“Give me a museum and I will fill it.” Pablo Picasso. The king is dead, long love the king! So Lucien Freud passes, and to whom does the mantle fall? Not many big-hitters left now; hopefully our heir apparent is not to be the craven Hodgekin, or the flatulent Gormley, and decidedly not those twin gaily-clad tricksters, Gilbert and George…eh, eh, who was that again, did somebody speak? Is there anybody out there left? Well yes, of course, Yorkshire’s favourite son, our David. The now domesticated owl in big glasses. Nemesis to the conceptualists and non-smokers amongst us, champion of the simple art of drawing and the complex art of the iPad, Mr Hockney of Bridlington, kindly take the stage!

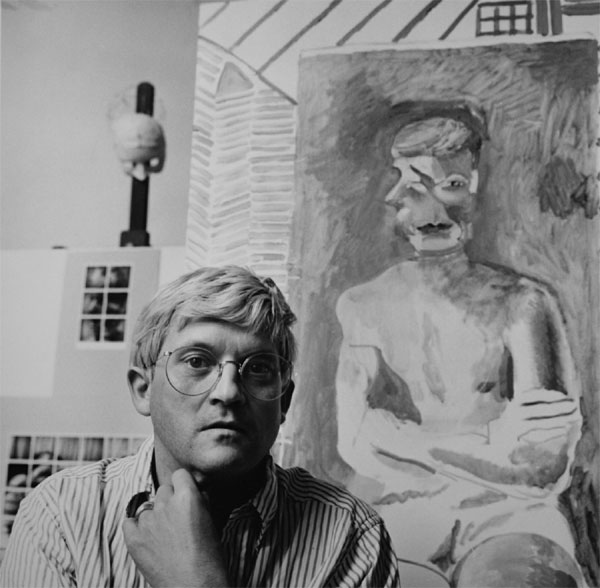

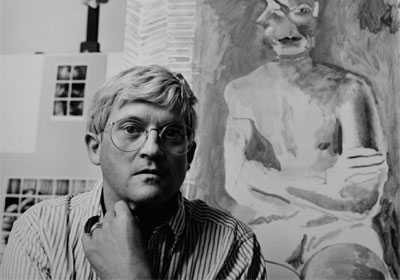

David Hockney by Paul Joyce, at Pembroke Studios, July 1982

And not just any old stage, but the entire footprint of The Royal Academy in London, which usually manages to mount at least three separate exhibitions simultaneously, or show over fifteen hundred indifferent pictures at its annual show. Now the entire space is given over to a living artist with a single-minded concept – to make us see the beauty in the decidedly ordinary, in details of a landscape you would usually hurry through with barely a glance to the right or left. But this is Yorkshire, the very loam which nurtured the young Hockney when he cycled these lanes as a lad, and then later as a conscientious objector tilling the soil. A landscape he learned to love and could never put behind him, not even when the fleshpots of Los Angeles sent their siren videos to him and lured him to a golden-skinned and pale- rumped heaven. Still, he made the yearly pilgrimage back home, first to visit his mother and then, after she died, to take over that very house he had bought for her and his sister, and turn it, as any good artist does, into a studio to work from. Baited, hooked, lined and sinkered, David was back with us and now we can all see the results.

The problem now (one of them at least) is that David has become a simulacrum of, and for, royalty. Curators, collectors, museum directors, fans and assorted hoi-polloi all prostrate themselves in his path. And I should know, as I have been there with him on countless occasions during the two decades I worked with him on a couple of books, and it is almost sickening how he is treated as virtually superhuman and with even some aspect of divinity.  Now, I am very happy to acknowledge that certain visionaries see the world in quite different ways to ourselves: Einstein, Heisenberg and Picasso for example. We can indeed traipse along in their majestic footsteps, hoping to sweep up some crumbs from their wake with a little illumination en route. But even Monet, a painter who has a greater facility than David with the application of oil paints, went unnoticed in St. Marks Square as pigeons added their own playful contributions to the vast accumulations of ciggie ash on his jacket. Who is that old fool with a fag jammed in his mouth and with a companion who looks like Mother Courage? Imagine Hockney outside the Doge’s Palace in the same scene? Look at the crowds! Call for the polizia!

