As the critically-acclaimed celebration of the French visionary enters its final fortnight, Harry Chapman makes a late call to the exhibition the London Evening Standard called “an aesthetic boxer’s blow to the heart”…

In 1814 when Honoré Daumier was six years old, his father, a ‘glazier’ (a dealer in frames and decorative tableaux), moved to Paris from Marseille to seek his fortune as a poet. Two years later his wife and young Honoré travelled there to join him. Daumier senior found favour with the king but his success lasted precisely a fortnight. Thereafter he fell into poverty and despair. He was to die at Charenton, the infamous lunatic asylum in which the Marquis de Sade had also ended his days.

‘The Third-class Railway Carriage (Un wagon de troisième classe)’, 1862-64

It was a harsh lesson for his son who was not only forced into early employment by his father’s confinement, working first as a messenger boy for a bailiff and then as a book seller’s clerk, but showed him the folly of pursuing too closely one’s dreams. For Daumier wished to be a painter – a dangerous desire for one coming from such straitened circumstances.

The creative pull was too strong to resist though and eventually he settled on a compromise. In 1825, at the age of seventeen, he was apprenticed to a lithographer. Thereafter he began to receive commissions and in 1830 he began contributing to Charles Philipon’s weekly satirical newspaper, “La Caricature” and its successor, “La Charivari”. Unintentionally Daumier had become a cartoonist and satirist and was soon to develop into a very accomplished one. Like many writers and painters, it was the events and materials of his childhood which were to provide the engine and substance of much of his work. Having been one himself, he had a natural empathy for the poor and downtrodden, a horror of authoritarianism and injustice and, perhaps because of his father’s downfall, a fascination in the tension between real and imagined worlds. The former was to be expressed in the waspish visuals of his newspaper lithographs, the latter more quietly in the slow development of his painting.

‘Gargantua, La Caricature’, 16 December 1831.

The RA show is the first major retrospective of the artist to be held in Britain for more than fifty years. For such a prolific artist (he produced more than 500 paintings, 4000 lithographs, 1000 wood engravings, 1000 drawings and 100 sculptures) who enjoyed some renown in his lifetime, this is surprising. But Daumier has always had a tricky relationship with the public and the critics. That an artist could have such a sustained and successful career as a political satirist may have led some to write him off as a ‘serious’ artist. In some ways Daumier himself may have been to blame. He submitted very few works to the annual Salon, success in which could make an artist, and he turned down state commissions when he found the subject matter uninspiring. He was no showman. He didn’t curry favour and would prefer to spend his free time “drinking cheap wine with barge captains”. In a profession where flamboyance and an inclination to use elbows and knees to clamber up the greasy pole were needed, his reticence was a hindrance. The editor Pierre Véron remarked,

“I could never understand how Daumier, so assertive, so revolutionary when holding a pencil, could be so shy in everyday life.”

It was to his fellow writers and artists that Daumier owes his reputation. Baudelaire, a personal friend who lived round the corner from him in the working class district of the Quai d’Anjou on the Ile Saint Louis, described him as one of the most important men “in the whole of modern art”. A year before his death in 1879, thirty of his friends, led by Victor Hugo, organised a retrospective of his work at the Galerie Durand-Ruel. The exhibition focused on his paintings and drawings, most of which had never been seen before in public. The show was a failure. But it did introduce Daumier to the new generation of aspirants. Van Gogh raved about him in letters and Degas was to go on to collect 750 of Daumier’s prints, five drawings and a painting. His influence can be seen in the works of Picasso, Paula Rego and William Kentridge. Contemporary cartoonists Quentin Blake and Gerald Scarfe have recognised their debt owed to him whilst Peter Doig has been blatant in his admiration, homaging Daumier’s “The Print Collector” in his own “Metropolitain (House of Pictures)” and “After Daumier”.

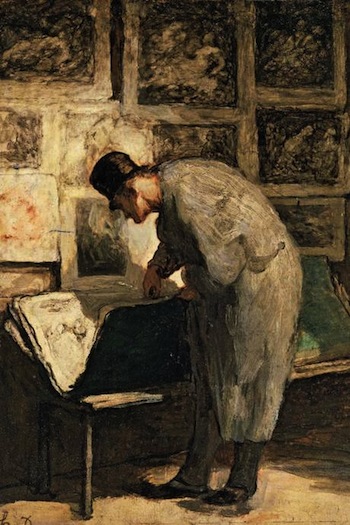

‘The Print Collector’ (c. 1857-63)

Daumier would no doubt have been flattered but also creatively stimulated. One of the great interests reflected in his work was the place of the artist and his art, the act of looking and the power of the beholder. “The Print Collector” (c. 1857-63) – a small masterpiece of atmosphere – is just one in a series of contemplative paintings and kinetic cartoons which examine the relationship between art and the viewer and the art of looking itself. Daumier was acutely conscious of how naked the artist is when his work goes up for public display. In “Salon de 1857”, one of his comic lithographs for Le Charivari, a nude statue ignored amidst the top-hatted and pince-nezed onlookers who are all staring intently at the paintings on the walls, comes to life with a noiseless wail and contortion of her arms.

