who are wearing the biggest masks and have the biggest bubbles to burst. We have been defined and categorised, and it creates a climate whereupon we willingly and knowingly put ourselves inside that bubble. Now, with no amount of irony, we are physically wearing masks and getting into our bubbles – albeit this time with just cause.

In short, we need connectivity. In his London soirees, De Bono met many educationalists, business men and politicians, listening to voices from different professions – different bubbles, if you will – realising the only way to effectively burst the bubbles and unmask the agendas of each was to allow them to speak with people they saw not as a threat but those who were in different professions. ‘The soirees allowed the bubbles to burst, people to speak openly, honestly,’ he says with a smile. These soirees, incidentally, were recorded; his ex-wife has copies of them safely in her loft, which will probably go with Edward to his grave, so we may never know whether these pioneers of the professions will ever have unearthed the secret to.

I offer the last word to Baroness Helena Kennedy, who has written the introduction to my De Bono biography, identifying the need for increased use of lateral thinking in one profession you might think already foolproof; ‘Connectivity is the key to moving forward in our thinking. Law would certainly benefit from more of it.’

In truth, we could all benefit from it. Especially now.

‘Love Laterally – The Story of Edward de Bono’ by Sarah Tucker is published by Sandstone Press and is released this Autumn.