Now, I am very happy to acknowledge that certain visionaries see the world in quite different ways to ourselves: Einstein, Heisenberg and Picasso for example. We can indeed traipse along in their majestic footsteps, hoping to sweep up some crumbs from their wake with a little illumination en route. But even Monet, a painter who has a greater facility than David with the application of oil paints, went unnoticed in St. Marks Square as pigeons added their own playful contributions to the vast accumulations of ciggie ash on his jacket. Who is that old fool with a fag jammed in his mouth and with a companion who looks like Mother Courage? Imagine Hockney outside the Doge’s Palace in the same scene? Look at the crowds! Call for the polizia!

This exhibition follows hard on the heels of the groundbreaking Leonardo at The National Gallery in London, and practically overnight has acquired the status of a blockbusting ‘must see’, and although by no means uniting the critics, has generally been well-received by them. However it has had the effect of bringing out the worst in some (Brian Sewell) and the best in others (Waldemar Januszczak).

“….the intense autumn glows he records on the floor of the forest, and the cool summer greens of the leaves in the trees, feel strikingly authentic, and uplifting. Great landscape art has always delivered more than mere depiction, and in these austere views Hockney captures not just the look of the landscape, but its impact on the spirit.” Jannuszczak

“As no one who knows anything of Yorkshire’s wolds has ever seen them clad in the ghastly gaudiness of Hockney’s vision, I must ask, if he is not purblind, from whom he borrows this jangling, jarring, grating palette?…he is surrounded by sycophants, none of whom has the honesty to tell him what he needs to know – that he has fallen far from the saturated brilliance of his last brief fling with quality, the Grand Canyon drawings and paintings of 1998…Indeed, half these pictures are fit only for the railings of Green Park, across the way from the Royal Academy, and would never be accepted for the Summer Exhibition were they sent in under pseudonyms.” Sewell

The show occupies all eleven of the Royal Academy’s main galleries, an unprecedented degree of access never previously accorded to an artist, living or dead. This, therefore, is a totally immersive experience, the closest one will ever be to sharing the imagination and to a certain extent to be actually inside the head of one single person. But, as in a dream, things that seem recognisable to begin with, gradually transmogrify into alternate realities. In a curious way this exhibition simultaneously overwhelms, whilst at the same time under-delivers.

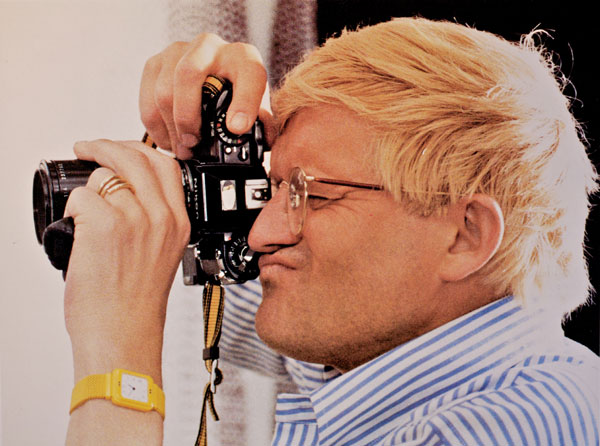

Hockney at his Hollywood studio, mid-80s (c) Paul Joyce

The first octagonal gallery has a series of four giant canvasses of trees in Thixendale, each one marking a season and it is here that one gathers a little what is ahead for the viewer: size, space, intense colour and frequently extreme lack of detail. In short, a somewhat uneasy alliance between early Monet and late Picasso. However, there is no mistaking the fact that one is in the landscape, part of it, sharing it (and here the experience of being in a gallery with many people brings the excitement of something participated in, as one does sometime feel in a theatre or cinema).