Daumier knew how it felt to be overlooked as an artist. This sympathy extended to players in the theatre and he created a whole series of pictures focused, not on the action on the stage, but on the restive audience determined to be entertained. In “What a frightful spectacle” (c. 1865) the attention is for once turned to the proscenium arch where a lone actor seems to be gripped in the throes of terrible stage fright. The toga thrown over his shoulder, bright red against the monochrome of the background, seems to symbolise the fresh blood of his dying career.

Daumier’s fascination with the art in performance and the often lonely predicament of the players, reached its extreme conclusion in a group of pictures depicting humble street performers – the lowest of the low in this profession. Musicians, strong men and clowns are all revealed unflinchingly but with a great deal of sympathy, Daumier combining his natural feeling for the marginalised with his personal experience of the artist’s life. Perhaps the two most memorable are “The Sideshow” (c.1865-66) and “Clown Playing a Drum” (c. 1865-67) in which the same drumming pierrot is shown in two different settings – the corner of a carnival and a busy street. In both he is being ignored, in both his set, sad face stares out at us as he beats the skins mechanically to an indifferent world. The clown, melancholy and tragic, but undeterred, became Daumier’s own alter-ego.

Detail from ‘The Sideshow (Parade de Saltimbanques)’, c. 1865-66.

The world, as the old saying goes, is a stage and Daumier, as the observing artist, sometimes its only audience. In the new form of mass transport – rail – he found another potent subject for the canvas. In another group of pictures showing the snapshot of lives as they passed from one place to another, Doumier typically dwelt in the cheapest cars. In perhaps the most famous of these, “The Third Class Railway Carriage” (1862-64) a gloomy compartment is peopled by a cross section of ordinary folk. Facing us in a row sits a young woman breast-feeding, an elderly matron clutching a basket on her knees and a small boy fast asleep beside her. Behind them bristle the heads of men in top hats, a brawny giant in a round-crowned slouch hat and another couple of women in head scarves, forming an entire panoply of the Parisian working and middling classes. No one talks, all are trapped in dour contemplation in the artificial confines of the carriage. It is as if Daumier was amongst them, sketch book in hand. Intriguingly though he never drew from life or employed models but, reticent to the last, transcribed directly from his memory and imagination back in the studio.

Daumier was a man of principles and passions who reserved his scorn for the hypocricy of the bourgeoisie and the callousness of the court and politics for his frequently blistering cartoons. In this he was fearless, even being jailed for a time for his outrageous depiction of King Louis-Philippe in “Gargantua” (1831). He came late to painting though and was always protective of it. It was as if he didn’t believe he had what it took to make it as a painter. Thus his painting was carried out in an atmosphere of experimentation, free from fashion and the censure of others. Some are astoundingly modern like the monumental series entitled “Man on a Rope” (1858-60). In others the seeds of Impressionism are clearly being sown, before even acknowledged fathers like Courbet and Manet.

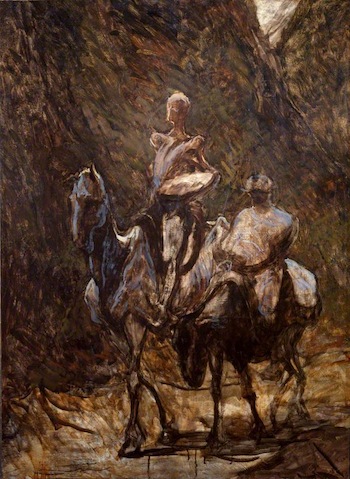

‘Don Quixote and Sancho Panza (Don Quichotte et Sancho Panza)’, c. 1870.

In his beautiful series inspired by “Don Quixote”, a book that he apparently always kept by his bed, many of Daumier’s preoccupations coalesce. In “Don Quixote and Sancho Panza” (c.1870) the eponymous hero and his sidekick ride along side by side in a landscape of trickling gloom, perhaps hinting at the blindness that would soon overtake the artist. It is no coincidence that the Don’s lance and upturned shield resemble paintbrush and palette respectively. Doumier clearly identified with his fictional friend and perhaps believed that the artist’s journey was also a grand delusion.

Many would disagree. In 1959 Francis Bacon said that it was “among the great paintings of the world.” An artist’s artist, Daumier was, and is, an artist for all men.

Daumier: Visions of Paris closes at the Royal Academy of Arts on 26th January 2014. For more information, including opening times and prices, visit the website.