We have a travelogue with a difference over the coming weekends; serialised in three parts, ex-army major Philip Cottam takes on one of skiing’s most notorious challenges, the 120km tour known, simply, as The Haute Route…

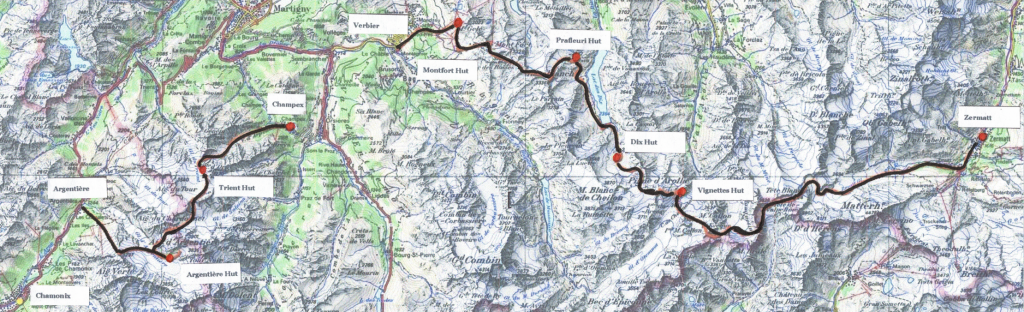

The Haute Route, the High-Level Route, from Chamonix to Zermatt, is deservedly the most famous ski tour in the European Alps and should be on the tick list of anyone seriously interested in ski mountaineering. The scenery is never less than superb, the skiing frequently exciting, the physical demands exacting and, if you decide to knock off a few peaks on the way, there are adrenaline surges to be had and views to die for. It usually takes six days to complete the 120 kilometres or so of high mountain terrain involved.

There are as many as ten high mountain passes and over twenty glaciers to cross as well over 20-30,000 feet of ascent and descent to manage depending on the precise route taken. Created in the mid-19th century as a long-distance summer mountain walk by members of the English Alpine Club, the Haute Route was successfully completed on skis for the first time in 1911 by a group of mountain guides from Chamonix. Although it is far busier now than it ever used to be it still remains the serious undertaking it has always been.

The usual starting point is at Argentière, a short distance up the valley from Chamonix. Although most people stop when they get to Zermatt the really dedicated often take an extra day to cross over the Adler Pass and finish in Saas-Fee. The precise route can be varied to suit the experience and skills of the party. That said, the weather and snow conditions are usually the deciding factors. They frequently temper the ambitions of even the most experienced and determined of parties. The lucky can fly across the route with blue skies every day, perfect snow conditions and no trail-breaking because others have already done the hard work.

However, the Route should never be underestimated. A disaster in 2018 saw seven people die in a storm only a few hundred metres from the Vignettes Hut. Weather can change rapidly for the worse, visibility deteriorate into a complete white out and snow conditions become dangerous, so it is wise to work out escape routes in advance. When conditions become uncertain there is no shame in retreating to the safety of the valleys or one of the mountain huts until they improve. The mountains will still be there when they do.

Abseiling down the Fenêtre des Chamois

Warming Up

The principal prerequisites for attempting the Route are a high level of fitness, some experience of off-piste skiing and confidence when faced with steep ground. You will find yourself not just skiing down steep slopes but possibly having to abseil down them, climb up them with your skis tied on your rucksack and on occasion doing kick turns in deep snow. You may also have to ski roped up on occasion. This is to be avoided, if at all possible, most especially going downhill, as the result is usually a slow-motion version of the Keystone Cops, but far less amusing, especially for those involved. Overall, it is better to be a confident skier than an experienced mountaineer as the basic skills needed for the latter can be taught more quickly than the time it takes to improve skiing techniques.

