In this feature-length double bill, Tom Garton continues his (mis)adventures in ‘the ‘stans’. Having spent a week in Kyrgyzstan’s capital and the surrounding valleys, he and his still ailing friend, Ben, continue their holiday in Kazakhstan. Well, we use the term ‘holiday’ loosely…

“Where is he?!”

We’re slumped on the side of a dirt track, Ben is lying in the dust, I am pacing up and down. Across the road from us, the wizened owner of a kiosk selling Cokes and nuts has fixed her stare on us in quizzical suspicion. A group of young car mechanics has also assembled a few feet away from us and is now hurling insults at us in Russian.

It’s been almost two hours since we got out of our driver’s minivan in Kyrgyzstan and crossed the border on foot. I’ve since forgotten what the guy’s number plate is. I’m convinced he’s run off with our bags.

“I’m sure he’ll be here soon,” Ben replies nonchalantly. He heaves himself off the ground and barks a riotous, hacking cough. His bronchitis hasn’t gone.

“What are you doing?” I ask.

“I’m going to have a chat with those lads over there,” he gestures to the abusive mechanics jeering at us.

“Why are you doing that? Just stay here.” But he’s already gone.

What was I doing here? This was my summer holiday. I’d spent hundreds of pounds on vaccinations for exotic diseases like Tick-Born Encephalitis and Rabies, on the assumption that we’d be riding horses through the steppe. I’d bought new waterproofs, hiking boots, and water purifying tablets. I even had a compass. I’d used none of them. For the past week we’d been stuck in Kyrgyzstan’s capital, eating Italian food, going to the gym, and having disgusting massages.

I could have been in Tuscany, or Croatia, or the Cote d’Azur. Instead, I’d gone on a city break to Bishkek.

Now, on the final leg of these grueling two weeks, we were heading to Almaty, Kazakhstan’s biggest city. We’d have to stay there for the next few days. With Ben’s bronchitis still playing up, we wouldn’t be able to spend time camping in the steppe as we’d planned, and so we’d have to remain in the city. Not that that bothered me. I didn’t want to run the risk of getting lost and missing our flight. I just wanted to go home.

“They’re Man City fans!” Ben shouts at me from his conversation with the mechanics.

“I am Chelsea,” he pronounces slowly to them, pointing at himself. I don’t think he’s ever watched a Chelsea match.

Our driver arrives, and apologises for his lateness. He got stuck with the border guards. I drag Ben away from his involved conversation and we set off.

As the sun sets, the rolling, yellow hills of the steppe stretch out indefinitely. There are no towns or cities, yet mysteriously we occasionally speed past a lone cyclist or pedestrian.

We arrive in Almaty at night. It’s a very different city to Bishkek. The outskirts are populated with American fast food chains and malls. There are skyscrapers, and well-built roads.

We approach our hotel, the Ritz Carlton, located in a monolithic, black skyscraper overlooking the mountains. After our time in Kyrgyzstan, you can almost smell the dark, steely, intoxicating aroma of money.

“Bloody hell,” Ben says, as our driver parks up in his minivan alongside the black Rolls Royce and Mercedes. The hotel’s entrance is shared with a Bentley showroom.

I look terrible. I’m wearing the traditional gold-green felt chieftain’s coat I bought in the bazaar in Bishkek. My hiking boots are wrapped in plastic bags, hanging from my backpack.

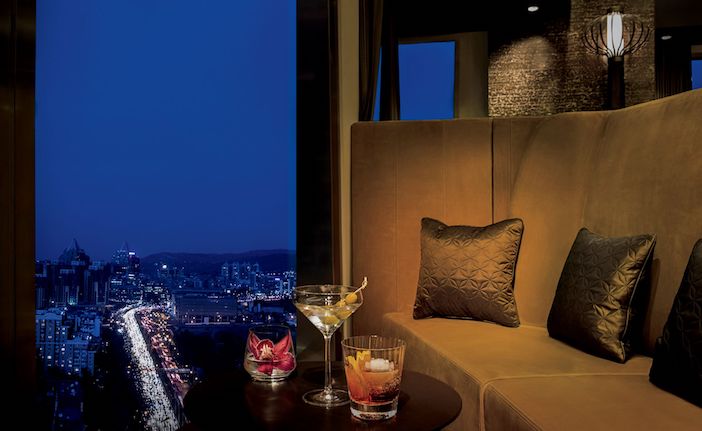

The doormen are bemused by our appearance, but send us up to the hotel nonetheless. The lift takes us to the hotel reception on the 30th floor. Floor-to-ceiling windows offer breathtaking views across the city. The traffic meanders like a fluorescent river several hundred feet below. Artwork is inspired by the area. A horse’s head sculpture sits on a plinth by the lobby desk. The reception hums with a quiet, purring, self-confident busyness.