Next, a smaller space is given over to David’s early work including Flight into Italy: That’s Switzerland That Was, a wonderfully inventive ‘pop art’ style depiction of Hockney’s first journey abroad, crossing Switzerland in a windowless Morris Minor van which he was unable to see out of. (Afterwards he bought a postcard of the landscape he had missed, and painted the background from that.) Also in these early rooms appear the wonderful Grand Canyon pieces whose colour is really going to test these later Yorkshire landscapes, soon to be seen in the adjoining rooms. Boldly too, paintings from Hockney’s early student years, showing the dull influence of those such as William Coldstream, academic, dun coloured and amateur they hold little hint of what was to emerge, and emerge very quickly. But side by side with these dour couple of Yorkshire urban scenes is another wonderful early example from 1965 of David’s singularly youthful vision Rocky Mountains and Tired Indians. As a slight digression: when I was making a film on Hockney’s photographic work, we visited Salt’s Mill which houses a large Hockney archive, including some early works. There quite surprisingly is a female nude on a large horizontal canvas and as we came to film it, clearly marked on its reverse side –and not usually seen – in bold letters in David’s own hand was ‘For sale: £2-10s’ (£2.50 post decimalisation). I immediately offered Robin Silver (owner of Salt’s Mill) £2.50 which he sadly refused; in auction this piece would probably be worth £5-10 million.

David Hockney, Nichols Canyon, 1980 Acrylic on canvas 213.4 x 152.4 cm Private collection © David Hockney

Moving on, we encounter his (at that point) largest-ever canvas of Mulholland Drive where Hockney fuses his love of the natural world (remember that Los Angeles is built on a living landscape – albeit a desert) with his graphic concerns by making the backdrop – which in purely naturalistic terms should have been blue sky – a street map grid of the cities’ northern regions. Here, once again, Hockney’s visionary genius emerges brightly shining into the light, soon to be submerged beneath the waves of countless incoming projects.

Now, in the adjoining gallery, we encounter Hockney’s early (in Yorkshire terms, the 90s) attempts at depicting the landscape he knows well but has not painted for decades, one’s done at the behest of his terminally ill friend, Jonathan Silver. Silver acquired and developed Salt’s Mill as an arts centre near Bradford, but was unable to see the project through to completion as a virulent form of pancreatic cancer took him from us very quickly. He and David were very close, and Hockney was devastated by this loss, but before he died Jonathan convinced David to start painting the Yorkshire landscape (including a marvellous large painting on two canvasses – a study of Salt’s Mill itself). Superficially these works seem out of place, too garish or (being kinder) colourful. But here you see Hockney was bringing an LA sensibility to bear on an English subject, and almost inevitably one element at least of the equation would suffer as a result.

Following on from the oil landscapes of the Yorkshire Wolds and surroundings prompted by Jonathan Silver, David picked up his watercolours for a series which became the (until then) most considered series about his home county he had yet attempted. This seems to me a case where the palette and the subject are perfectly well suited. The flat, damp landscape responds beautifully when represented in this medium and with such subtlety of colour and expression. Grey puddles hint at reflected shades of virtually hidden colours in a landscape which is immediately recognisable, familiar, domestic and non-threatening. However, this eloquent series to which the RA donates another room, is merely the lull before a stormy continuance of the intense Yorkshire colours, which we have to assume that Hockney regards as being representational of the ‘truth’ laid out before him.

David Hockney, The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011. Oil on 32 canvases (each 91.4 x 121.9 cm), 365.8 x 975.4 cm; one of a 52-part work. Photo credit: Jonathan Wilkinson

