At what would normally be the time of year to make predictions for the next, author and travel writer, Sarah Tucker, reflects and takes a daring view on what the world will offer once the pandemic lifts…

Traditionally, the beginning of November is the time of World Travel Market, which sees tens of thousands in the tourism industry and media meeting their like at the cavernous echoing space that is London’s Excel. By the end of the week, feet in agony, brain saturated, I’d be sounding something like Minnie Mouse meets Eva Gabor, having lost my voice shouting my way through interviews at exhibition stands, competing with raucous traditional music or cookery events next door. ‘WTM’, as they call it, is as exciting as it is to be endured.

It is here I would ‘discover’ the travel trends, admittedly researched by those who have an interest in travel – promoting it, I mean – so I was always left with a little scepticism as to the veracity of these recommendations and guesstimations, some of which ranged from the bizarre – the ‘kidnap’ experience in 2008 was a real highlight – to the obvious, lest we forget the recommendation for ‘overseas’ travel in 2004 (yes, really – although, ironically, that will likely become a trend again in the next ten years or so).

And, as we make the most of our staycations, it’s the invention of new words I always await with abated anticipation. And this year is no different. ‘Celestial escapes’ are not a one-way trip to heaven, nor trips in the exclusive company of Brad Pitt/Scarlett Johansen, nor even into space, as you might think, but refer to ‘wilderness tourism’. Although, given the world has lost a third of its wilderness in the past thirty years according to Saint David (Attenborough), you can see where the celestial element comes from, a sort of ‘get it while you can’.

The serious point, though, is that we destroy what we ‘discover’ – and we travel journalists are the weapon of mass destruction. So, my view is to leave wilderness alone, and that includes the cultures which slice it up for paddy fields (Madagascar et al), farmland (Brazil) and property development (everywhere). Besides, a tourist’s understanding of what constitutes ‘wilderness’ is usually a goldfish bowl of a safe perspective where the nasty spiders, snakes, or anything that challenges your place in the human food chain, doesn’t enter the equation anyway – so why bother.

The same goes for the next anticipated growing trend, which is nomadic tourism – which, for most, translates as ‘glampervan’ journeys. Hmm. A campervan holiday is like buying a property in the countryside, which a lot of my friends and acquaintances have been doing over the past few years. Although their perception of what constitutes countryside varies from the ‘deep rural in France’, to village-five-miles-out-of-major-city-of-architectural-importance. Even more so now everyone who lives in the city is like an incubus of plague, and they are all heading to the potting shed of England that is Bath and its environs. They have bought into the press release that life is better/cleaner/more authentic in the countryside, because John Craven every Sunday afternoon says so, when the reality is more Withnail & I than Babington House.

I once took a campervan – or RV, as they call them in North America – with teenage son around the ‘top of the world trip’ in Canada. Fabulous views, sure, taking your mind off the cramped conditions, but aforementioned son was stuck to his iPhone, head down, and I was wondering where next petrol station was imminent as I didn’t want to be stranded in wilderness (there is some genuine wilderness in the Yukon) as we would undoubtedly then see a lot of grizzly bears. Admittedly, there are not many grizzlies in the wilds of England, but there are some not very friendly locals who have made it known to all and sundry, including their own tourists boards, that they don’t want you there – especially if you’ve been one of those incubus-of-plague city dwellers.

Then there was the ‘cultivacation’, or eco-tourism trend, an oxymoron which the travel industry and audience have yet to catch on to, although it’s been a trend allegedly for the past five years or so as Sir David’s voice and documentaries have become less like worse case scenarios than historical timeframes. The best way to be an eco-friendly traveller is, erm, not to travel. To stay put, not as in staycation, but to be in isolation. So, effectively, Covid has done more for eco-friendly tourism than any political mandate – unless you conspiracy theorists out there count Covid as a political mandate.

Authentic, wellness and mindful tourism have been rebranded as trends to ‘community immersion’, ‘longevity retreats’ and ‘co-working camps’. ‘Community immersion’ genuinely did make me smile; I remember the banner which the Cornish locals pinned over a bridge en route to their fabulous county telling visitors from anywhere else in no uncertain terms where they wanted them to go – and it wasn’t Cornwall. Covid has not brought out the best, or worst, in people – it has brought out the truth. So, community immersion is, ideally, in a community where they want you to immerse yourself in their culture. Not one where they don’t. Remember, if these places could find a better way of making money than having you visit them, they would!