“Mr. Garton? We’ve been expecting you.” The receptionist smiles at me with flawless English, ignoring my incongruous outfit and sweaty brow. “Please, follow me.”

The rooms are decorated in cream and dark-brown wood. The low lighting on the dark wood floors and furniture creates a soothing, maroon atmosphere. The linen is the kind of crisp, expensive stuff that you stretch out on. Every convenience is offered: climate control systems, Plasma TVs, speaker systems, and espresso machines. The bathrooms are marble grey, stocked with Asprey products.

The huge windows, the same as those in the reception, show us night time Almaty, sprawling out before the mountains.

“Do you fancy a night on the tiles?” Ben asks, cracking open a Diet Coke from the mini bar and flicking on the BBC World Service. We didn’t go out in Bishkek because Asyl warned us to stay inside after dark, and Ben was malingering.

“Why not.” I reply.

We get ready and head down to the reception. Once we’ve showered, and put on some half-decent clothes, we look slightly more like guests at the Ritz Carlton.

We take our recommendations from the concierge. A table is booked at EAST, an upmarket, pan-Asian restaurant next door to the hotel.

We immediately regret going to EAST.

EAST is awful. It’s more like a tacky Leicester Square nightclub than a restaurant. It has a cavernous atmosphere created by ludicrously high ceilings. Its near pitch-black lighting makes it impossible to see your menu, food, or waiter; and an indistinct, pounding soundtrack of deep house means trying to have a conversation is futile.

Overall, the effect is highly disorientating, so when the waiter comes to take our order, I blindly take his suggestion without hesitation. Ben orders a vegetarian noodle dish.

Once our waiter’s gone, I get a chance to look back at the menu to see what I’ve ordered. A seafood platter?

What’s a seafood platter doing on the menu in Kazakhstan?

Flicking through the menu, I notice that it is almost entirely composed of seafood and fish. In fact, more than half, perhaps even two-thirds of all dishes are fish-based.

But where are they getting this fish from? This is the largest, land-locked country on the planet. The closest access point to the sea is in Turkey. That’s a four-hour plane journey. That’s as far from Turkey as the UK is to Turkey. So where are they finding sushi-grade raw eel, raw salmon, and raw tuna for their sashimi?

Our dishes arrive. I’m hesitant to eat my seafood platter now, having thought about the journey that it must have taken to get here. But we’re hungry, and it’s bloody expensive. It may not match the price but, miraculously, it’s edible.

We reluctantly pay up, and take an Uber to Sky Bar, the other suggestion of the concierge.

We pull up outside the nightclub. There’s a long queue outside, but we enter immediately without resistance, ushered in quickly and are suddenly placed in a lift.

The club is on the top floor of a building. It makes a conscious effort to seem Western. There are several bars dotted around, with signs of American and European cities above them. Amsterdam. Paris. London. New York. The DJs play dance music, and Western 80s tunes.

We start talking with a group of locals. They all speak good English. They’re surprised we’re here in Kazakhstan, and effuse about London.

There are three ethnic-Russians (a woman and two men), and four ethnic-Kazakh women. As we talk more, an interesting discussion emerges about national identity in Kazakhstan against the backdrop of Whitney Houston’s I Wanna Dance With Somebody.

The ethnic-Russians explain they are Russian, not Kazakh; but were born in Almaty and would feel out of place in Moscow. The ethnic-Kazakhs, meanwhile, explain they are Kazakh.

It’s fascinating. It seems there is an unusual disjunct between nationality and geography. It’s almost as if the land-mass of Kazakhstan doesn’t connote the same sense of national identity as other parts of the world. Being born in Kazakhstan wouldn’t necessarily make you Kazakh.

Some have suggested this is because of Kazakhstan’s historically loose sense of place. For millennia nomads roamed across the steppe, divided into different tribes. The region saw the constant transit of invaders, travellers, and immigrants along the Silk Road.

This geographical looseness was compounded by the Soviet Union, where nationalities from across the USSR were sent to Kazakhstan to work, particularly during Khrushchev’s Virgin Lands scheme. As a result of this history, culture isn’t necessarily tied up with place.

There’s a risk, of course, one would imagine, that this notion, i.e. that being born in a place doesn’t confer you with national identity, could run the risk of fostering xenophobia, and ethnic nationalism. But here it doesn’t appear to. What’s really going on in Kazakhstan is a psychological divide between nationhood and geography. In theory it almost embraces a borderless world, where your culture is created by your family not your geography.

Tom’s time in Kazakhstan continues tomorrow, when a calming excursion into the countryside turns into a birthday with border guards…