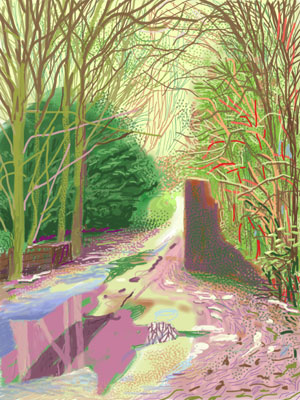

Arriving at the vast central gallery, David gives the whole space to Woldgate Woods and what many would consider to be his crowning achievement, multiple canvasses covering a single wall and devoted to a single theme: The Arrival of Spring. I think this is the one work which, within it, condenses all my reservations about David’s current vision, for it has nothing of the impact of his earlier wood studies on multiple canvasses. Rather it is like a giant stage design for an opera yet to be composed, but one which would, if representational of the vast image, be both child-like and sentimental. Unfortunately its presence dominates the central arena, but if you can literally put it behind you for a moment and walk forward into the gallery itself, then riches await you in the very same space: a series of quite beautifully realised large prints composed by, and printed from, David’s iPad.

For years I had been not just ignoring but actively dismissing Hockney’s embracing of new Apple technology, and now I realise how mistaken I have been. For this work is truly spectacular, confounding all expectations of what can be done with a finger or stylus on a pocket-sized unyielding glass screen. One would think that the subtleties at work when oil paint, brush and canvas conjoin would be difficult to replicate, let alone exceed with a flat screen and a £15 software programme (Brushes). However, where the lack of detail in many of the oil studies both disturbs and off-puts, here all is quite beautifully rendered with gradations of texture and colour, which even Monet would have had great difficulty in achieving. If there is a single revelation within this show, then the iPad work is it.

David Hockney by Paul Joyce

Regarding David’s experimentation with high-definition multi-camera recordings, here I must declare an interest, for it was on the basis of his early experimentation with 16mm for an 80s South Bank Show experimental film and photography that we met in July 1982, from which our friendship has grown over the intervening years. It was clear to me then, over 30 years ago, having walked into Kasmin’s gallery in Cork Street to see David’s display of Polaroid ‘joiners’, that he was beginning to use photography in a way that it had never been so ambitiously attempted before. At a stroke he had shattered conventional one-point perspective and begun to represent (as opposed to visualise) the world and its contents as if seen from the viewpoint of a moving creature with binocular vision (yes, like us – human beings!). So he single-handedly began what I still believe to be the biggest experiment in the development of photography over its span of over 150 years.

When we were working on our first book (Hockney on Photography, Jonathan Cape, 1988), I tried to persuade him to shift his attention from still photography to moving images, but he was always reluctant to take this step in a serious manner. Perhaps the fact that he was living in Hollywood, home of moving pictures, was a contributory as well as proscribing factor, or that he felt he would need to ask for technical assistance and so yield some authority to another artistic or technical sensibility. So it has taken him some 30 years to come back to the moving image, and maybe (and advisedly) he was waiting for digital technology to come to his aid.

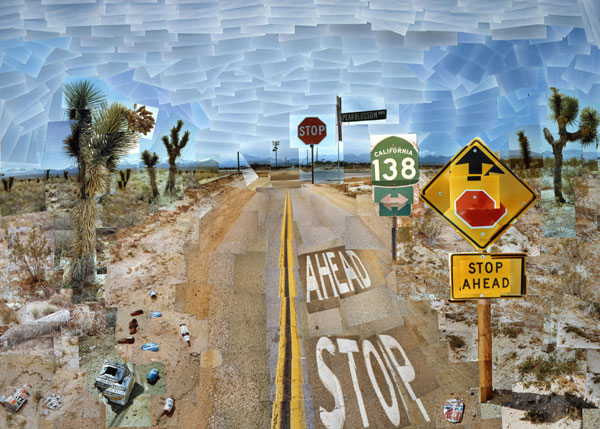

David Hockney, Pearblossom Highway, 11-18 April 1986. Photographic collage 119.4 x 163.8 cm. Held by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

And this is precisely what it does. Usually nine but occasionally up to eighteen cameras are locked onto a frame attached to the side or front of his Land Rover which drives slowly (about 5mph) through the landscape during different seasons, recording images simultaneously in time whilst ever so slightly abutting one another. The result is a hypnotic series of views where one’s vision scans the ever-changing landscape with a level of detail which even our own eyes would fail to register, assuming we were to undertake such a rigorous journey (within the real landscape, that is). Here it could well be that doubts about the Yorkshire Wolds as a suitable subject for close scrutiny are, for many viewers, laid to rest.