And longevity retreats. I fell off my chair at that stage. As a yoga instructor in schools and clubs, and someone who has written about retreats, spas, variations on that theme, longevity comes from peace of mind, regardless of geography. It comes from lineage, diet, attitude, perspective. Taking your emotional baggage from place A to place B still means you have that emotional baggage on the way back, it just feels lighter and its effects disappear quicker than the tan.

And co-working camps. This sounds more like concentration camps than mindfulness holidays but perhaps that’s just my take on it. Giving back to the community is not a holiday, it is an experience. It is something you invest in, and come back feeling, often, that you need a holiday because you realise how much work and time it takes to make the places you visit look so good. Both of these feel like misnomers at best, paradoxes that have good intent behind them but which need more thought in their application.

The truth is no-one really knows what the trends will be in 2021. My guess is as good as yours. I would like to believe people will be more appreciative of travel, having forgone the pleasure of being able to travel. The uber wealthy will have foregone nothing, so they will be just as unappreciative, self-serving, sociopathic and sanctimonious in their self-imposed bubbles as they ever were. They know how to look after themselves and they don’t care if the locals don’t like them in the places they frequent. They pay for them to like them, as they do everyone else.

I would like to believe Sir David, Greta et al will have won their battles not only with the super powers of the world, but the masses who have, if only they knew it, the real power, and realised if they continue to travel the way they do, or did, that they will leave nothing to experience and appreciate.

For the rest, I believe, depending on how long the stop-start-stop Hokey Cokey of Covid/Brexit (and Brexit will have an impact on travel too), people will always want the guaranteed sun of overseas. When bombs went off in the London Underground and we had to be more vigilant about packages on the seat next to us, and there were polite and ominous sounding announcements about delays because an unsuspected package had been seen, I remember listening to other commuters complaining they would be late for work. As the summer exodus showed this year, even a pandemic and the prospect of agonising death, won’t stop the British from wanting their summer holiday. Many, financially pinched by the pandemic, will stay put not because of environmental reasons or to help the local economy but because they have no choice. And although there will be travel companies who will have disappeared, there will be others that will take their place, with a more flexible and robust business model – because it will need to be.

For the rest, I believe, depending on how long the stop-start-stop Hokey Cokey of Covid/Brexit (and Brexit will have an impact on travel too), people will always want the guaranteed sun of overseas. When bombs went off in the London Underground and we had to be more vigilant about packages on the seat next to us, and there were polite and ominous sounding announcements about delays because an unsuspected package had been seen, I remember listening to other commuters complaining they would be late for work. As the summer exodus showed this year, even a pandemic and the prospect of agonising death, won’t stop the British from wanting their summer holiday. Many, financially pinched by the pandemic, will stay put not because of environmental reasons or to help the local economy but because they have no choice. And although there will be travel companies who will have disappeared, there will be others that will take their place, with a more flexible and robust business model – because it will need to be.

Those who have holiday homes overseas will appreciate them more, or profit from them more, likely renting them out to couples who wanted to try before they buy into a rural idyll which is nothing like the programmes on daytime TV that inspired them. Social distancing, which has never been an issue with the reticent British, will suit those in search of walking/cycling/trekking holidays where you collectively tick all of the boxes of eco, mindful, wellness, authentic, nomadic, wilderness trends in one bang, not to mention keep us in agreeably-sized groups.

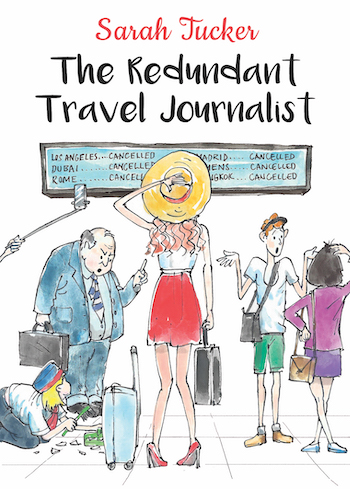

In my novel The Redundant Travel Journalist, I suggest airports be turned into schools, where those children who work really hard are rewarded with holidays overseas as opposed to A***. A fantasy, perhaps, but the idea is that you literally see where your hard work – and trying hard – takes you in life. And that is how it should be. When we identify a travel trend that shows we have learnt our lesson from this pandemic, and why we want to travel in the first place, and if it is actually good for us as a global collective to travel, perhaps then we have learn the greatest lesson of all and realise the meaning of that oft quoted platitude ‘life is a journey, not a destination.’

For more information about Sarah and her work, please visit sarahtucker.info.