That said, if the party does not employ the services of a qualified mountain guide – most do these days – it is essential some members of the team have alpine mountaineering and ski-mountaineering experience. My own party of four were fit and experienced skiers and two of us were also experienced alpine skiers and mountaineers. Before setting off on the route it is important to practice skiing with rucksacks as well as doing some crevasse rescue training and avalanche safety drills especially with avalanche transceivers. I would also recommend visiting the Bureau des Guides to get the latest reports on the weather and snow conditions. We also carried out some snow pit tests to determine the approximate stability of the snowfall that year.

As part of the training you can also ski the Vallée Blanche. It begins with a spectacular cable car ride in two stages to the summit of the Aiguille du Midi which must provide some of the best views in the Western Alps. There is then an adrenaline raising walk to where skis can be put on. Exiting out of a tunnel one immediately finds oneself on a narrow snow ridge with a long steep drop on the north side and a shorter but still exciting drop on the south side. For the unprepared it can come as a bit of a wake-up call. Once skis are on there is fun skiing over open slopes with fantastic views in every direction. The only really tricky part is getting through the icefall. Care is needed navigating this and much will depend on the snow conditions and the time of year. Thereafter everything eases up. It used to be the case that you could always ski to just below the hotel and railway station at Montenvers and if you were really lucky you could even ski all the way back to Chamonix. With global warming this is far less likely.

On the open upper slopes of the Vallée Blanche

Setting Out

Most parties start by taking the lift at Argentière up to the Grands Montets before skiing down to the Argentière glacier. A very small number will disdain the lift and flog up all the way from the roadside. As Eric Roberts remarked in his classic 1970s guidebook this is really only for ‘fanatical purists and impecunious parties’. For some reason that I cannot remember we decided it would provide useful additional training. The holiday skiers flying down past us must have laughed at these four beasts of burden struggling slowly upwards under the weight of their rucksacks. Even though we had spent hours arguing about what equipment and food we could do without they were still heavier than we really wanted.

It was a relief when we finally made it to the Cabane d’Argentière. After the tough start we had given ourselves we decided a reward was in order. Instead of cooking some of the spaghetti that was to be our staple diet for the trip we opted to purchase steak frites from the guardian and break open the bottle of wine I was carrying in my rucksack. We then sat outside to admire the dramatic view opposite of some of the great ice walls of the Alps – the north faces of the Triolet, Courtes, Droites and Verte – some of which have been skied down since then. Nowadays many parties having taken the lift from Argentière up to the Grand Montets miss out the Argentière hut altogether. To save a day they head directly for the Cabane du Trient via the Col du Chardonnet or the Col du Passon.

Blast wave of swirling snow hundreds of feet high created by a serac fall

We made a reasonably prompt start the next morning and headed down to the beginning of the 2,500 foot climb up to the Col du Chardonnet via its eponymous glacier. We were making good progress up the steep lower slopes towards where the glacier flattens out when Zak, who was breaking trail at this point, said he had started to hear the occasional creaking sound. We all stopped to listen. Zak was not mistaken. This was not good news. It meant that below the new snow we were struggling through there was what is called wind slab which is notoriously prone to avalanche.

Wind slab is usually found on lee slopes or where there have been sustained cross winds. It is so-called because snow crystals that have been polished by the wind form a cohesive slab or slabs of snow that do not become fully bonded to the layers of snow below and can break away. It is also not always immediately obvious especially when overlaid by new snow. Sometimes the extra weight of new snow on its own is enough to overload the bonding and precipitate an avalanche. The vibrations that skiers inevitably create, whether ascending or descending, can also weaken the bonding. If you hear a hollow creaking sound you are probably on wind slab.

This was certainly not what we were expecting as it was an unusual place to come across it. There was clearly a danger we might precipitate an avalanche if we carried on exactly as before. We then discussed what to do. Should we go on or should we go back and if so, how? It did not take long to come to a team decision.

Philip’s adventure across the Haute Route continues next weekend as he and his team mates negotiate a wind slab and have an encounter with the Swiss Army…

Photographs by Philip Cottam and courtesy of International Alpine Guides who run tours of the Haute Route. For more information, please visit www.internationalalpineguides.com.