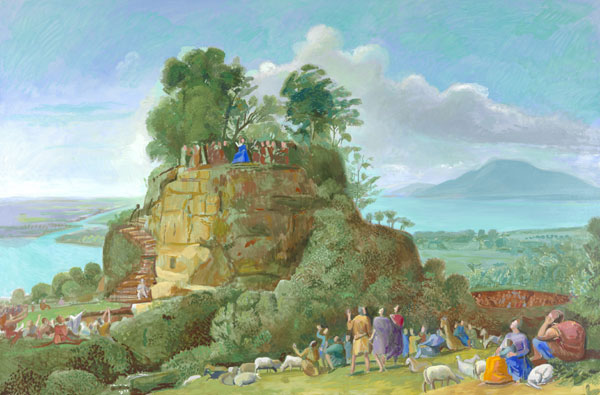

One glaring lapse of judgement, that one might almost call aberration in an otherwise overwhelming show, is the room devoted to Hockney’s attempts to ‘reconstitute’ a magical landscape by Claude Lorrain, The Sermon on the Mount, which he spotted some little while ago in the Frick collection in New York. In a series of (in my opinion) misjudged attempts to ‘clean and refresh’ the original colour, David goes from bad to worse as he plunges on, aided by the latest digital technology, which in this case apparently lets him down, or at the very least fails to complement Lorrain’s vision to a mindboggling degree. Surely a classic case of advice – any advice at all- failing to come to his aid and abort the process before it becomes a matter for public display. I would suggest a rapid movement through this room with increasing speed and blinkers strapped firmly in place…

David Hockney, The Sermon on the Mount II (After Claude), 2010 Oil on canvas 171.5 x 259.7 cm. Photo credit: Richard Schmidt

Large prints of Yosemite, again courtesy of the iPad, dominate the final room and hint at the possibility, the beginning, of another series, hopefully of grander and maybe even more ‘sublime’ New World landscapes? These are truly wonderful images, manipulated by the latest printing technology to almost ten feet in height. Preserve some measure of concentration, please do, for this last, and in many respects, best room of all.

So, gradually we behold that one by one the great fall off the perch, leaving, if not by default then at least by exigency, David Hockney, Britain’s greatest living artist. But wait a moment, hasn’t he tacitly and quietly acknowledged this accolade on past occasions? In his late twenties and early thirties with A Bigger Splash; in his forties, Mr and Mrs Clarke and Percy, together with his great ground-breaking photographic joiners; in his fifties with Pearblossom Highway; in his sixties with The Grand Canyon Suite, magnificent double portraits and his Camera Lucida drawing experiments? Indeed, even Brian Sewell’s eviscerating review for The Standard states quite clearly that Sewell thought of Hockney as our greatest draftsman for many years in the 70s and 80s, a sentiment with which I absolutely concur.

David Hockney, The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011. iPad drawing printed on paper 144.1 x 108 cm; one of a 52-part work.

Actually, therefore, hasn’t David always been our best and brightest? Of course he has, so we should not see this great show in any way as being valedictory. In fact, I think the hints are all there of greatness yet to come, especially in the last room full of those new Yosemite images. In this vast and hugely impressive exhibition, David has connected with the soil which nourished him, and soon, mark my words, the old restlessness will kick in again for new horizons and more challenging landscapes. He has shown us, after all is said and done, that a great artist can make anything interesting, even the apparently featureless topography of the artistically abandoned Yorkshire Wolds. He has, magician and alchemist-like, turned the humble and ordinary into things full of wonder that can withstand endless contemplation. If this is not enough to send him to the top of the class, frankly I can think of nothing else which might.

On the question of size, of scale, we followed David willingly to the very edge of the largest hole in the world, the Grand Canyon, and stood there in dizzying disbelief (I saw one spectator at The Pompidou Centre in Paris in 1999 actually fall over in front of the multiple canvasses, gripped by an attack of vertigo). But here subject matter and execution conjoined in an entirely natural way and one which was surely appropriate to the subject (Frederick Church and Thomas Moran had of course been there before him in many similar respects). However, with the Yorkshire Wolds I wonder if the sheer scale of execution is an attempt to stamp upon these humble lanes and fields a mythological significance where, if it does indeed exist, is not contingent on sheer size. The world, after all, as Blake so resonantly reminds us, can reside in a grain of sand.

And in relation to this last point, musing on the matter of scale, there is just one more observation I feel I must make, and I really hope it is not at the expense of his friendship which I cherish: a caveat, one might say.

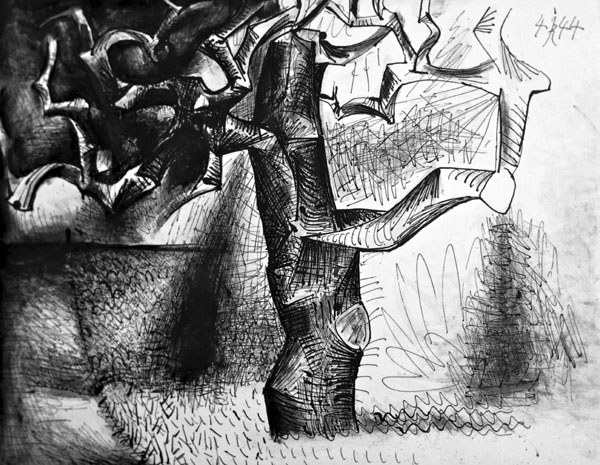

A couple of years ago, in a Paris bookshop not far from the Seineside location of Shakespeare and Co, I happened on a modest publication simply entitled Arbres. As a landscape artist and photographer fascinated by trees and their depiction, I would have bought it sight unseen – in fact like any familiar internet purchase. But I thumbed through it, and there, towards the end and without any trumpeting or pomp, was a modest line drawing of a diminutive tree by Pablo Picasso. In the midst of examples by Rembrandt, Rubens, Monet, van Gogh and other luminaries, rested this quietly evoked stealth bomber of an image. And the more I gazed upon this apparently humble depiction, the more it spoke to me.

A sketch of a tree, by Pablo Picasso

For what Picasso does in this drawing, which on a good day would probably take him no more than half an hour to execute, is to even go beyond what Hockney would call the essence of “treeness” into another territory altogether. The surface is penetrated, like the mirrors of mercury in a Jean Cocteau film, and we find ourselves in a landscape which is, like Coucteau’s, both familiar and alien. Picasso’s tree is always a tree, but it bears other recognisable markings too – wounds and primitive armour for example – totemic messages which make an apparently simple sketch a statement about the struggle of every living thing both for a place in the universe, and beyond that a need to survive at all costs. In this respect, Picasso outdoes even anthropomorphism. His tree is not something ‘out there’ to be simply gazed at, admired, even pitied, but something to do directly with us, ourselves. In my opinion, this constitutes truly great art.

Now, at the end of these personal musings, I leave it to you individually to ask yourselves if anyone, even our own and dearest son David Hockney, can indeed take their place beside the short, bald and uniquely gifted Spanish magician who could fill any museum in the world, over and over and over again.

David Hockney: A Bigger Picture shows at The Royal Academy until 9th April. For more information and to purchase tickets, visit the website.

Paul Joyce is working on a series of paintings of Venice, to be shown at a new West End gallery early next year. His work as a photographer and artist is held in numerous public and private collections worldwide, and his company Lucida Productions is responsible for making over 40 arts-related films during the past three decades.

1 Comment

Hockney is no Picasso. His early abstract works are probably his most interesting but those later empty Californian paintings give ennui a bad name. They seem so lifeless, as if they’ve been executed by an architect.

Britain is home to some wonderful female painters and sculptors who deserve celebrating.